This is how America gets its vaccines

Biden’s newly released pandemic strategy is organized around a central goal: to oversee administration of 100 million vaccines in 100 days. To do it, he’ll have to fix the mess.

Some critics have called his plan too ambitious; others have said it’s not ambitious enough. It’s guaranteed to be an uphill battle. But before we get to the solutions, we need to understand how the system operates at the moment—and which aspects of it should be ditched, replaced, or retained.

From manufacturer to patient

At the federal level, two core systems sit between the vaccine factories and the clinics that will administer the shots: Tiberius, the Department of Health and Human Services’ vaccine allocation planning system, and VTrckS, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s vaccine ordering portal.

Tiberius takes data from dozens of mismatched sources and turns it into usable information to help state and federal agencies plan distribution. VTrckS is where states actually order and distribute shots.

The two are eons apart technologically. Whereas Palantir built Tiberius last summer using the latest available technology, VTrckS is a legacy system that has passed through multiple vendors over its 10-year existence. The two are largely tied together by people downloading files from one and uploading them to the other.

Dozens of other private, local, state, and federal systems are involved in allocating, distributing, tracking, and administering vaccines. Here’s a step-by-step explanation of the process.

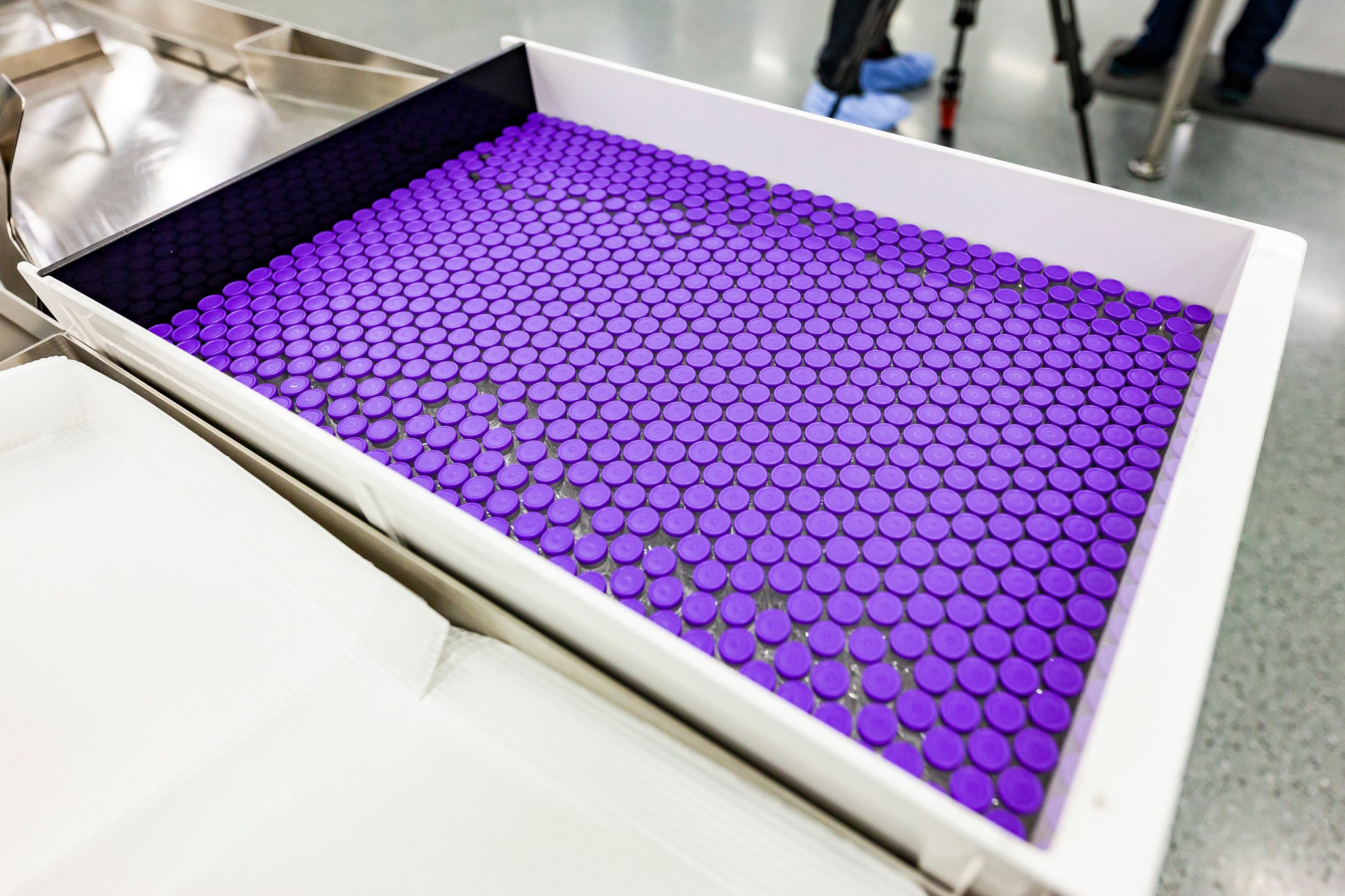

Step one: Manufacturers produce the vaccine

HHS receives regular production updates from Pfizer and Moderna. The manufacturers communicate estimated volumes in advance to help HHS plan before confirming real production numbers, which are piped into Tiberius.

Both vaccines are made using messenger RNA, a biotechnology that’s never been produced at scale before, and they need to be kept extremely cold until just before they go into a needle: Moderna’s must be kept at -25 to -15 °C, while Pfizer’s requires even lower temperatures of -80 to -60 °C. In the fall, it became clear that manufacturers had overestimated how quickly they could distribute doses, according to Deacon Maddox, Operation Warp Speed’s chief of plans, operations, and analytics and a former MIT fellow.

