The Art of the Cover Letter

“If I write as though I were addressing readers, that is simply because it is easier for me to write in that form. It is a form, an empty form—I shall never have readers.” —Fyodor Dostoyevsky, Notes from Underground

The muses don’t sing to cover letter writers—they’re busy with the poets. But me? I transact exclusively in unloved prose. No one loves cover letters, but everyone needs a job. So my business, editing them, always booms.

My process may prove unorthodox, so let me offer a disclaimer before we begin. In the butchery of cover letter editing, one removes metaphors with chainsaws, cauterizes complexity with hot iron, and amputates anything more ambiguous than a grunt. I have no mercy for the saccharine cant of wild-eyed naïfs who write, “I would be thrilled to work as an entry-level associate.”

Because you wouldn’t.

A newborn’s barbaric yawp can thrill.

Doing what spring does with the cherry trees can thrill.

“Providing general administrative support in a fast-paced office” will never thrill you.

I’ll say this: what I have done to language in the service of cover letters haunts me. At worst, cover letters strain one’s faith that words convey meaning at all, let alone that sentences can shimmer, steal breath, or gird spines. I spend each day climbing mountains of junky paragraphs, scavenging for hunks of usable scrap—like so much copper wire—my senses deadened by the incessant clang of multipart adjectives.

“I am detail-oriented,” they write.

“My skills are well-suited,” they aver.

“I am a team player,” they fart onto the page.

As if these injuries to the expressive purpose have no consequence for reader and writer.

I describe cover letter composition in terms akin to the balancing acts of trick seals nosing beach balls aloft in exchange for applause and morsels of fish. In less than one page of text, a cover letter describes one’s qualifications by achieving three objectives: (a) expressing authentic-seeming interest in an organization’s mission and culture, (b) demonstrating adequate proof of having mobilized pertinent skills in previous contexts, and (c) communicating with sufficient obeisance to norms of professional décor.

If you want to be a seal, I’m the best trainer in the circus. We can be done in minutes.

But to understand cover letters will take longer.

*

As the worst of the Great Recession finally began to wane in 2013, The Atlantic published an article by Stephen Lurie on the history of cover letters. Then, as now, an interest in the cover letter ballooned as applicants flooded a desperate job market. Lurie argues, with a suspicious specificity, “The first use of ‘cover letter’ in the context of employment is on September 23, 1956.” In his telling, that day marked the moment that cover letters commenced their association with job applications because one was requested in the New York Times.

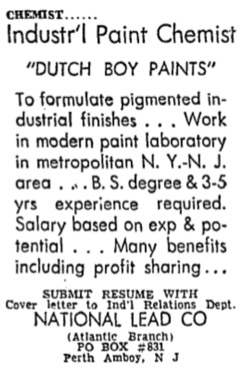

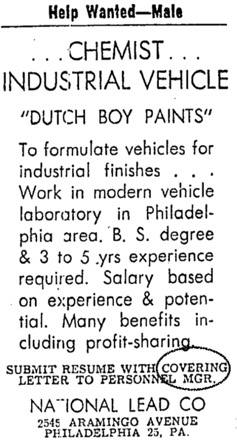

As evidence, he points to an ad in the classifieds section for a job at Dutch Boy Paints, which asks that candidates, “submit résumé with cover letter.” This presupposes that a history of the cover letter begins with something being named a cover letter, which does not seem convincing. Writers don’t name genres and then figure out what to write. The laws of genre do not mimic laws written by legislatures, in which case language dictates practice. Rather, conventions and rules begin to coalesce first. Practices evolve. Habits begin to form. And only then do names get attached to them.

I’m not merely guessing here. Just one week earlier (on September 16, 1956), Dutch Boy Paints solicited applications for the same position in the Times. In most general respects, it parrots the call from September 26 that Lurie cites. But it differs in an important respect, requesting not a cover letter, but a covering letter. It seems very improbable that a wholly new genre of professional communication evolved in seven days. To pinpoint the moment of a genre’s conception proves tricky, and it is difficult to know when exactly we began to (mis)communicate with one another in a brand-new way. Neither the novel nor the epic poem nor the cover letter had a clear and datable first.

*

At the age of nineteen in 1771, Benjamin Thompson married the widow Sarah Rolfe, and instantly became one of the wealthiest men in the colony of New Hampshire. A 1950 article written by Sanborn C. Brown and Elbridge W. Stein in the American Journal of Police Science reveals Thompson’s minor role in the history of the American Revolution and his curious contribution to the history of cover letters. The authors claim Thompson was responsible, in a three-page letter dated May 6, 1775, for “the first known example of the use of secret ink in the American Revolution.” The document in question actually represents two interwoven texts. A short and innocuous note—which would have been visible to the naked eye upon its original delivery—reads as follows:

Sir / If you will be so kind as to deliver to / Mr. [redacted] of Boston, the Papers which I / left in your care, and take his Receipt for the same, / You will much oblige / Your Humble Servant / [erased].

But interlaced between these lines snakes a much longer message that divulges the size of the gathering Continental Army. Amid details of men and munitions, Thompson laments, “Upon my refusing to bear Arms against the king I was more than ever suspected by the people in this part of the country.” These lines, composed in invisible ink, would have required the application of chemicals or heat to become legible.

