Scientists Discover Mosquitoes Are Using Infrared to Track Humans Down

There’s something about us that mosquitoes just love. In addition to our smell, and our breath, our exposed skin acts as a kind of neon sign advertising that this blood bar is open for business.

That’s because mosquitoes use infrared sensing in their antennae to track down their prey, a new study has found.

In many parts of the world, mosquito bites are more than an irritation, capable of spreading pathogens like dengue, yellow fever, and Zika virus. Malaria, spread by the Anopheles gambiae mosquito, caused more than 600,000 deaths in 2022, according to World Health Organization statistics.

To avoid serious disease, or even just a case of maddening itchiness, we humans are pretty keen to find ways to prevent mosquito bites.

Research led by scientists from the University of California Santa Barbara (UCSB) found that mosquitoes use infrared detection – along with other cues we already knew about, like a nose for the CO2 in our breath, and certain body odors, to seek out hosts.

“The mosquito we study, Aedes aegypti, is exceptionally skilled at finding human hosts,” says UCSB molecular biologist Nicholas Debeaubien.

But mosquitoes’ vision isn’t too good, and smells can be unreliable if it’s windy or the host is moving. So the team suspected infrared detection might offer the insects a reliable aid in finding food.

Only female mosquitoes drink blood, so the researchers presented cages each containing 80 female mosquitoes (around 1-3 weeks old) with a variety of dummy ‘hosts’ represented by combinations of thermoelectric plates, CO2 at the concentration of human breath, and human odors, and recorded five minute videos to observe their host-seeking behaviors.

They defined these as “a mosquito landing, walking and extending its proboscis through the mesh of the cage, which is reminiscent of a female landing on a human and then walking while sampling the skin surface with its labellum.”

Some of the mosquitoes were presented with a thermoelectric plate set to the average temperature of human skin of 34 degrees Celsius (93 °F), which also served as a source of infrared radiation. Others were set to an ambient temperature of 29.5 °C – a temperature mosquitoes are known to enjoy, but emits no infrared.

Each cue on its own – CO2 , odor, or infrared – failed to pique the mosquitoes’ interest. But the insect’s apparent thirst for blood increased twofold when a setup with just CO2 and odor had the infrared factor added.

“Any single cue alone doesn’t stimulate host-seeking activity. It’s only in the context of other cues, such as elevated CO2 and human odor that IR makes a difference,” says UCSB neurobiologist Craig Montell.

The team also confirmed the mosquitoes’ infrared sensors lie in their antennae, where they have a temperature-sensitive protein, TRPA1. When the team removed the gene for this protein, mosquitos were unable to detect infrared.

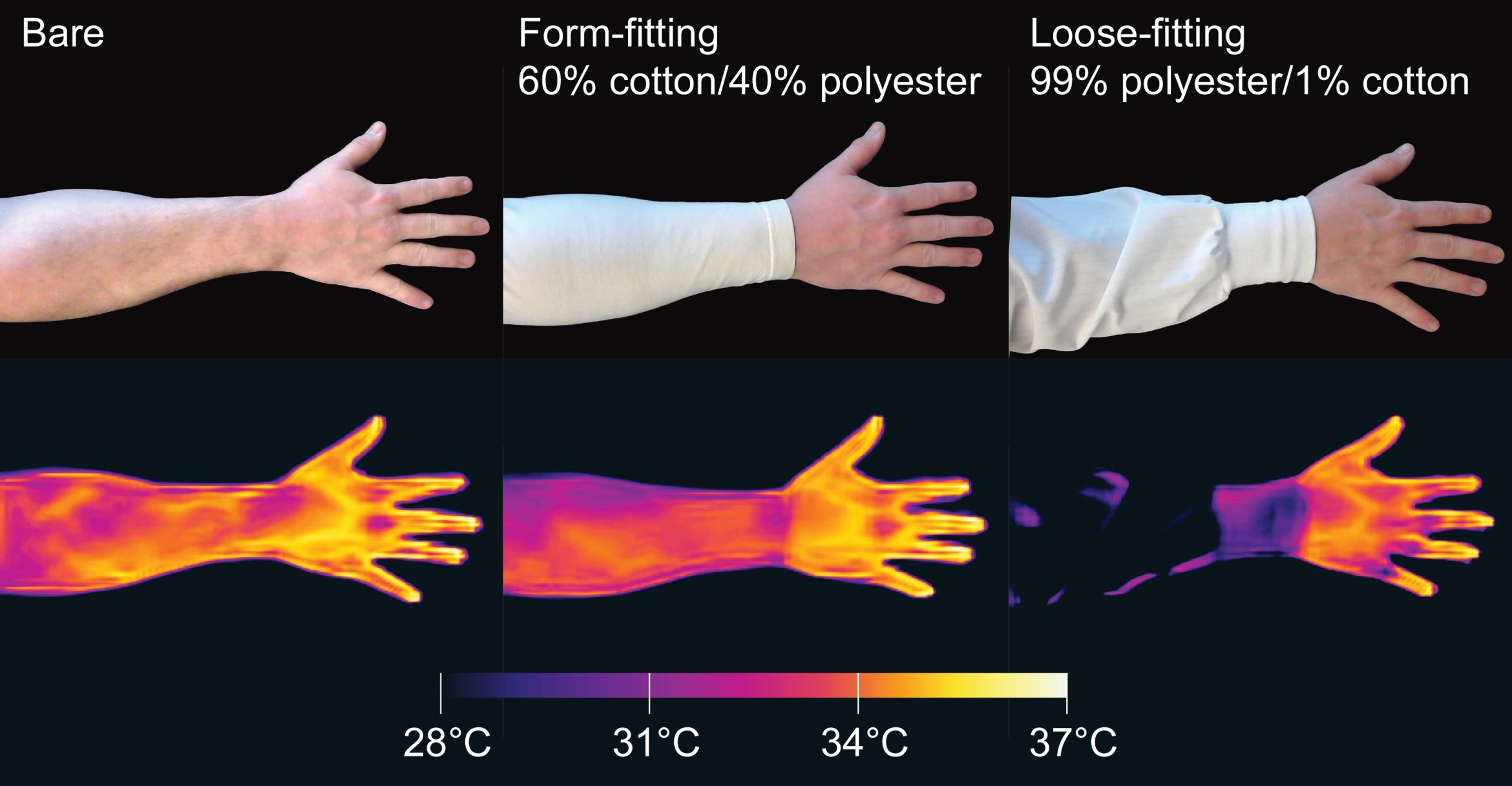

The findings help explain why mosquitoes seem particularly drawn to exposed skin, and why loose-fitting clothing – through which infrared is dissipated – is such an effective invisibility cloak against them.

It might also lead to some slightly more high-tech defenses against mosquitoes, like the potential to create traps that employ skin-temperature thermal radiation as a lure.

“Despite their diminutive size, mosquitoes are responsible for more human deaths than any other animal,” DeBeaubien says.

“Our research enhances the understanding of how mosquitoes target humans and offers new possibilities for controlling the transmission of mosquito-borne diseases.”

This research is published in Nature.