The Making of Billy Wilder

Long before the award-winning Hollywood screenwriter and director Billy Wilder spelled his first name with a y, in faithful adherence to the ways of his adopted homeland, he was known—and widely published, in Berlin and Vienna—as Billie Wilder. At birth, on June 22, 1906, in a small Galician town called Sucha, less than twenty miles northwest of Kraków, he was given the name Samuel in memory of his maternal grandfather. His mother, Eugenia, however, preferred the name Billie. She had already taken to calling her first son, Wilhelm, two years Billie’s senior, Willie. As a young girl, Eugenia had crossed the Atlantic and lived in New York City for several years with a jeweler uncle in his Madison Avenue apartment. At some point during that formative stay, she caught a performance of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West touring show, and her affection for the exotic name stuck, even without the y, as did her intense, infectious love for all things American. “Billie was her American boy,” insists Ed Sikov in On Sunset Boulevard, his definitive biography of the internationally acclaimed writer and director.

Wilder spent the first years of his life in Kraków, where his father, the Galician-born Max (né Hersch Mendel), had started his career in the restaurant world as a waiter and then, after Billie’s birth, as the manager of a small chain of railway cafés along the Vienna-to-Lemberg line. When this gambit lost steam, Max opened a hotel and restaurant known as Hotel City in the heart of Kraków, not far from the Wawel Castle. A hyperactive child, known for flitting about with bursts of speed and energy, Billie was prone to troublemaking: he developed an early habit of swiping tips left on the tables at his father’s hotel restaurant and for snookering unsuspecting guests at the pool table. After all, he was the rightful bearer of a last name that conjures up, in both German and English, a devilish assortment of idiomatic expressions suggestive of a feral beast, a wild man, even a lunatic. “Long before Billy Wilder was Billy Wilder,” his second wife, Audrey, once remarked, “he behaved like Billy Wilder.”

The Wilder family soon moved to Vienna, where assimilated Jews of their ilk could better pursue their dreams of upward mobility. They lived in an apartment in the city’s First District, the hub of culture and commerce, just across the Danube from the Leopoldstadt, the neighborhood known for its unusually high concentration of recently arrived Jews from Galicia and other regions of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. When the monarchy collapsed, after World War I, the Wilders were considered to be subjects of Poland and, despite repeated efforts, were unable to attain Austrian citizenship. Billie attended secondary school in the city’s Eighth District, in the so-called Josefstadt, but his focus was often elsewhere. Across the street from his school was a tawdry “hotel by the hour” called the Stadion; he liked to watch for hours on end as patrons went in and out, trying to imagine the kinds of human transactions taking place inside. He also spent long hours in the dark catching matinees at the Urania, the Rotenturm Kino, and other cherished Viennese movie houses. Any chance to take in a picture show, to watch a boxing match, or to land a seat in a card game was a welcome chance for young Billie.

