Reading the Room: An Interview with Paul Yamazaki

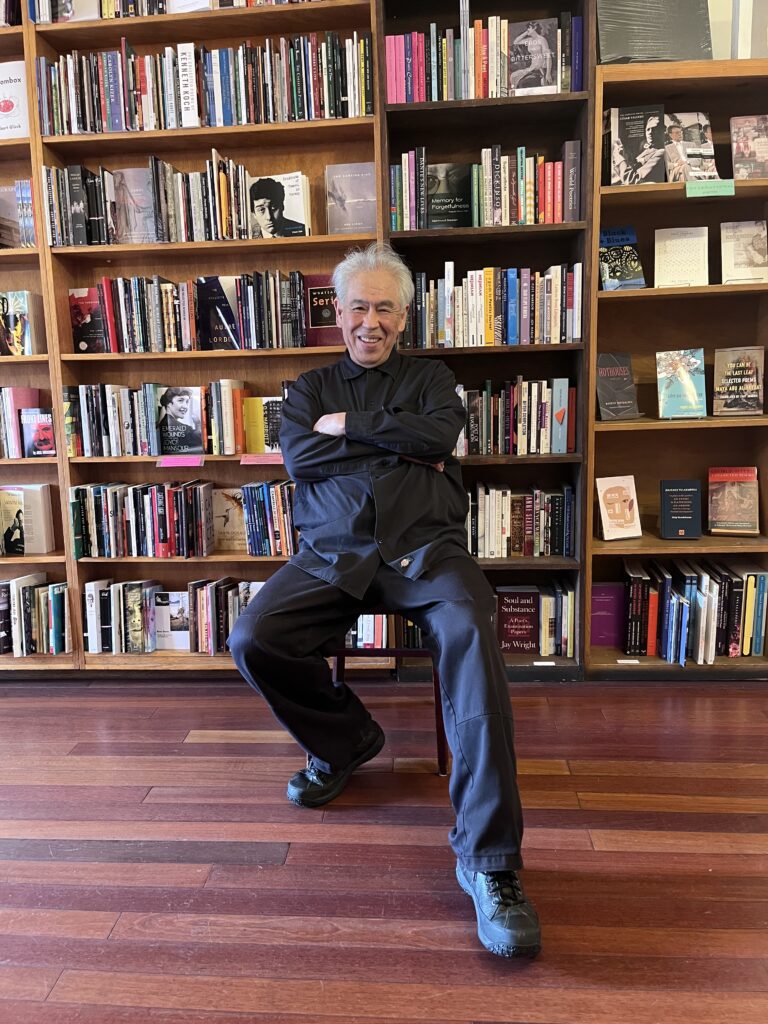

Courtesy of Stacey Lewis / City Lights.

Paul Yamazaki has been City Lights Bookstore’s chief buyer for over fifty years, responsible for filling the shelves of the San Francisco shop with the diverse range of titles that make City Lights one of the most beloved independent bookstores in the United States. Founded by Lawrence Ferlinghetti in 1953 and once a hangout for Beat poets, today the bookstore and publisher specializes in poetry, literature in translation, and left-leaning books relating to social justice and political theory. Yamazaki was the recipient of the National Book Foundation’s 2023 Literarian Award for Outstanding Service to the American Literary Community and has mentored generations of booksellers across the United States. This interview was compiled from conversations held between Yamazaki and friends of Chicago’s Seminary Co-op Bookstore.

INTERVIEWER

What a joy it is to be here with you today at City Lights on this foggy Saturday in San Francisco. Walking in the front door, I feel like I instantly know where I am. How do you choose which books to put in the browser’s line of sight, how to signal what the bookstore stands for?

PAUL YAMAZAKI

It’s all about developing a conversation between the books. When they’re placed side by side, they talk to one another. Our goal when you walk in is to make sure that, right away, you see books you haven’t seen in other spaces and you see books you already know, in a slightly disorienting way. Right now I’m looking at Jane Jacobs, Lewis Mumford, and Mike Davis grouped together—what a great party to be invited to.

INTERVIEWER

City Lights was founded here, by Peter Martin and Lawrence Ferlinghetti, as the country’s first all-paperback bookstore, and it maintains a dedication to progressive politics and modern literature. Please describe this eccentric corner building in North Beach.

