The Barn: Cathedrals to Nature

When renowned craftsman Robert Somerville moved to Hertfordshire, in southern England, he discovered an unexpected landscape rich with wildlife and elm trees. Nestled within London’s commuter belt, this wooded farmland inspired Somerville, a lifelong woodworker, to revive the ancient tradition of hand-raising barns.

This is a tale of forgotten trees, a local landscape, and an ancient craft.

The following is an excerpt from Barn Club by Robert Somerville and has been adapted for the web.

(All photography curtesy of Robert J. Somerville unless otherwise noted.)

There is an ancient elm barn in Wallington, Hertfordshire, not far from where I live. It is the barn at the heart of the story Animal Farm, written by George Orwell and published in 1945. I had come across the barn at the invitation of the owners, Nick and Diana Collingridge. They mentioned that George Orwell had lived in Wallington in the 1930s and that Manor Farm and its Great Barn were the setting for his book. As a child I had seen the Walt Disney animation of the story that depicts the farm and the barn, with the final, single rule painted in large white letters… ‘All animals are equal, but some animals are more equal than others.’ So one spring day I set out with Nick and Diana, who proudly showed me round the building that is now a place for the celebration of village events. The exterior is unremarkable, just black-painted horizontal boards and a dark slated roof. But the inside is another world. This is where the inspiration for Barn Club began.

The Great Barn, Wallington

To step inside this barn, into the darkness within its walls, is to take a step back in time. Not just to the 1930s, but far beyond, to an indeterminate, distant age. The barn is dark inside, almost black. Your eyes cannot make anything out. It is cool, still and silent, except for the slight rustle of the breeze over the slated roof high above. The smell is not of wood but of straw – old straw. This was once a threshing barn, but now has not an ear of wheat inside. The smell lingering in the air comes from countless harvests that crossed the threshold every autumn: the harvests of generations of farmers. Once inside it takes a while for your eyes to accustom to the gloom and the shape of the light switch next to you to reveal itself. Slowly, the old sodium lights warm up. But in those moments of semi-darkness you feel the atmosphere of the barn. Your eyes begin to distinguish the great supporting posts around you. You can almost imagine you are in a glade surrounded by tall trees during a twilight walk.

In these enormous barns you still feel the presence of trees.

All around is an array of timbers leading up and out from the posts, diminishing and arching as they go, like the branches and branchlets of a tree. High overhead, way up, are thin battens, the twigs, supporting the roof slates. The outer walls are completely wrapped with timber cladding to make an enormous wooden box that glows a subtle honey colour. When the lights have fully warmed you also see ahead a worn, gently undulating floor, crazed with cracks from wear over the decades. Entering the towering space feels both uplifting and humbling. Like many old barns there is a silence and peace within the encompassing structure. It has an undeniable beauty. People say that these barns are cathedral-like spaces. They are. They are like cathedrals to nature.

The Great Barn at Wallington was built over two hundred years ago, raised upright by human effort. The mortice and tenon joints were cut by hand, and the timber came from local woodland and hedgerows. No architects or engineers were involved in its design, it was made by common carpenters and farm labourers.

It has various Roman numerals, initials and dates scratched into the timbers inside, and, high up in the roof, one inscription reads, ‘Built E.F. Farmer 1786’. Another, on a post, reads, ‘G + C built 1786’. The lines of central posts are set out in a precise form in the pattern of the local carpentry tradition, well understood at the time and handed down from father to son. The barn is divided into four bays by the posts, with double cart doors in the front. There are two aisles either side of the long, central area. It is easily big enough to hold an entire harvest of wheat or, equally, a wedding feast.

It is still used by the village for local events and at just such a barn dance I met an elderly local who could remember a carpenters’ workshop in the nearby town of Royston. The company was called Farmer and Sons. The business is no longer there, but in 1976 the carpenters made half barrels as flower planters for the town to celebrate the jubilee of Queen Elizabeth II. It is tantalising to think that they were the same family of carpenters that had cut and raised the barn at Manor Farm. However, since the person who paid for the barn was a farmer named Edward Fossey, it is more likely that he is the ‘E.F. Farmer’ in the inscription, and that ‘G+C’ refers to the carpenters. I think that perhaps the latter is true. Most barns, being practical vernacular structures, carry no inscription at all. They were built by unknown craftsmen.