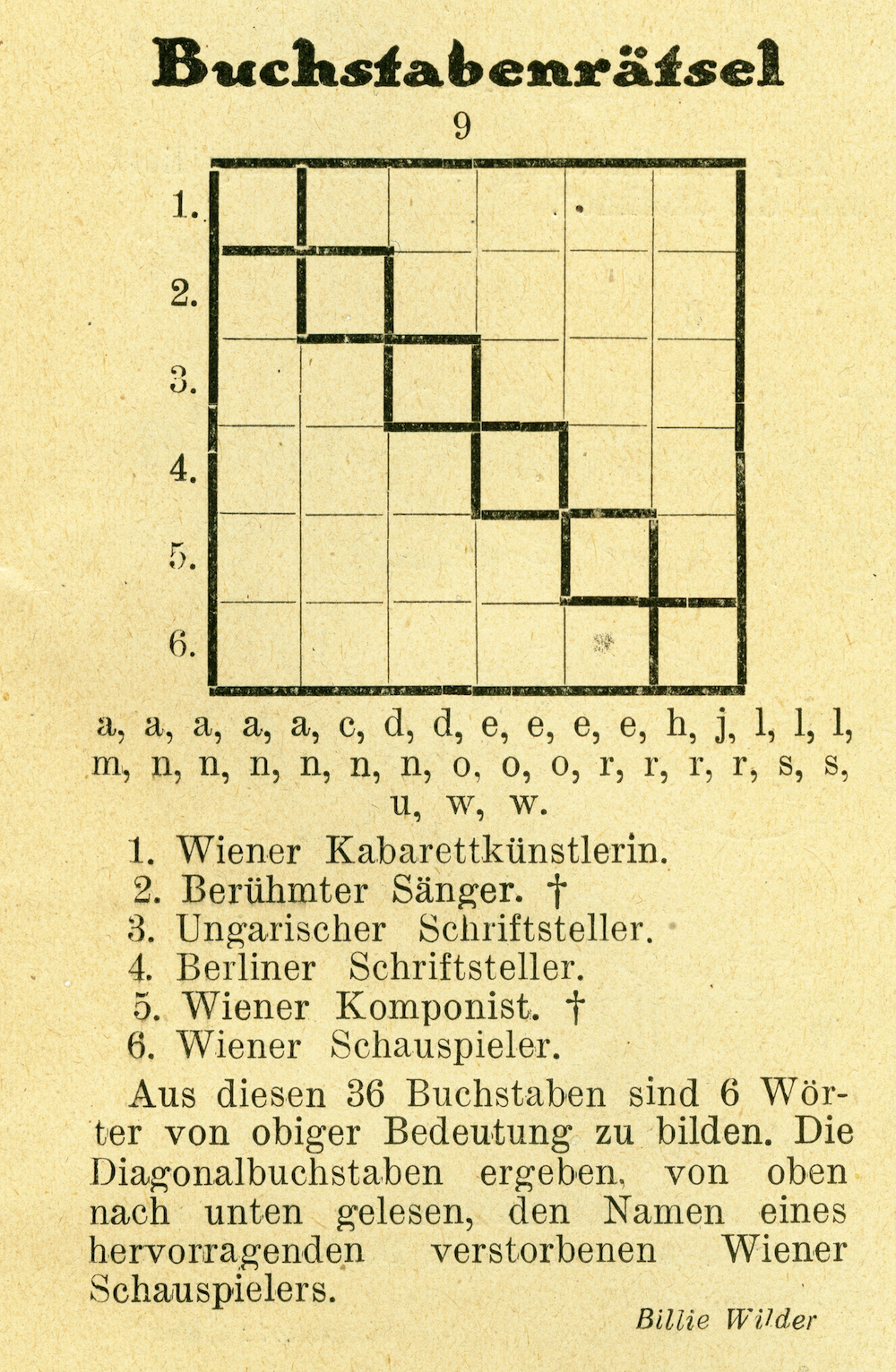

Although Wilder père had other plans for his son—a respectable, stable career in the law, an exalted path for good Jewish boys of interwar Vienna—Billie was drawn, almost habitually, to the seductive world of urban and popular culture and to the stories generated and told from within it. “I just fought with my father to become a lawyer,” he recounted for the filmmaker Cameron Crowe in Conversations with Wilder: “That I didn’t want to do, and I saved myself, by having become a newspaperman, a reporter, very badly paid.” As he explains a bit further in the same interview, “I started out with crossword puzzles, and I signed them.” (Toward the end of his life, after having racked up six Academy Awards, Wilder told his German biographer that it wasn’t so much the awards he was most proud of, but rather that his name had appeared twice in the New York Times crossword puzzle: “once 17 across and once 21 down.”)

In the weeks leading up to Christmas 1924, at a mere eighteen years of age and fresh out of gymnasium (high school), with diploma in hand, Billie wrote to the editorial staff at Die Bühne, one of the two local tabloids that were part of the media empire belonging to a shifty Hungarian émigré named Imre Békessy, to ask how he might go about becoming a journalist, maybe even a foreign correspondent. Somewhat naively, he thought this could be his ticket to America. He received an answer, not the one he was hoping for, explaining that without complete command of English he wouldn’t stand a chance.

Never one to give up, Billie paid a visit to the office one day early in the new year and, exploiting his outsize gift of gab, managed to talk his way in. In subsequent interviews, he liked to tell of how he landed his first job at Die Bühne by walking in on the paper’s chief theater critic, a certain Herr Doktor Liebstöckl, having sex with his secretary one Saturday afternoon. “You’re lucky I was working overtime today,” he purportedly told Billie. (It’s hard not to think of the cast of characters that emerge from the pages of his later screenplays—the sex-starved men in his American directorial debut, The Major and the Minor [1942], or in Love in the Afternoon [1957] or The Apartment [1960]—who bear a strong family resemblance to Herr Liebstöckl.) Soon he was schmoozing with journalists, poets, actors, the theater people who trained with Max Reinhardt, and the coffeehouse wits who gathered at Vienna’s Café Herrenhof. There he met the writers Alfred Polgar and Joseph Roth, a young Hungarian stage actor named László Löwenstein (later known to the world as Peter Lorre), and the critic and aphorist Anton Kuh. “Billie is by profession a keeper of alibis,” observed Kuh with a good bit of sarcasm. “Wherever something is going on, he has an alibi. He was born into the world with an alibi, according to which Billie wasn’t even present when it occurred.”

