Staff Picks: Marriage, Martinis, and Mortality

A candid attitude about death and sincere empathy for grief are wrongly put at odds: to speak with frankness is regarded as insensitive, and condolences are meant to come from the heart. But often it is the card-aisle euphemisms that ring false. Sigrid Nunez’s most recent novel, What Are You Going Through, is unflinching on the theme of mortality and thus presents an openhearted honesty so rare it feels thirst-quenching. The two major elements at play: dread about the end of the world, by way of the narrator’s ex, an academic who delivers lectures about what humanity has done to ensure the demise of everything; and the imminent death of the narrator’s friend, either by cancer or (the friend hopes) her own hand. I don’t want to call this a story without hope, because to face inevitability with the dichotomous perspective of hope versus no hope … you may as well be armed with Hallmark. Nunez renders the pain of aging, especially as a woman, with quiet humor and philosophy brought to life by sharp characters. Readers of Nunez’s previous novel, The Friend, will recognize these qualities, but here they feel honed, turned up in intensity. Afterward, I flipped open a book by a young person, about young people, and how silly it all seemed. —Lauren Kane

I recently picked up a short essay by Michel Foucault about René Magritte’s The Treachery of Images in an effort to sate my appetite for writing about visual art. This Is Not a Pipe—translated and edited by James Harkness—made for one of the most accessible experiences I’ve had with reading theory. A short, dense work of little more than sixty pages, Foucault’s essay is, first and foremost, fun. He displays a deft humor within his analysis without sacrificing any intentionality or depth. While many of Foucault’s most complicated puns had to be omitted due to the impossibility of accurately translating them, Harkness provides ample footnotes and endnotes to explain the voice of the philosopher as it pertains to the intersection of whimsy and scrutiny. As a result, the work of translation enters the conversation about words, signs, and how they imperfectly relate to each other. But in that gulf—whether large or small—lies room for investigation as to how we manage to communicate through words and images anyway. Ultimately, the answer rests in our willingness to stick with discourses until they break apart to reveal a truth that’s altogether too grand for a pipe. Or a painting of a pipe. Or a painting of a not-pipe. —Carlos Zayas-Pons

Barely a page went by in Meena Kandasamy’s When I Hit You: Or, A Portrait of the Writer as a Young Wife without my wanting to underline at least a sentence. Kandasamy’s novel, which was short-listed for the 2018 Women’s Prize for Fiction in the UK but only recently came out in the U.S., follows a young writer in Chennai who marries a leftist college lecturer and quickly finds herself trapped in an abusive marriage. Kandasamy’s prose is electric, at once brave and poetic and satirical as she pokes holes in the mythoi of marriage, gender, intellectualism, and art. “Quickly realizing that the more she changes, the more things remain the same,” she writes in a parody of a movie’s publicity material toward the book’s beginning, “the writer begins to essay the mock role of an intellectual in a bid to save her marriage. Faking orgasmic delight in discussing the orthodoxy of the Second International, or dismissing the postmodern idea of deconstruction, she coasts along with aplomb.” In chapters that begin with epigraphs from Kamala Das, Pilar Quintana, Elfriede Jelinek, Anne Sexton, and more, Kandasamy is unflinching in her portrayal of both domestic violence and how art can grapple with abuse. —Rhian Sasseen

To break up the time in that slow, strange week between Christmas and New Year’s, I wanted to read something that felt vibrant, vital, and alive. I picked up Sarah Crossan’s Here Is the Beehive, a novel written in free verse. I liked the look of all that space, the short sentences and line breaks letting me feel like I was accomplishing something with each quickly turned page, the sparsity of the prose giving way to gorgeous passages and subtle depth. Free from the excesses of typical fiction writing, the flashes of dialogue and half-formed thoughts come within a narrative consumed by grief and then, later, obsession. The titular line appears in a nursery rhyme, but the anxiety of the novel lends it an eerie cadence: “Here is the beehive. / Where are the bees? / Hidden away where nobody sees.” I’ve been thinking about this ever since, how so much happens below the surface, behind closed doors, and in unexpressed thoughts—the body a beehive with its barely concealed bees. —Langa Chinyoka

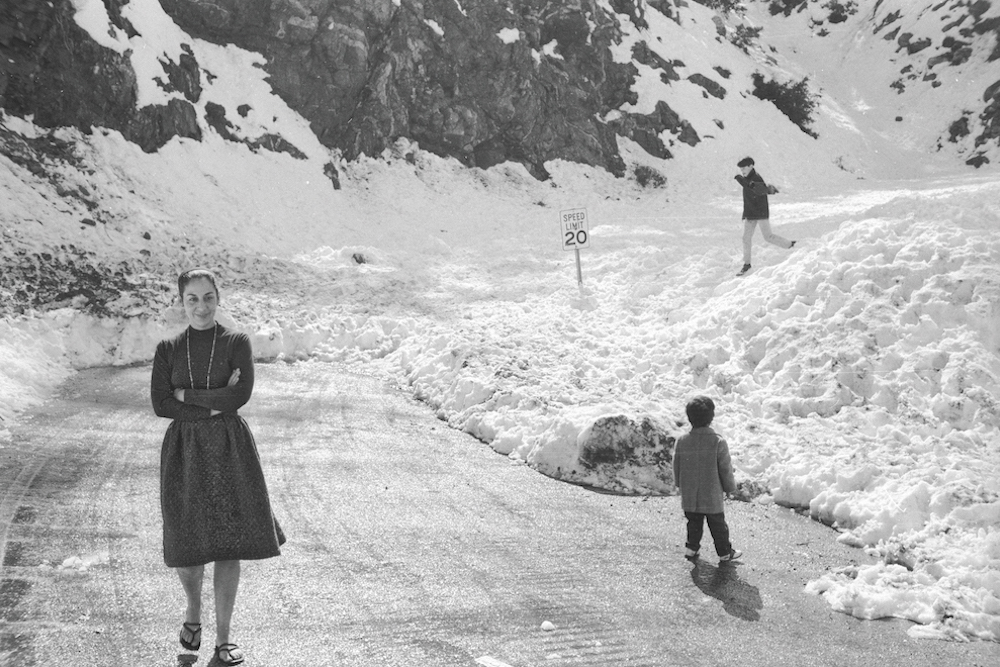

For me, the oral/visual history of the late Luchita Hurtado would have been worthwhile just for the anecdote about drinking martinis with Agnes Martin—though I recognize I’m a biased audience (toward Martin, toward the confluence of artists working in New Mexico in the seventies, and yes, toward martinis). Fortunately, the eponymous book, published in December by Hauser & Wirth, offers much more than that: it is a compelling portrait of an artist as she approaches her hundredth birthday (a milestone she missed by a few months—she died this past August, at ninety-nine), a concise summary of her peripatetic art practice (which included self-portraits, botanical drawings, and numinous paintings of the sky), and a beautifully designed object (the pressed flowers on transparent inserts feel, in particular, like a gift to the reader). The spine of the volume is a series of exchanges with the curator Hans Ulrich Obrist, with whom Hurtado developed a friendship near the end of her long life; their conversations about her biography and creative practice are interspersed with portfolios of her art and photos from her personal archive. In the last four years of her life, Hurtado was “lavished with attention, praise and exhibitions,” as Roberta Smith notes in a review of her latest exhibition, but what the book shows again and again—as illustrated by those martini lunches with Martin—is that the attention didn’t matter; the making a rich life did. —Emily Nemens