What If Schools Nurtured Imagination?

Imagination is central to empathy, to creating better lives, to envisioning and then enacting a positive future. Yet imagination is also demonstrably in decline at precisely the moment when we need it most. In his book, author Rob Hopkins asks why imagination is in decline, and what we must do to revive and reclaim it. Once we do, there is no end to what we might accomplish.

The following is an excerpt from From What Is to What If by Rob Hopkins. It has been adapted for the web.

Imagine for a moment – and give yourself some time, because this might require a fair amount of imagining – that you left school around age eighteen, or twenty-two, or whenever, feeling alive, empowered and excited for the future, as you set off with a spring in your step, eager to build your life and rebuild the world. Imagine you felt no fear in your young mind about how you would make your way in the world, find your place, support yourself, and have a good life according to your own definition and values. Imagine that your sense of imagination felt more vibrant and dynamic than it did when you were a child, not relegated to your past at all, but honoured and honed almost to a superpower, so that you were ready to call on it for every decision you needed to make.

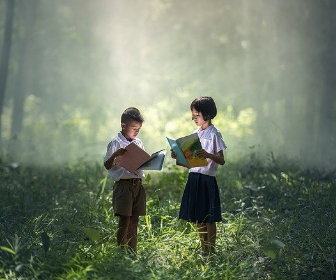

Imagine that you loved your education and felt blessed and grateful to have it, something of real value, unique to you, that nobody could ever take away. Imagine that it involved grappling with questions that mattered to you and solving problems that felt relevant, to which no single solution existed? Imagine that you learned the people’s history and that it helped you find common ground with others, so that you felt you could go anywhere and do anything and enjoy a convivial meal in friendship and good cheer with anyone. What if it included lying in the grass beneath majestic trees, gazing up into their cathedral canopies, overcome with a sense of awe and connection to all living things? Imagine that going to school was replete with moments that felt as though they were bursting with possibility.

Imagine that you loved your education and felt blessed and grateful to have it, something of real value, unique to you, that nobody could ever take away. Imagine that it involved grappling with questions that mattered to you and solving problems that felt relevant, to which no single solution existed? Imagine that you learned the people’s history and that it helped you find common ground with others, so that you felt you could go anywhere and do anything and enjoy a convivial meal in friendship and good cheer with anyone. What if it included lying in the grass beneath majestic trees, gazing up into their cathedral canopies, overcome with a sense of awe and connection to all living things? Imagine that going to school was replete with moments that felt as though they were bursting with possibility.

What if you spent time at the feet of storytellers, rappers, musicians, craftspeople and elders, learning from their examples? What if you had time to daydream, to stare out of the window, to dip your fingers into a glittering stream as it drifted past? What if you spent long hours with your hands and face covered in paint, clay, charcoal powder and ink? If you had ample time and space to play, to bring entire worlds into being because you played them into existence? What if your education included laughter? Lots of laughter. And taught you how to be independent, to manage money competently, to budget and live within limits? What if it gave you time with animals, watching them, feeding them, learning their songs? And gave you hands that were skilled, comfortable with tools, so that you could easily think of yourself as a maker, and actually be one?

I don’t know about you, but my schooling didn’t look much like this. Or anything like it. And in the thirty-odd years since I left school, it has, in most places at least, only accelerated its retreat.

It seems as though, until school begins, children’s imaginations are pretty consistently healthy. Marjorie Taylor, a professor of psychology at the University of Oregon, has spent many years researching the development of imagination and creativity, in particular studying the phenomenon of ‘imaginary friends’.1 In her ‘Imagination Lab’, she particularly focuses on the imaginative abilities of three-to-five-year-olds. ‘I haven’t seen any decline at all in all the years that I’ve been interviewing children,’ she told me.2 Her work reveals the dazzlingly inventive imaginative worlds inhabited by young children. But then, it seems, something happens once kids reach school that not only devalues those worlds but actively undermines them.

Case in point: Thomas Deacon Academy in Peterborough opened in 2007 at a cost of £46.4m, the most expensive new state school in the United Kingdom. But it was built with no playground. Nowhere to play. Alan McMurdo, head of this new ‘super school’, told the BBC that ‘youngsters can play in their own time, play in their local communities. What I want from my teachers is maximum teaching and I want maximum learning from the youngsters.’3

High school students in Texas currently spend up to 45 days in their 180-day school year taking tests, and those in grades three to eight spend between 19 and 27 days. One school superintendent said, ‘When do we put a stick in a wheel and say, that’s enough, stop? Because we are going to spend the next 10 years trying to slow that wheel down, and we’ve got 10 years of kids that are suffering.’4 Meanwhile, a 2017 report in The Times quoted a secondary teacher in the United Kingdom bemoaning the fact that her Year 7 intake, straight from primary school, were unable to tell a story. ‘They knew what a fronted adverbial noun was,’ she said, ‘and how to spot an internal clause, and even what a preposition was – but when I set them a task to write a story, they broke down and cried.’5

High school students in Texas currently spend up to 45 days in their 180-day school year taking tests, and those in grades three to eight spend between 19 and 27 days. One school superintendent said, ‘When do we put a stick in a wheel and say, that’s enough, stop? Because we are going to spend the next 10 years trying to slow that wheel down, and we’ve got 10 years of kids that are suffering.’4 Meanwhile, a 2017 report in The Times quoted a secondary teacher in the United Kingdom bemoaning the fact that her Year 7 intake, straight from primary school, were unable to tell a story. ‘They knew what a fronted adverbial noun was,’ she said, ‘and how to spot an internal clause, and even what a preposition was – but when I set them a task to write a story, they broke down and cried.’5

Eleven-year-olds unable to make up stories? Something’s not right here. Eric Liu and Scott Noppe-Brandon, in their book Imagination First, write: ‘It is pretty clear what makes young humans allergic to imagination: school.’6

What if we could do better by the next generation? What if school were an enlivening and empowering experience for them? What if they felt no fear that they were about to get the answers to these big questions wrong (because they’d internalised that there’s only one right answer, one way to be in the world, one path to follow)? What if young people felt an unshakeable belief that anything were possible and that they could achieve whatever they felt capable of in that moment when they set off into the world? What would be their first move? And the next? What kind of life would they build? What if we all felt this way? What would society look like?

Notes

- Henry Porter,‘To Be Alone in the Dawn Chorus Reminds Us How Precious Life Is’, Guardian, 4 May 2013, https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2013/may /04/dawn-chorus-thing-of-beauty.

- What’s a ‘wildlife disco’? Have a look at http://www.soundartradio.org.uk/services /projects/wildlife-disco/.

- Rob Hopkins, ‘“You Only Get So Many Mays in Your Life”: Why Our Imagination Needs the Dawn Chorus’, Imagination Taking Power (blog), 10 May 2017, https:// www.robhopkins.net/2017/05/10/204/.

- Hank Johnston, ‘A Camping Trip with Roosevelt and Muir’, Yosemite 56, no. 3 (1994): 2–4.

- Sierra Club, Theodore Roosevelt 1858–1919, Sierra Club, The John Muir Exhibit, https://vault.sierraclub.org/john_muir_exhibit/people/roosevelt.aspx.

- Johnston, ‘A Camping Trip’.