The Viennese journalistic scene at the time was anything but dull, and Billie bore witness, alibi or no alibi, to the contemporary debates, sex, and violence that occurred in his midst. He carried with him a visiting card with his name (“Billie S. Wilder”) emblazoned upon it, and underneath it the name of the other Békessy tabloid, Die Stunde, to which he contributed crossword puzzles, short features, movie reviews, and profiles. Around the time he was filing his freelance pieces at a rapid clip, a fiery feud was taking place between Békessy and Karl Kraus, the acid-tongued don of Viennese letters, editor and founder of Die Fackel (The Torch), who was determined to drive the Hungarian “scoundrel” out of the city and banish him once and for all from the world of journalism. To add to this volatile climate, just months after Billie began working for the tabloid, one of Die Stunde’s most famous writers, the Viennese novelist Hugo Bettauer, author of the best-selling novel Die Stadt ohne Juden (The City without Jews, 1922), was gunned down by a proto-Nazi thug.

“I was brash, bursting with assertiveness, had a talent for exaggeration,” Wilder told his German biographer Hellmuth Karasek, “and was convinced that in the shortest span of time I’d learn to ask shameless questions without restraint.” He was right, and soon gained precious access to everyone from international movie stars like Asta Nielsen and Adolphe Menjou to the royal celebrity Prince of Wales (Edward VIII)—to whom he devoted two separate pieces—and the American heir and newspaper magnate Cornelius Vanderbilt IV. “In a single morning,” he boasted in a 1963 interview with Playboy’s Richard Gehman, speaking of his earliest days as a journalist in Vienna, “I interviewed Sigmund Freud, his colleague Alfred Adler, the playwright and novelist Arthur Schnitzler, and the composer Richard Strauss. In one morning.” And while there may not be any extant articles to corroborate such audacious claims, he did manage to interview the world-famous British female dance troupe the Tiller Girls, whose arrival at Vienna’s Westbahnhof station in April 1926 the nineteen-year-old Billie happily chronicled for Die Bühne. A mere two months later he got his big break, when the American jazz orchestra leader Paul Whiteman paid a visit to Vienna. There’s a wonderful photograph of Billie in a snap-brim hat, hands resting casually in his suit-jacket pockets, a cocksure grin on his face, standing just behind Whiteman, as if to ingratiate himself as deeply as possible; after publishing a successful interview and profile in Die Stunde, he was invited to tag along for the Berlin leg of the tour.

In his conversations with Cameron Crowe, Wilder describes visiting Whiteman at his hotel in Vienna after the interview he conducted with him. “In my broken English, I told him that I was anxious to see him perform. And Whiteman told me, ‘If you’re eager to hear me, to hear the big band, you can come with me to Berlin.’ He paid for my trip, for a week there or something. And I accepted it. And I packed up my things, and I never went back to Vienna. I wrote the piece about Whiteman for the paper in Vienna. And then I was a newspaperman for a paper in Berlin.” Serving as something of a press agent and tour guide—a role he’d play once more when the American filmmaker Allan Dwan would spend his honeymoon in Berlin and, among other things, would introduce Billie to the joys of the dry martini—Wilder reviewed Whiteman’s German premiere at the Grosses Schauspielhaus, which took place before an audience of thousands. “The ‘Rhapsody in Blue,’ a composition that created quite a stir over in the States,” he writes, “is an experiment in exploiting the rhythms of American folk music. When Whiteman plays it, it is a great piece of artistry. He has to do encores again and again. The normally standoffish people of Berlin are singing his praises. People stay on in the theater half an hour after the concert.”

Often referred to as Chicago on the Spree, as Mark Twain once dubbed it, Berlin in the mid-1920s had a certain New World waft to it. A cresting wave of Amerikanismus—a seemingly bottomless love of dancing the Charleston, of cocktail bars and race cars, and a world-renowned nightlife that glimmered amid a sea of neon advertisements—had swept across the city and pervaded its urban air. It proved to be a perfect training ground for Billie’s ultimate migration to America, and a place that afforded him a freedom that he hadn’t felt in Vienna. As the film scholar Gerd Gemünden has remarked in his illuminating study of Wilder’s American career, “the American-influenced metropolis of Berlin gave Wilder the chance to reinvent himself.”

