Surprising Signs of Neanderthal Adaptability Discovered in Ancient Rock Shelter

On an ordinary morning long ago, at the foothills of what are now the Pyrenees of Spain’s Iberian Peninsula, a group of Neanderthals woke, greeted the day, and set about their tasks in the growing light.

They could not have known that, tens of thousands of years later, modern humans scurrying about in the dirt would find traces of their existence, and be able to reconstruct details about how they lived their lives. That, however, is exactly what archaeologists have now done – discovering that Neanderthals were far more resilient than we suspected.

The excavation of a recently discovered rock shelter site called Abric Pizarro has turned up thousands of artifacts dated to between 65,000 and 100,000 years ago, including stone tools and animal bones that can tell us a lot about the Neanderthal way of life during a period for which few remnants remain.

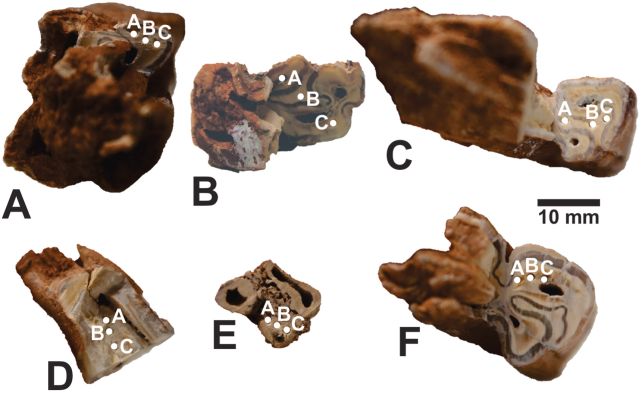

And, surprisingly, those bones include the remains of many small animals – revealing that Neanderthals were versatile hunters, able to adapt their lifestyle to food availability.

“Our surprising findings at Abric Pizarro show how adaptable Neanderthals were,” says zooarchaeologist Sofia Samper Carro of the Australian National University.

“The animal bones we have recovered indicate that they were successfully exploiting the surrounding fauna, hunting red deer, horses and bison, but also eating freshwater turtles and rabbits, which imply a degree of planning rarely considered for Neanderthals.”

Neanderthals (Homo neanderthalensis) constituted one of the closest hominid relatives to modern humans (Homo sapiens), to the point that the two species repeatedly mated, and may not even be a separate species at all. But for some reason, there has been a persistent notion that Neanderthals were primitive, uncultured, and cognitively less developed than today’s humans.

In recent years, more and more discoveries have been contradicting this notion. Neanderthals made sophisticated tools, and decorated their environment with different kinds of art.

The main problem with decoding the lives of the Neanderthals is the survivability of the artifacts they left behind. Neanderthals went extinct some 40,000 years ago, and most of the detritus of their lives has succumbed to the ravages of time, decay, and erosion. What we have been able to recover suggests that the Neanderthals were hunters only of large prey, such as horses and rhinoceroses.

Abric Pizarro was a Neanderthal rock shelter discovered in 2008, and archaeologists have been carefully working to dig up its secrets since 2009. Samper Carro and her colleagues have now conducted a thorough survey of some of the artifacts recovered.

The researchers conducted optically stimulated luminescence dating to determine the age of the sediment in which the objects were buried; that’s a technique that can determine when a mineral sample was last exposed to sunlight.

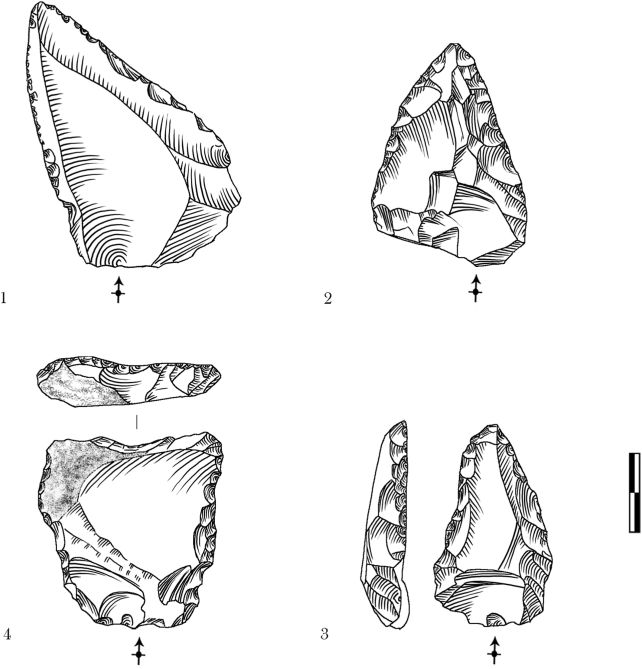

They also analyzed pollen grains and bones found at the site, looking at the latter for signs of cut marks and gnawing. And they studied the stone tools, to gauge the knapping techniques and technologies available to the people who once inhabited Abric Pizarro.

The dating confidently showed the site was inhabited by Neanderthals roughly 70,000 years ago, and the artifacts showed that these Neanderthals were skilled.

“The bones on this site are very well preserved, and we can see marks of how Neanderthals processed and butchered these animals. Our analysis of the stone artifacts also demonstrates variability in the type of tools produced, indicating Neanderthals’ capability to exploit the available resources in the area,” Samper Carro says.

“They clearly knew what they were doing. They knew the area and how to survive for a long time.”

This should not come as much of a surprise. Neanderthals had been living happily in Europe for around 300,000 years before their extinction.

But the reasons why Neanderthals went extinct are not entirely clear to us. If they had been inflexible in their approach to food availability, that would have been a clue. The fact that they were adaptable can also tell us something about why they died out.

The rapid decline of the Neanderthals after surviving for so long coincided with the arrival of modern humans, a juxtaposition that does not bode well for the role of our own species in their disappearance. It could very well be the work of Homo sapiens that all we have left of the Neanderthals is a scant artifact record, and traces of DNA in our genome.

Now, we also have Abric Pizarro, and researchers are keen to sift out its secrets, to learn more about the mysterious lives of these long-lost cousins.

“Future studies will characterize the Neanderthal occupations documented in Abric Pizarro in more detail,” the authors write.

The research has been published in the Journal of Archaeological Science.