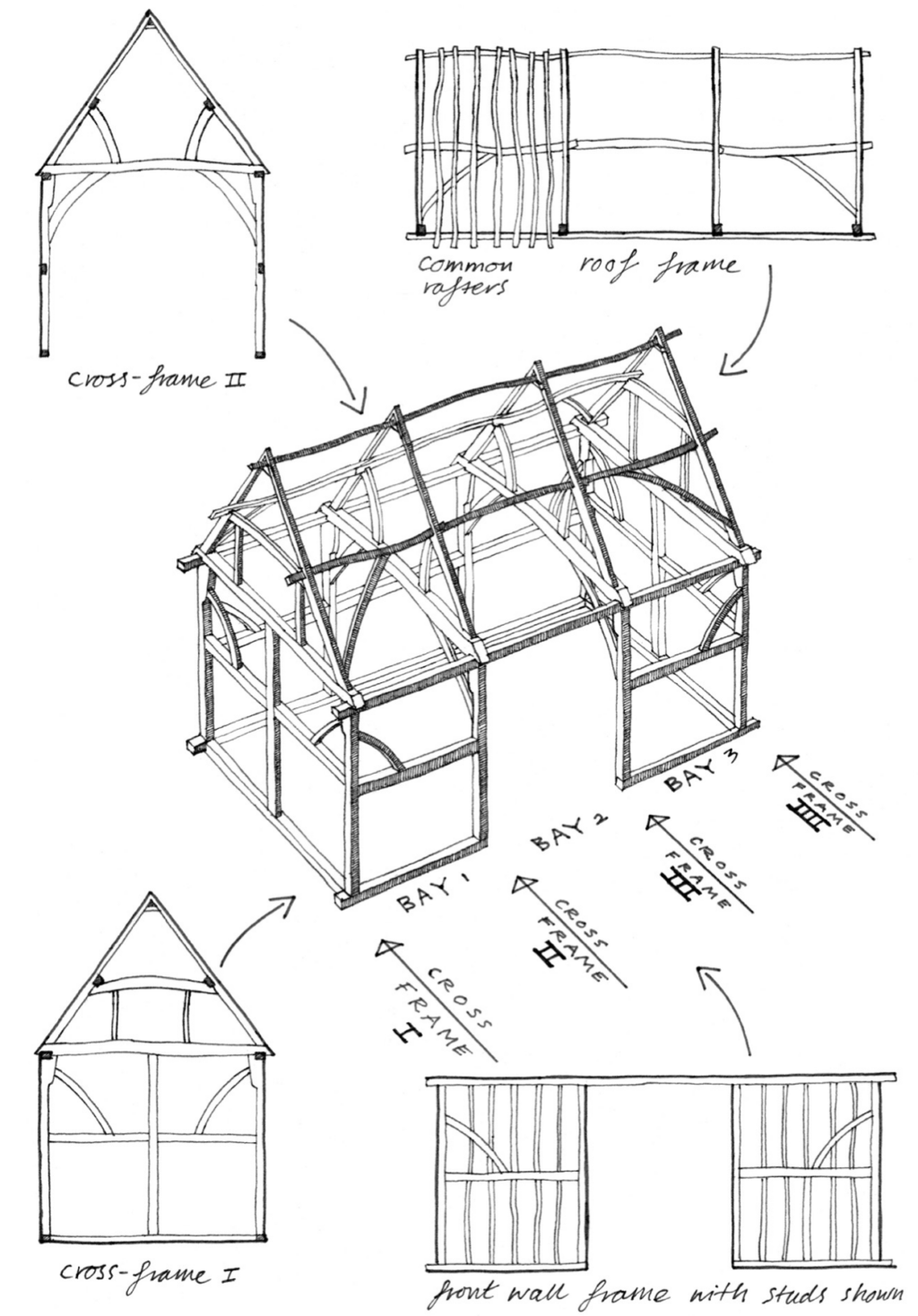

The bays, walls and roof of a typical Hertfordshire timber framed barn after Richard Harris.