During his time in Berlin, Wilder had a number of mentors who helped guide his career. First among them was the Prague-born writer and critic Egon Erwin Kisch, one of the leading newspapermen of continental Europe, who was known to hold court at his table—the “Tisch von Kisch,” as it was called—at the Romanisches Café on Kurfürstendamm, a favorite haunt among Weimar-era writers, artists, and entertainers. (Wilder would hatch the idea for the film Menschen am Sonntag [People on Sunday, 1930]—on café napkins, the story goes—at the Romanisches a handful of years later.) Kisch not only read drafts of Wilder’s early freelance assignments in Berlin, offering line edits and friendly encouragement, but helped him procure a furnished apartment just underneath him in the Wilmersdorf section of the city. A well-traveled veteran journalist, Kisch had long fashioned himself as Der rasende Reporter (The Racing Reporter), the title he gave to the collection of journalistic writings he published in Berlin in 1925, serving as an inspiration and role model for Billie (a caricature of Wilder from the period encapsulates that very spirit).

“His reporting was built like a good movie script,” Wilder later remarked of Kisch. “It was classically organized in three acts and was never boring for the reader.” In an article on the German book market, published in 1930 in the literary magazine Der Querschnitt, he makes special reference to Kisch’s Paradies Amerika (Paradise America, 1929), perhaps a conscious nod to the nascent Americanophilia that was already blossoming inside him.