“Manufacturing, especially of a nascent biological product, is very difficult to predict,” he says. “You can try, and of course everybody wants to you try, because everybody wants to know exactly how much they’re going to get. But it’s impossible.”

PFIZER

This led to some of the first stumbles in the rollout. While training the states on how to use Tiberius, Operation Warp Speed entered those inflated estimates into a “sandbox” version of the software so states could model different distribution strategies for planning purposes. When those numbers didn’t pan out in reality, there was confusion and anger.

“At the end of December, people were saying, ‘We were told we were going to get this and they cut it back.’ That was all because we put notional numbers into the exercise side, and folks assumed that was what they were going to get,” says Maddox. “Allocation numbers are highly charged. People get very emotional.”

Step two: The federal government sets vaccine allocations

Every week, HHS officials look at production estimates and inventory numbers and decide on the “big number”—how many doses of each vaccine will go out to states and territories in total. Lately, they’ve been sticking to roughly 4.3 million per week, which they’ve found “allows us to get through lows in manufacturing, and save through highs,” Maddox says.

That number goes into Tiberius, which divvies up vaccines on the basis of Census data. Both HHS and media reports have sometimes described this step as using an algorithm in Tiberius. This should not be confused with any kind of machine learning. It’s just simple math based on the allocation policy, Maddox says.

Thus far, the policy has been to distribute vaccines according to each jurisdiction’s adult (18+) population. Maddox says the logic in Tiberius could easily be updated should Biden decide to do it on another basis, such as elderly (65+) population.

Once Operation Warp Speed analysts confirm the official allocation numbers, Tiberius pushes the figures to jurisdictions within their version of the software. An HHS employee then downloads the same numbers in a file and sends them to the CDC, where a technician manually uploads it to set order limits in VTrckS. (You can think of VTrckS as something like an online store: when health departments go to order vaccines, they can only add so many to their cart.)

Even that hasn’t been an exact science. Shortly before the inauguration, in a phone call with Connecticut governor Ned Lamont, outgoing HHS secretary Alex Azar promised to send the state 50,000 extra doses as a reward for administering vaccines efficiently. The doses arrived the next week.

The deal was representative of “the rather loose nature of the vaccine distribution process from the federal level,” Lamont’s press secretary, Max Reiss, told us in an email.

Step three: States and territories distribute the vaccine locally

State and territory officials learn how many vaccines they’ve been allotted through their own version of Tiberius, where they can model different distribution strategies.

Tiberius lets officials put data overlays on a map of their jurisdiction to help them plan, including Census data on where elderly people and health-care workers are clustered; the CDC’s so-called social vulnerability index of different zip codes, which estimates disaster preparedness on the basis of factors like poverty and transportation access; and data on hospitalizations and other case metrics from Palantir’s covid surveillance system, HHS Protect. They can also enter and view their own data to see where vaccination clinics and ultra-cold freezers are located, how many doses different sites have requested, and where vaccines have already gone.

Once states decide how many doses of each vaccine they want to send to each site, they download a file with addresses and dose numbers. They upload it into VTrckS, which transmits it to the CDC, which sends it to manufacturers.

PFIZER

Last week, Palantir rolled out a new “marketplace exchange” feature, effectively giving states the option to barter vaccines. Since the feds divvy up both Moderna and Pfizer vaccines without regard to how many ultra-cold freezers states have, rural states may need to trade their Pfizer allotment for another state’s Moderna shots, Maddox says.

When thinking about the utility of the system, it’s worth noting that many health departments have a shallow bench of tech-savvy employees who can easily navigate data-heavy systems.

“It’s a rare person who knows technology and the health side,” says Craig Newman, who researches health system interoperability at the Altarum Institute. “Now you throw in large-scale epidemiology…it’s really hard to see the entire thing from A to Z.”

Step four: Manufacturers ship the vaccines

Somehow, shipping millions of vaccines to 64 different jurisdictions at -70 °C is the easy part.

The CDC sends states’ orders to Pfizer and to Moderna’s distribution partner McKesson. Pfizer ships orders directly to sites by FedEx and UPS; Moderna’s vaccines go first to McKesson hubs, which then hand them off to FedEx and UPS for shipping.

Tracking information is sent to Tiberius for every shipment so HHS can keep tabs on how deliveries are going.

Step five: Local pharmacies and clinics administer the vaccine

At this point, things really start to break down.

With little federal guidance or money, jurisdictions are struggling with even the most basic requirements of mass immunization, including scheduling and keeping track of who’s been vaccinated.

Getting people into the clinic may intuitively seem easy, but it’s been a nightmare almost everywhere. Many hospital-based clinics are using their own systems; county and state clinics are using any number of public and private options, including Salesforce and Eventbrite. Online systems have become a huge stumbling block, especially for elderly people. Whenever jurisdictions set up hot lines for the technologically unsavvy, their call centers are immediately overwhelmed.

Even within states, different vaccination sites are all piecing together their own hodgepodge solutions. To record who’s getting vaccines, many states have retrofitted existing systems for tracking children’s immunizations. Agencies managing those systems were already stretched thin trying to piece together messy data sources.

PFIZER

It may not even be clear who’s in charge of allocating doses. Maddox described incidents when state officials contacted HHS to say their caps were too low in VTrckS, only to realize that someone else within their office had transferred doses to a federal program that distributes vaccines to long-term care homes, without telling other decision makers.

“Operation Warp Speed was an incredible effort to bring the vaccine to market quickly,” and get it to all 50 states, says Hana Schank, the director of strategy for public interest technology at the think tank New America. “All of that was done beautifully.” But, she says, the program paid little attention to how the vaccines would actually get to people.

Many doctors, frustrated by the rollout, agree with that sentiment.