Inscribing a timber with the date and their initials might occasionally be a final act of completion for the carpenter, but there are always other marks as well. Each piece of wood has a Roman numeral to locate it in the greater scheme of the construction, and there were indeed carpenter’s marks in this timber frame. Nick produced a torch so that we could shine a light up along the length of each piece of wood to highlight any more detail. There were the marks of pit saws and side axes as well as the just discernable thin lines of a carpenter’s scratch awl used to set out the timber joints. It feels very special to inspect these marks made over two hundred years beforehand. There is a kind of intimacy and linking of minds across the centuries as you closely observe these traces of the original carpenters’ work, perhaps the scratch of an awl made with the flick of the wrist in a fraction of a second all those years ago. Close examination of the heads of the main posts also revealed a curious feature. The posts widened at their heads to form projecting jowls and there were carved profiled shapes, about four inches long, at the chins of these jowls. (See top left image of diagram.) Within the whole of the structure, these jowl chins were rare places of deliberate, non-functional decoration.

A traditionally constructed aisled barn like this one, built at the end of the eighteenth century, is in itself unusual. It would have been made with materials and methods developed over millennia by local craftspeople in a time-honoured way, accepted and understood as the way things were done.

But it was also created just a few years before a wholesale transformation of the practice of village carpentry.

At about this date there was a shift to using imported conifers, machine-sawn timber, engineered truss design and metal fixing methods. Even the way of sawing wood was changing. The circular saw was ‘An entirely new machine for more expeditious sawing…’ patented in 1777 by Samuel Miller of Southampton. In 1799 Marc Isambard Brunel built the first steam sawmill at the Chatham Dockyard. Not long afterwards, in 1808, William Newberry of London invented the band saw.

The Wallington barn is one of the last of its kind in the region. I can imagine the head carpenter being a man who wanted to show the apprentices how things were done when he learnt his trade. Perhaps he wanted to show all the different styles of jowl chins to the young apprentices, knowing that they would soon be off to embrace the new styles, techniques and materials that were arriving in Royston. Certainly the great thatched barn at Wimpole Hall, just a few miles away in Cambridgeshire, and built a few decades later, would be built with an entirely new and modern approach. By then, the shift from village craft to industrial production was underway. In this sense the barn at Manor Farm was itself a final flourish of an age-old tradition. This tradition was destined to die out. By the end of the nineteenth century the carpenters who had made the Wallington barn would also have died. Fewer and fewer people were alive who could explain how these magnificent buildings were made, leaving only folklore and folk memory. Tools that were once in daily use can sometimes be seen today decorating the walls of country pubs; their true meaning lost on a modern clientele. For example, dividers, sometimes called compasses or ‘points’, were universally used to transfer measurements before tape measures. The two sharp points of a pair of dividers can be adjusted. They are set to record a particular dimension, to be reproduced with extreme accuracy somewhere else. They are an amazingly useful tool and one that all sorts of trades would once have used. Points were such a fundamental tool in the process of making that William Blake used them in his image of the godlike Urizen creating and ordering the universe. It is a very striking image, with the creator wielding a pair of dividers. The significance of the metaphor would have been instantly recognisable to Blake’s eighteenth-century audience.

You also might like…

“Barn Club” came into being in 2015 when a few local people became fascinated by Robert’s intention to build a new traditional elm barn on his family’s smallholding.

They wanted to get involved. Working outdoors in the fresh air, with age-old hand tools and techniques such as plumb-bob scribing, is a richly rewarding experience … all culminating in the day of the barn raising. More and more people became involved and several carpentry courses were incorporated into the program. Complete beginners, and people of all shapes and sizes, found their place in the team and often surprised themselves as they discovered how easy it is to pick up these “village carpentry” skills. The fact that people want to volunteer demonstrates how much the skilled use of hand tools is a boost to our physical and mental well-being.

[embedded content]