What went so wrong with covid in India? Everything.

But voices like his were drowned out by the federal government’s messaging, which suggested that India had somehow outwitted the virus. The hype was so strong that even some medical professionals bought into it. A Harvard Medical School professor told the financial daily Mint that “the pandemic has behaved in a very unique way in India.”

“The real harm in undercounting is that people will take the pandemic lightly,” says Arun. “If supposedly few people are dying due to covid, the public will think it doesn’t kill, and they won’t change their behavior.” In fact, by mid-December India had reached yet another somber milestone: it recorded its 10 millionth infection. It was only the second country to do so, after the US.

The government hadn’t used the first lockdown wisely, but December was its chance to set things right, says Gagandeep Kang, a professor of microbiology at the Christian Medical College in Vellore, Tamil Nadu. She says that a number of tactics—ramping up sequencing, studying public behavior, collecting more data, refusing permission for superspreader events, and starting the vaccine rollout earlier than planned—would have saved many lives during the now-inevitable second wave.

Instead, she says, the government continued its “top-down approach,” in which bureaucrats rather than scientists and health-care professionals were making decisions.

“We live in a very unequal society,” she says. “So we need to engage people and build partnerships at a granular level if we are to effectively deliver information and resources.”

In December the government of Goa let its guard down entirely. The state is heavily reliant on tourism, which makes up nearly 17% of its income. The bulk of the tourists show up in December to celebrate Christmas and New Year on sandy beaches with raves and fireworks.

Vivek Menezes, a Goan journalist, says that the state’s reputation as “the place to be” had not faded during the pandemic. “It’s the place for India’s wealthy and for Bollywood, and therefore it’s the place for India,” Menezes says. The pandemic had kept foreign tourists from visiting, but domestic holidaymakers poured in. Some states, such as Maharashtra, had placed restrictions at their borders; others, like Kerala, had a strict policy of contact tracing. In Goa, visitors didn’t even have to show a negative covid test. And the state’s masking policy extended only to health-care workers, visitors to health-care facilities, and people showing symptoms. “Goa was left to the dogs,” says Menezes.

The world’s largest superspreader

India started 2021 having registered nearly 150,000 deaths. Only then, in January, did the government place its first vaccine order, and it was for a shockingly low amount—just 11 million doses of Covishield, the Indian version of the AstraZeneca vaccine. It also ordered 5.5 million doses of Covaxin, a locally developed vaccine that has yet to publish efficacy data. Those orders fell far short of what the country actually needed. Subhash Salunke, a senior advisor to the independent Public Health Foundation of India, estimates that 1.4 billion doses would have been required to fully vaccinate all eligible adults.

On January 28, in an address to the World Economic Forum in Davos, Modi declared that India had “saved humanity from a big disaster by containing corona effectively.” His government then gave the go-ahead for the Kumbh Mela, a Hindu festival that attracts crushing throngs of millions of people to the holy city of Haridwar in the northern state of Uttarakhand, which is famous for its temples and pilgrimage sites. When the state’s former chief minister suggested that the festival should be “symbolic” this year given the circumstances, he was fired.

A senior politician in the prime minister’s Bharatiya Janata Party told the Indian magazine The Caravan that the federal government had its eye on the forthcoming state elections and didn’t want to lose the support of religious leaders. As it turned out, the Kumbh wasn’t just any superspreader event—with a reported 9.1 million people in attendance, it was the world’s largest superspreader event. “Any person with a basic textbook on public health would have told you this was not the time,” says Kang.

The Indian government only placed its first vaccine order in January 2021, after having registered nearly 150,000 deaths. Even then, it was for a shockingly low amount—11 million doses of Covishield and 5.5 million doses of Covaxin for a country of 1.3 billion.

In February Salunke, the public health expert, was working in an agrarian district in the western state of Maharashtra when he noticed that the virus was transmitting “much faster” than before. It was affecting entire families.

“I felt we were dealing with an agent that had changed or appeared to have changed,” he says. “I started to investigate.” Salunke, it now turns out, had found one mutation of a variant that had been detected in India the previous October. He suspected that the variant, now known as delta, was about to run rampant. It did. It is now in more than 90 countries.

“I went to all those who are responsible and those who matter—whether district level officials or bureaucrats at the central level, you name it. Everyone who I knew I immediately shared this information with,” he says.

Salunke’s discovery doesn’t appear to have affected the official response. Even as the second wave was accelerating and after the WHO designated the new mutation “a variant of interest” on April 4, Modi kept up his hectic schedule ahead of state elections in West Bengal, personally appearing at numerous public rallies.

At one point he gloated about the size of the crowd he had attracted: “In all directions I see huge crowds of people … I have never seen such crowds at a rally.”

“The rallies were a direct message from the leadership that the virus was gone,” says Laxminarayan of the Center for Disease Dynamics, Economics & Policy.