YAMAZAKI

City Lights, since its inception in 1953, has been at 261 Columbus Avenue, which is at the corner of Columbus and Broadway in the northeast quadrant of San Francisco, at the intersection of three distinct immigrant and migrant communities. To the south is the Chinese community, and to the north, the Italian immigrants established a community. To the east was the international district, which was a community of many types of itinerant professions, including seamen, theatrical performers, saloon keepers, prostitutes, and prospectors of all types. The cultural, class, and racial diversities of these communities contributed to the fact that there was a range of housing types at various affordability levels in the neighborhood, which provided cheap rentals for writers and artists.

The other important institution that was close to City Lights was the San Francisco Art Institute, whose faculty and students were important contributors to the bohemian flavor of this part of San Francisco. Every building on the block between Broadway in the north and Pacific on the south burned to the ground during the 1906 earthquake. Our building, 261 Columbus, was one of the first buildings to be completed in the reconstruction. It’s somewhat hyperbolic to say there isn’t a right angle in the building, but it’s metaphorically so. You’re walking through the same doorways that legends like Allen Ginsberg and Diane di Prima walked through. There’s a resonance there. Imagine this space in 1953—350 square feet, filled with magazines and books and people.

INTERVIEWER

You’ve expanded several times since then.

YAMAZAKI

Yes, City Lights now takes up three floors. It feels bigger than it is. There are eighty feet of frontage with generous window displays; they provide the main rooms with glorious light. We have changed some things, but the feeling is the same. The ceilings are twenty feet high, with tight stairways and exposed brick walls. It’s astounding that we haven’t lost anyone to those staircases over the decades! The lower level is a subterranean world, with alcoves and archways that make it feel like it’s in another century. At one point, that basement was an evangelical church. There’s an iconic photo of Lawrence Ferlinghetti here in front of a twenties sign from the church days—“I am the door.” Serendipitous psychedelia. Originally the ground floor was a travel agency run by two Italian brothers. The space that used to be a separate building next door was a topless barbershop.

INTERVIEWER

What guides your curatorial decisions?

YAMAZAKI

It’s a dynamic process. Each bookseller investigates their own subjectivities and their own responses to the texts while still understanding the context of the institution, how we arrived at this point. For example, people are surprised by the fact that we don’t carry most current bestsellers—we could sell many copies, but from our perspective, they are not consistent with our values.

INTERVIEWER

Instead, you have Fred Moten’s In the Break: The Aesthetics of the Black Radical Tradition on display.

YAMAZAKI

My faith in the reader is profound. Our role is to bring them to a new door, to a new room. We are trying to choose the best of what’s out there. How do we arrive at the best? Reading and conversations with other readers, other booksellers. If a book comes into your hands and you find yourself moved by it, ask, How did this find me? Answers to that question will always be fruitful and will always make you a better bookseller. People presume from our fairly healthy selection of critical theory that we are a highly educated, deeply knowledgeable staff. I can testify that this is not the case. But we are curious.

INTERVIEWER

How many titles are you considering in a given year?

YAMAZAKI

At least fifty thousand. There is no way that we could encompass all of that. Even if we could, it wouldn’t lead to a very interesting bookstore. I’ve been at state bookstores in Beijing, and they do that, and it’s fascinating. It’s intimidating, but it leaves it up to the reader to navigate. What we do as booksellers is create an environment where there’s a framework for that sort of navigation. I’m awestruck by buyers of bigger stores like Elliott Bay, which is nearly twenty thousand square feet. I don’t think I could buy for even a five-thousand-square-foot store. I have an almost obsessive quest for excellence in detail and execution.

INTERVIEWER

What are the factors that go into the buying decisions you make?

YAMAZAKI

For a buyer in a store, I think it’s helpful trying to envision where a book will be in the store: How is it going to fit on your shelves? Will it be face out, spine out? Will you display one copy, five copies? How many linear feet do you have to fill in the particular area where it belongs? Our most conventional shelving is poetry—A to Z—but almost everything else is distinctive, not just in naming, but in how the books are in conversation with each other. Should we arrange it regionally, break continents down by country? There are many legitimate approaches. What we excel at is that we are able to have this shimmering conversation. You can only put in thirty-three thousand titles. We carry 1.3 copies per title. It is so easy to get into a backlist buying frenzy and make it very tight to shelve. That section is already at 120 percent capacity. My colleagues are ready to kill me because it takes them ten minutes to shelve two books.

