On Asturias’s Men of Maize

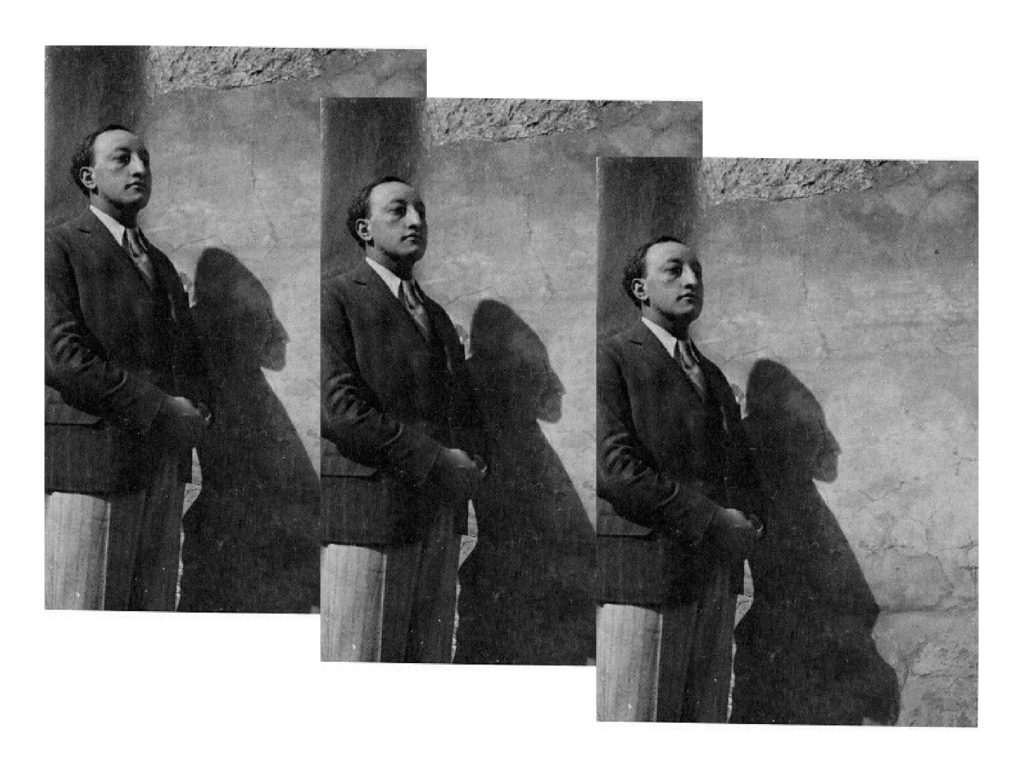

Asturias, ca. 1925. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

For millions of people in the Americas, our Indigenous heritage is something tinged with mystery. We look into a mirror and believe we see the Mayan, the Aztec, or the Apache in our faces. The hint of a high cheekbone; the very loud and obvious statement of our cinnamon or copper skin. We sense a native great-great-grandparent in our squat or long torsos, in the shape of our eyes, in our gait, and in the emotions and the spirits that drift over us at times of joy and loss. But the particulars of our Indigeneity, the weighty and grounded facts of it, have been erased from our history.

In my Guatemalan-immigrant childhood, the great Mayan jungle city of Tikal was a symbol of the civilization in our blood. Despite the humility of our present in seventies Los Angeles—my mother was a store cashier, my father a parking-lot valet—we were once an empire. My father suggested that a personal, familial greatness was there in our Mayan heritage, waiting to reawaken. I could not trace who my Mayan forebears were, exactly. But I knew the Maya were in me because I was a guatemalteco; or, in the hyphenated ethnic nomenclature of the time, a “Guatemalan-American.” Only now do I realize how deeply fraught the idea of being “Guatemalan” truly is. “Guatemala” is a way of glossing over the cultural collisions and the racial violence that produced a country centered in the mountain jungles and river valleys where Mayan peoples ruled themselves until Europeans came.

Men of Maize is Miguel Ángel Asturias’s Mayan masterpiece, his Indigenous Ulysses, a deep dive into the forces that made and kept the Maya a subservient caste, and the perpetual resistance that kept Guatemala’s many Mayan cultures alive and resilient. Like most people born in Guatemala, Asturias more than likely had some Indigenous ancestors, even though his father, a judge, was among the minority of Guatemalans who could trace their Spanish heritage to the seventeenth century. When the dictatorship of Manuel Estrada Cabrera (later the subject of Asturias’s novel Mr. President) sent the future author’s father and family into an internal exile in the Mayan‑centric world of provincial Alta Verapaz, the young Miguel Ángel fell deep into the great well of Indigenous culture for the first time.

In the 1920s, Asturias left for Paris to study. Soon he would become a member of a generation of Latin American thinkers influenced by the Eurocentric aesthetics and worldviews of the time: modernism, surrealism, socialism. In his own artistic practice, these ideas would fuse with the Indigenous spirituality and consciousness of the Americas. The life stories and the mythology of common Mayan and “mixed” folk of Guatemala would appear in his work, and influence it, again and again. In Men of Maize, he rejected the superficiality and sentimentality to be found in so many works about Indigenous cultures written by outsiders. The Mayan families in the novel are not hapless, helpless victims living out one tragedy after another in the face of the relentless march of modernity. Instead, in a frenzy of surreal stories and images, their ghosts and folktales and visions take over the narrative. Darkness comes streaming out of an anthill. A postman transforms into a coyote. Fire sweeps across the corn‑covered landscape, both as a tool of ruthless capitalism and as an agent of peasant retribution. In this fashion, Asturias reimagined the birth of Guatemala as a mad, disorderly event that unleashed countless personal and familial passions: betrayal, mourning, love, loyalty, and revenge.