The second wave filled hospitals, which quickly ran out of beds, oxygen, and medication, forcing gasping patients to wait—and then die—in homes, in parking lots, and on sidewalks. Crematoriums had to build makeshift pyres to keep up with the demand, and there were reports that the outpouring of ash drifted so far it stained clothes a kilometer away. Many poor people couldn’t even afford to pay for funeral rites and immersed the bodies of their loved ones directly into the River Ganges, which led hundreds of corpses to wash up on the banks in several states. Alongside these apocalyptic scenes came the news that deadly fungal infections were overwhelming covid patients, likely as a result of lower infection control and overreliance on steroids in treating the virus.

Chaos continues; Delta spreads

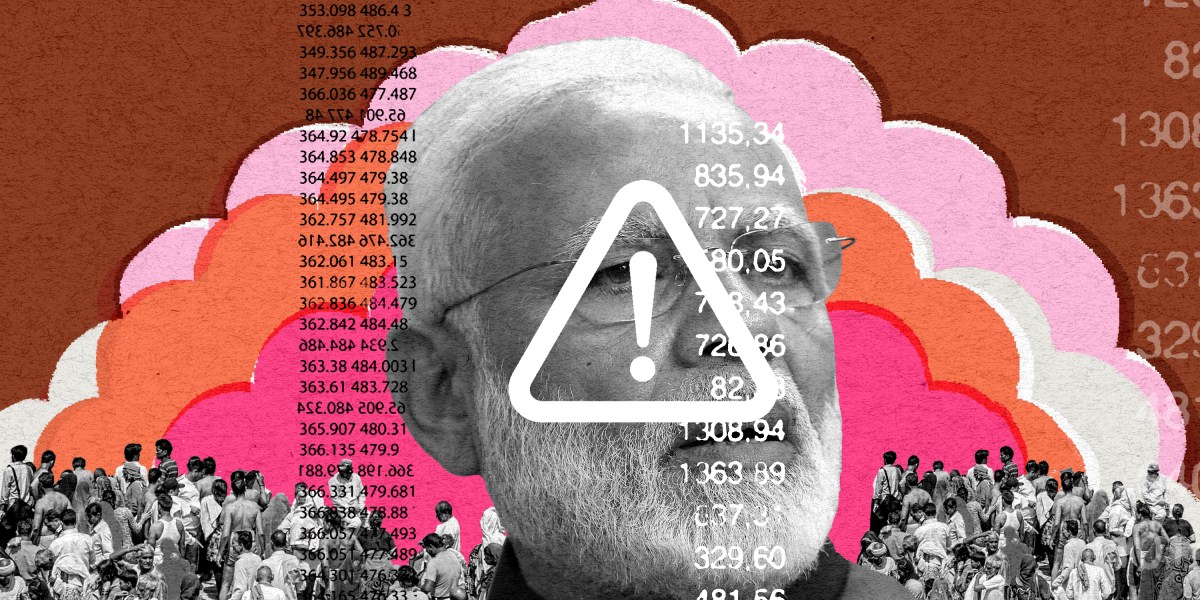

And all along, there has been Modi. The prime minister had been the face of India’s fight against the pandemic—literally: his headshot appears prominently on the certificate given to people who get their vaccine. But after the second wave, his premature triumphalism was mocked and his lack of preparedness derided widely. Since then, he has gone largely missing from the public eye, leaving it to colleagues to place the blame elsewhere, most notably—and inaccurately—on the government’s political opposition. As a result, Indians have been left to face the biggest national crisis of their lifetime on their own.

This abandonment has created a sense of camaraderie among some groups of Indians, with many using social media and WhatsApp to help each other out by sharing information about hospital beds and oxygen cylinders. They have also organized on the ground, distributing meals to those in need.

“The [BJP] rallies were a direct message from the leadership that the virus was gone.”

Ramanan Laxminarayan, the Center for Disease Dynamics, Economics & Policy

But the leadership vacuum has also produced a huge market for profiteers and scammers at the highest levels. In May, opposition politicians accused a leader of the ruling BJP party, Tejaswi Surya, of taking part in a vaccine commission scam. And the health minister of Goa, Vishwajit Rane, was forced to deny claims that he played a part in a scam involving the purchase of ventilators. Even the prime minister’s signature covid relief fund, PM Cares, came under fire after it spent Rs 2,250 crore (over $300 million) on 60,000 ventilators that doctors later complained were faulty and “too risky to use.” The fund, which attracted at least $423 million in donations, has also raised concerns about corruption and lack of transparency.

A successful vaccination agenda might have helped erase the memory of the string of missteps, but under Modi it has only been one technocratic mistake after another. At the end of May, with far fewer vaccines in hand than it needs, the government announced plans to start mixing doses of different vaccine types. And at the height of the second wave, it introduced Co-WIN, an online booking system that was mandatory for anyone under 45 who was trying to get vaccinated. The system, which had been under scrutiny for months, was disastrous: not only did it automatically exclude those who do not use computers and smartphones, but it was also hit by bugs and overwhelmed by people desperate to get protection.