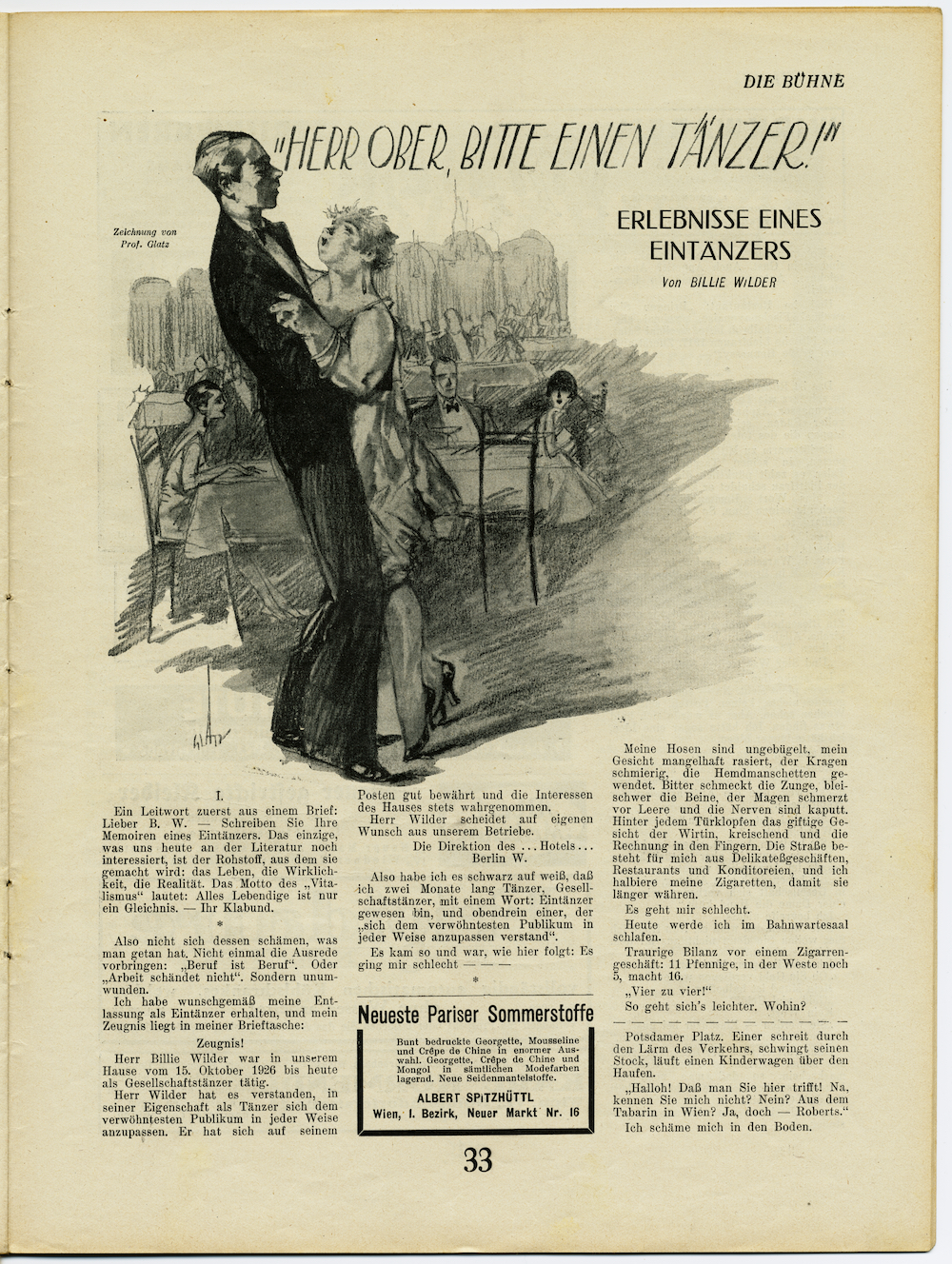

Among the best-known dispatches of the dozens that Billie published during his extended stint as a freelance reporter was his four-part series for the Berliner Zeitung am Mittag (B. Z.), later reprinted in Die Bühne, on his experiences working as a dancer for hire at the posh Eden Hotel. The piece bore an epigraph from yet another of his Berlin mentors, the writer Alfred Henschke, who published under the nom de plume Klabund and was married to the prominent cabaret and theater actress Carola Neher. In it, Klabund advises young writers, gesturing toward the contemporary aesthetic trend of Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity), to write about events as they really occurred: “The only thing that still interests us today about literature is the raw materials it’s made of: life, actuality, reality.” Since it’s Wilder, of course, the truth is mixed with a healthy dose of droll, martini-dry humor and a touch of unavoidable poetic license as he recounts the gritty details of his trade: the wealthy ladies of leisure who seek his services, the jealous husbands who glare at him, and the grueling hours of labor on the dance floor. “I wasn’t the best dancer,” he later said of this period, “but I had the best dialogue.”

Early on in the same piece, he includes a review of his performance attributed to the hotel management that in many way serves as an apt summation of his whole career: “Herr Wilder knew how to adapt to the fussiest audiences in every way in his capacity as a dancer. He achieved success in his position and always adhered to the interests of the establishment.” He put the skills he acquired on the dance floor to continued use on the page and on the screen, always pleasing his audience and ensuring his path to success. “I say to myself: I’m a fool,” he writes in a moment of intense self-awareness. “Sleepless nights, misgivings, doubts? The revolving door has thrust me into despair, that’s for sure. Outside it is winter, friends from the Romanisches Café, all with colds, are debating sympathy and poverty, and, just like me, yesterday, have no idea where to spend the night. I, however, am a dancer. The big wide world will wrap its arms around me.”

Title page of the four-part article “Herr Ober, bitte einen Tänzer!”—in which Wilder describes his days as a hotel dancer for hire—from its reprint in Die Bühne (June 2, 1927).

An ideal match for Billie arrived when, in 1928, the Ullstein publishing house, publisher of the Berliner Zeitung am Mittag, introduced a new afternoon Boulevard-Zeitung, an illustrated paper aimed at a young readership and bearing a title that would speak directly to them and to Wilder: Tempo. “It was a tabloid,” remarked the historian Peter Gay in his early study of the “German-Jewish Spirit” of the city, “racy in tone, visual in appeal, designed to please the Berliner who ran as he read.” The Berliners, however, quickly adopted another name for it: they called it Die jüdische Hast, or “Jewish Haste.” Billie, an inveterate pacer and man on the move, was a good fit for Tempo and vice versa (it was in its pages that he introduced Berliners to the short-lived independent production company Filmstudio 1929 and the young cineastes, including Wilder himself, behind its creation).

In 1928, after serving as an uncredited ghostwriter on a number of screenplays, Billie earned a solo writing credit for a picture that had more than a slight autobiographical bearing on its author. It was called Der Teufelsreporter (Hell of a Reporter), though it also bore the subtitle Im Nebel der Großstadt (In the Fog of the Metropolis), and was directed by Ernst Laemmle, nephew of Universal boss Carl Laemmle. Set in contemporary Berlin, it tells the story of the titular character, a frenetic newspaperman played by the American actor Eddie Polo, a former circus star, who works at a city tabloid—called Rapid, in explicit homage—and whose chief attributes are immediately traceable to Wilder himself. Unsurprisingly, perhaps, young Billie even has a brief appearance in the film, dressed just like the other reporters in his midst. “He performs this cameo,” write the German film scholars Rolf Aurich and Wolfgang Jacobsen, “as if to prove who the true Teufelsreporter is.” In addition to asserting a deeper connection to the city and to American-style tabloid journalism, Der Teufelsreporter lays a foundation for other hard-boiled newspapermen in Wilder’s Hollywood repertoire, from Chuck Tatum (Kirk Douglas) in Ace in the Hole (1951) to Walter Burns (Walter Matthau) in The Front Page (1974).