This longer message comprises the true meaning of the correspondence. The thousand-word secret message surrounds and punctures the inane three-line message and would not have been legible to a recipient without the technological means to develop it.

Or in Brown and Stein’s words, “The letter was originally written in two parts, a short visible cover letter and a long invisible part which was left developed by the recipient.”

To read Brown and Stein literally suggests that the first cover letter in the New World had nothing to do with job applications at all. When Brown and Stein refer to Thompson’s espionage as an act of cover letter authorship, they potentially expand the universe of what it means to perform that act. Perhaps a cover letter always implies a cover-up, a cover story, an omission, a disguise, a lie.

Every cover letter dribbles onto the page a few syllables about self-worth in language that reduces human value to sets of marketable skills, attempting to fit a person to a particular labor slot. The best letters, given the rules of job applications, succeed in rendering entirely secret the full truth of the writer’s selfhood.

*

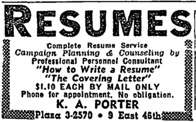

For as long as we have been writing cover letters, or covering letters, and whatever preceded covering letters, writers have sought the support of those who have mastered the craft. Lurie describes what he believes is the earliest example of an advertisement for how-to guides on writing cover letters. He says, “The first true sign that cover letters were mainstream enough to cause job applicants some anxiety was an advertisement in 1965, in the Boston Globe.” Again, it should come as no surprise, that one will find an advertisement for a how-to guide on “the covering letter” (again in the New York Times) in August 1955—more than a decade before the example that Mr. Lurie cites in the Boston Globe, and indeed much closer to the pair of Dutch Boy ads.

I press back on Lurie’s timeline, not to denigrate a fellow historian of cover letters—indeed, I laud anyone interested enough in cover letters to investigate them in the first place. Rather, it seems important to return to the refrain: what frustrates job applicants in their composition of cover letters proves not to have anything to do with what that genre is named, but on the arbitrary demand to account for one’s value in the form of a page of text. If we were to trace the earliest ever attempt at self-aggrandizing bluster by a job applicant, we would do best to start with the Ancient Greeks, not with mid-twentieth-century America.

*

“No one will read this,” my advisees lament, often as I am reading their cover letter right in front of them. I know they mean that no one important will read it.

I don’t count.

Regardless, I will read it closely, provide margin notes and extensive line edits, make recommendations related to font selection, and so on. In the end, I may prove the only person to read the letter. Certainly no one will read it more carefully.

Given this attention, I wonder: Who could the letter have been meant for, but for me?

I recently came across an article from The Saturday Evening Post, which in 1947 ran a story about three copies of a “covering letter” (there’s that tricky -ing suffix again) dropped from a B-29 bomber—taped to balloon-borne radio instruments—just before the world’s third atom bomb detonated over Nagasaki. Three Manhattan Project scientists had written the letter, addressing it to Japanese physicist Ryokichi Sagane of the Imperial University. Years earlier, Sagane had been their colleague. Now an adversary, they warned him desperately, “Unless Japan surrenders at once, this rain of atomic bombs will increase many times in fury.”

The letter did not reach Sagane until after the war, though copies that fell on Japan from those balloons were indeed retrieved by what I can only imagine were very confused civilians. One made its way, years later, to the archives of Washington State University, and one of the original authors added his signature to it.

When dropping a letter from a plane over enemy terrain, before unleashing the deadliest weapon ever used, I wonder who these scientists thought that they were actually addressing. They must have known that the odds of the letter reaching the eyes of their intended reader—particularly in time to make any kind of difference in the direction of world affairs—were slim.

The question, implied in a different context by Jacques Lacan in his reading of Edgar Allan Poe’s story “The Purloined Letter,” is whether the intention of the letter writer has any kind of significance. This may seem obvious, but whomever the letter ultimately reaches—regardless of the letter writer’s intentions—is the letter’s audience.

You may very well address your cover letter “To whom it may concern.” The specific “whom” does not matter. You write this letter, send it off with your hopes and ambitions, imagine yourself in the role of associate. Surely, this job will transform your life and your career trajectory! And this letter will get you there.

The cover letter is not written with any expectation of readership or audience. It is written with hope and desperation in equal measures. One writes under conditions of duress, anxiety, optimism, nausea, arrogance, and deep insecurity. And in these respects, the address to no one—writing for an imagined and idealized audience—might be the only redeeming quality of the whole endeavor. For in this, you are not unlike Dostoyevsky’s Underground Man, who also writes to no one. You are writing for the only audience you could hope to reach if you wrote honestly and with your whole heart: yourself.

*

My work helps others find work. If you know a way out of this labor camp, tell me.

But for now, there’s a recession, and a pandemic, and my inbox swells with cover letters. My mother—a pediatric nurse for more than forty-five years—raised me to be mindful of how I could use the tools I have to help others. The gods blessed and cursed me with the ability to turn the muck and dross of corporate-speak into something that can pass for English. And in that margin can lie the difference between garble and dignity.

Let the poets have the work of inspiring with song, I say. For now, I tie the strings of my bloodied smock behind my back and pick up my hacksaw.

There is work to be done.

A-J Aronstein is a dean at Barnard College, where he runs the career advising center. His work has appeared or is forthcoming in the New York Times, The Paris Review Daily, Electric Literature, Los Angeles Review of Books, Guernica, and The Millions.