Want To Study The Sky? Astronomers Release Huge Data Set To The Public

The Victor Blanco telescope is a 4-meter wide telescope located at the Cerro Tololo Inter-American … [+]

(Fermilab/Reidar Hahn)

In 1998, two groups of astronomers discovered that the most distant objects in the universe are moving away from Earth faster than the leading theory of cosmology could describe. This observation led to the realization that the universe was permeated by a repulsive form of gravity called dark energy that was pushing the universe apart. Since this observation, several large groups of astronomers were formed to better understand this interesting phenomenon. One of them, called the Dark Energy Survey (DES), has recently publicly released an enormous amount of data for anyone to exploit. This data set contains over seven hundred million individual astronomical objects.

Experiments designed to study dark energy involve huge telescopes, able to see galaxies and supernovae billions of light years away. Since the speed of light is finite, seeing objects that far away means looking back in time, simply because it takes light that long to travel that distance. This technique means that by looking at more and more distant galaxies, you can see what the universe was doing for much of its fourteen billion year lifetime.

Furthermore, by looking at the spectrum of each galaxy, you can determine how fast it is moving away from Earth. Objects moving away from us appear redder than they would if they were stationary and, the faster they move, the redder they appear. The expansion of the universe due to the Big Bang further reddens these distant and ancient galaxies.

By correlating the speed of individual galaxies with their distance, scientists can work out how the expansion of the universe has changed over time. What they’ve found is that the universe was slowing down for the first nine billion years of its life; then, about five billion years ago, it began to speed up.

This accelerating expansion is driven by an energy field that astronomers call dark energy. The data suggests that dark energy is a constant energy density, which is called the cosmological constant. However, it remains possible that dark energy could be changing – either increasing or decreasing – and the change would have very significant consequences on the future of the cosmos. Trying to resolve whether dark energy is constant or changing is the primary reason that the DES program began.

MORE FOR YOU

Inside the dome of the Victor Blanco telescope located in Chile. This facility is used to study … [+]

REIDAR HAHN

DES uses a camera on a telescope located high atop a mountain in Chile. It began serious operations in August 2013, and it observed the heavens about 100 days each year, studying a 5,000 square degree swath of the sky in the southern hemisphere. It ceased operations in January 2019, having observed the sky for 758 nights over its six years of operations. (Disclosure: The DES camera (e.g. DECam) was built at Fermilab by an international collaboration of scientists, engineers, and technical professionals. I am a scientist at Fermilab, although I am not involved with the DES research program.)

DES released a large set of data (released in 2018 and called data set 1), which encompassed data recorded between August 2013 and February 2016. The recent release (released in January 2021 and called data set 2) represents the entire six year data set. A release of data that covers an even larger fraction of the sky is expected to be released relatively soon.

The new release is a veritable treasure trove of information for scientists and science enthusiasts to exploit. The original data set has resulted in hundreds of scientific publications, both by DES collaborators and by people who have independently mined the data. While the main goal of DES is to explain the expansion history of the universe, it also is able to study distortions of the shape of distant galaxies to determine an accurate map of the dark matter in the universe. It also has been used to survey the location of galaxies at all distances to understand the way in which they are distributed. Astronomers know that on the largest distance scales, galaxies are distributed uniformly. However, on distance scales of hundreds of millions of light years, galaxies are distributed unevenly – much like the foam on a mug of root beer seems uniform, but when looked at more closely, is an array of bubbles. This frothy, bubbly, structure, of the universe is a fossil remnant of sound waves that existed in universe, shortly after it began.

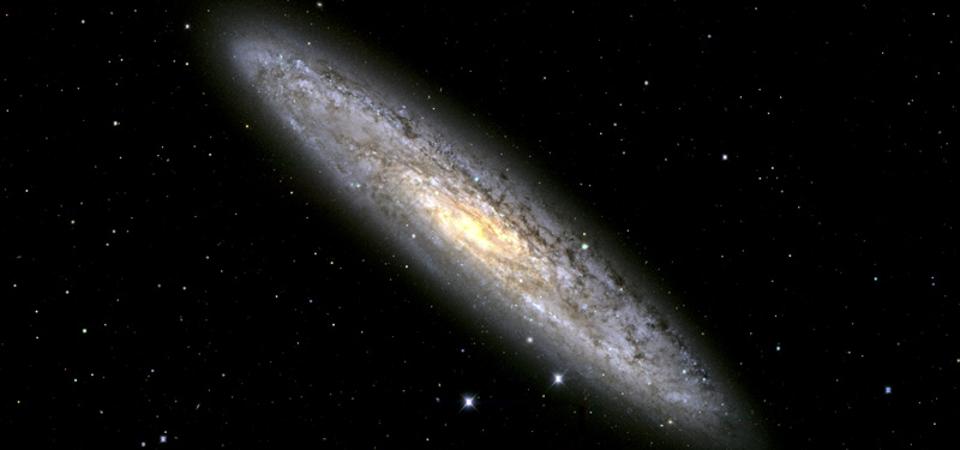

NGC-253 (e. g. the Sculptor Galaxy or Silver Dollar Galaxy), photographed by the Dark Energy Survey … [+]

DES Collaboration

Although the leading scientific goal of DES is to study distant galaxies, the data is more versatile than that. Astronomers have used it to find dwarf galaxies orbiting the Milky Way. It has been used to discover minor planets within the solar system, but outside the orbit of Neptune. It has been used to study gravitational waves. And studying the characteristics of distant supernovae is also part of its observational program.

All DES data will be made available to the public. If you have an interesting idea about some astronomical conundrum, and the camera on the Dark Energy Survey has collected data appropriate for the study you are interested in, the recently released data is available for you to use. Using the data requires commitment, but, quite literally, the sky’s the limit.