INTERVIEWER

And you have to be mindful of the browser’s experience when the shelves are that tightly stocked.

YAMAZAKI

Because there are so few face-outs, you have to be willing to explore, to invest time and curiosity, and hopefully you’ll be able to come back and start to get a sense: when you see a colophon for a certain publisher, does that excite you? Is there a conversation happening in this section which intrigues you? You’ll be able to create your own personal library in this bookstore that is forever changing. It will be part of a constantly shifting display. The surface of the ocean always looks the same. If you look at it closely, it’s always changing.

INTERVIEWER

Do you think in terms of what will help keep the store in business?

YAMAZAKI

You develop an internal map of measurements. I like to compare what we do to preindustrial navigators. We’ve always said, “I have a feeling about this, a feeling about that,” but now we’re combining our micro-observations with a bit of empirical knowledge. Now you can look at productivity per linear foot. We need to explore strategies for becoming fiscally sustainable while recognizing that the real goal is to guide our readers to a more expansive horizon. If you offer that portal, even if their initial impression might be that what you’re recommending is arcane or dense or difficult, if your assessment of the book is accurate, you will find a reader—not just a reader but a delighted reader.

INTERVIEWER

City Lights has taken notable risks in publishing, famously putting out Allen Ginsberg’s Howl and Other Poems in 1956.

YAMAZAKI

A poem like “Howl” puts complexity directly in our faces. It’s hard to put ourselves back sixty-seven years ago to see the level of courage that Allen had to write that poem and put himself out there. And for Lawrence to publish it. It’s still a challenging poem, all these years later. We’ve never been looking for comfort.

INTERVIEWER

Is that generative discomfort part of City Lights’s legacy?

YAMAZAKI

If we look at the streams of art and literature through the three hundred years of the development of capitalism, our task is to challenge those notions of authority, to challenge those strictures. The artists who have brought points of vision and beacons of hope within a capitalist system have always been problematic. The challenge to the reader, then, is how to parse all of that? How to develop your standards of aesthetics and morality? I feel very strongly that those cannot be received, they must be developed.

INTERVIEWER

Looking around the store, I wonder which books mean the most to you? Which ones do you go back to again and again?

YAMAZAKI

The Man Without Qualities I’ve started at least two times, but I never got past 750 pages. The book I reread the most is Moby-Dick. I would love to reread Karen Tei Yamashita’s novel I Hotel. Karen is one of the most gifted writers of this century. She never approaches a story the same way, which is one of the reasons, I think, that she’s not better known. I Hotel is ten novellas, each approached in a different way and yet each of them still tells the story of a small group of Asian American radicals in the late sixties. Of really significant books written in the twenty-first century, I think it is one of the most underread.

INTERVIEWER

Why do bookstores matter?

YAMAZAKI

We are about the process of discovery. There has never been a year where there hasn’t been something that has threatened our existence as an industry or made life as booksellers challenging. Some of the most exciting and challenging bookstores are no longer with us. I’m thinking of Midnight Special in Los Angeles, St. Mark’s Bookshop in New York, Hungry Mind in Saint Paul, Minnesota, and Cody’s Books in Berkeley. Not to be able to go to those stores any longer, at least in my topography, makes the world much smaller.

Three Lives in the West Village of New York City and the Green Arcade in the Hub neighborhood of San Francisco were the two jewel-box bookstores that bracket the continent. They were both wonderfully expansive and deep—Three Lives still is!—despite what many of us would think of as confining spaces of six hundred to eight hundred square feet.

INTERVIEWER

And yet we’ve also seen a lot of stores open in recent years.

YAMAZAKI

Yes! To see Word Up or Mahogany—or the changes at Point Reyes or East Bay—those are amazing stores that give me hope. Any time I walk into a store that has relatively new leadership I feel delight. Each store has its particular environment. It’s hard to articulate. The world disappears except for those eight hundred square feet. Each store has its own way of embracing you, embracing the reader, and creating a sense of the universe expanding. For anybody curious and interested in printed matter, the more bookstores you go into, the more you’ll realize how many different ways there are to be curious. That helps us set a foundation to be more knowledgeable about the world we inhabit. At a great store you can look at twelve well-selected, serendipitous linear inches and find a universe.

From Reading the Room: A Bookseller’s Tale, to be published by Ode Books in April.