Further affinities between Wilder’s Weimar-era writings and his later film work abound. For example, in “Berlin Rendezvous,” an article he published in the Berliner Börsen Courier in early 1927, he writes about the favored meeting spots within the city, including the oversize clock, called the Normaluhr, at the Berlin Zoo railway station. Two years later, when writing his script for Menschen am Sonntag, he located the pivotal rendezvous between two of his amateur protagonists, Wolfgang von Waltershausen and Christl Ehlers, at precisely the same spot. For the same script, he crafted the character of Wolfgang, a traveling wine salesman and playboy, as a seeming wish-fulfillment fantasy of his own exploits as a dancer for hire. Likewise, in his early account of the Tiller Girls arriving by train in Vienna, there’s more than a mere germ of Sweet Sue and Her Society Syncopators, the all-girl band in Some Like It Hot (1959); there’s even a Miss Harvey (“the shepherdess of these little sheep”), anticipating the character of Sweet Sue herself. In a short comic piece on casting, Billie pays tribute to the director Ernst Lubitsch, a future mentor in Hollywood (many years later, Wilder’s office in Beverly Hills featured a mounted plaque designed by Saul Bass with the words HOW WOULD LUBITSCH DO IT? emblazoned on it). Finally, in his 1929 profile of Erich von Stroheim, in Der Querschnitt, among the many things young Billie highlights is Gloria Swanson’s performance in Stroheim’s late silent, Queen Kelly (1929). It was the first flicker of the inspired idea to cast Swanson and Stroheim as a pair of crusty, vaguely twisted emissaries from the lost world of silent cinema in Sunset Boulevard (1950).

*

By the time Wilder boarded a British ocean liner, the SS Aquitania, bound for America in January 1934, he’d managed to acquire a few more screen credits and a little more experience in show business, but very little of the English language (he purportedly packed secondhand copies of Ernest Hemingway’s A Farewell to Arms, Sinclair Lewis’s Babbit, and Thomas Wolfe’s Look Homeward, Angel in his suitcase). He had gone from a salaried screenwriter at UFA in Berlin to an unemployed refugee in Paris to an American transplant with twenty dollars and a hundred English words in his possession. “He paced his way across the Atlantic,” remarks Sikov. And soon he’d pace his way onto the lots of MGM, Paramount, and other major film studios, joining an illustrious group of Middle European refugees who would forever change the face of Hollywood.

Wilder’s acclaimed work in Hollywood, as a screenwriter and director, is in many ways an outgrowth of his stint as a reporter in interwar Vienna and Weimar Berlin. His was a raconteur’s cinema, long on smart, snappy dialogue, short on visual acrobatics. “For Wilder the former journalist, words have a special, almost material quality,” comments the German critic Claudius Seidl. “Words are what give his films their buoyancy, elegance, and their characteristic shape, since words can fly faster, glide more elegantly, can spin more than any camera.” Wilder’s deep-seated attachment to the principal tools of his trade as a writer is recognizable throughout his filmic career. He even provided an apt coda, uttered by none other than fading silent screen star Norma Desmond (Gloria Swanson) in Sunset Boulevard, when she learns that Joe Gillis (William Holden) is a writer: “words, words, more words!”

Noah Isenberg is the George Christian Centennial Professor and chair of the Department of Radio-Television-Film at the University of Texas at Austin. The author, most recently, of We’ll Always Have Casablanca: The Life, Legend, and Afterlife of Hollywood’s Most Beloved Movie (W. W. Norton, 2017), he is currently completing a book on Some Like It Hot. His writing has appeared in The Nation, The New Republic, Bookforum, The New York Review Daily, and The New York Times Book Review, among other outlets.

Excerpted from Billy Wilder on Assignment: Dispatches for Weimar Berlin and Interwar Vienna, edited by Noah Isenberg and translated by Shelley Frisch, published later this month by Princeton University Press. Copyright © 2021 by Noah Isenberg.