It’s more than a little ironic that winning the Nobel Prize in 1967 made Asturias a symbol of national pride in Guatemala. By then, the writer had fled the country to escape the military dictatorship brought to power in a 1954 CIA‑backed coup. In the decades that followed, Guatemala’s elites assimilated Mayan Indigeneity into a soft‑focus narrative about the country’s national identity. Guatemala’s tourism ministry, Inguat, produced countless posters for airports and travel agencies depicting Mayan temples and stelae, and Indigenous women dressed in traditional textiles. In this “official” story, the nation’s Indigeneity was something colorful and harmless, a commodity to market to cash‑spending Europeans and norteamericanos.

My parents were in their mid‑twenties and living in Los Angeles when Asturias won the Nobel. For my father, especially, the writer’s triumph became yet another symbol of our inherent Guatemalan greatness. When we drove through Mexico on a family trip to Guatemala a few years later, he stopped somewhere along the way and bought several of his books. I remember, vividly, the beautiful woodcuts of their paperback covers, produced by the Argentine publisher Losada. On the cover for Hombres de maíz, a yellow face with enormous eyes stared out from behind black cornstalks. But I could not read that book, or any of the other Asturias books my father brought home. They were in Spanish, a language that was slowly dying in my U.S.‑educated brain.

When I returned to Guatemala in the eighties as a college educated, Spanish‑fluent adult, I mimicked Asturias’s artistic practice and began to collect the oral histories of my relatives. (Asturias’s first book, Legends of Guatemala, begins with the epigraph “For my mother, who used to tell me stories.”) I had my first grown‑up conversations with my maternal grandfather and my paternal grandmother, both people of striking Indigenous features. My grandfather had been born in Tecpán, Guatemala, a center of the Kaqchikel Maya; and my grandmother was from Huehuetenango, the capital of Guatemala’s Mayan north‑west frontier, the city and nearby villages home to the Mam, K’iche’, and other peoples. I asked them both the question so many young Latino people want to ask their elders: What are we? To what tribe or nation do we belong? Both answered: “No, we’re Spanish.” We were not Indian, they insisted, despite all the evidence to the contrary.

At the end of the twentieth century, it was still taboo for a person of “mixed” heritage to embrace their Mayan identity. Among the “Ladinos” (as the mixed population of Guatemala call themselves), Indigeneity remained associated with backwardness and passivity. “Indio” was an insult equivalent to “stupid.” These racist ideas endured despite all the books Asturias had written. Despite Mulata de Tal and Leyendas de Guatemala. Despite Men of Maize. Despite the shining gold medal handed to him by the Swedish Academy.

Four years after his father’s Nobel, Rodrigo Asturias, the novelist’s oldest son, founded a leftist guerrilla movement. He took as a nom de guerre the name of a character from the opening chapter of Men of Maize: Gaspar Ilom, the leader who resists the encroachment of outsiders on Indigenous lands. In the seventies and eighties, the Gaspar Ilom who was inspired by a fictional character built a real‑life army whose ranks grew to include legions of Mayan fighters. On the same trip to Guatemala on which I pressed my grandparents about our Indigenous heritage, I traveled through the countryside and saw bombed bridges and rebel graffiti—the calling cards of that largely Indigenous guerrilla army. What I saw inspired a scene in my first novel, The Tattooed Soldier, a book that tackled the legacy of the genocidal war that the Guatemalan government launched against a Mayan rebellion.

When I finally read Men of Maize, I saw echoes of my family story in every chapter. My grandfather had told me of a days‑long walk he undertook as a young man, sleeping in the town squares with other travelers along the way. In Asturias’s novel I read of “rivulets of local folk” on the highways, “their bedding stored away in cane baskets” so that they, too, could sleep along the road. Asturias describes a shaman’s ritual to induce “spider‑spells” that involves the sprinkling of red pinole powder, flour, and tortilla crumbs on a straw mat; I have a vague memory of being a boy and my mother taking me to see a woman doing something very similar. Soon I understood that our family’s Indigeneity was not a great black hole of mystery, but rather something alive and very real inside of me. In my memories, in our way of being.

Men of Maize describes the birth of a new people. Or, put another way, it describes the journey of an ancient people into a new age. A time when they don Western clothes and marvel at the miraculous interventions of their non‑Western deities in a Spanish‑speaking world. When they live and mix with German and Chinese immigrants and Americans and assorted other “whites,” and when they have adventures alongside these new peoples. In villages and towns that are as Mayan as they are European, in the hills and jungles and valleys of a country called Guatemala. I can see now what Asturias discovered a century ago: that “Guatemala” is a synonym for mixing.

From the foreword to Men of Maize by Miguel Ángel Asturias, to be published by Penguin Classics in September.

Héctor Tobar is a Pulitzer Prize–winning journalist, a novelist, and a professor at the University of California, Irvine. His books include Our Migrant Souls, the New York Times bestseller Deep Down Dark, and The Barbarian Nurseries.