How to Plant and Grow Virginia Creeper

Parthenocissus quinquefolia

Virginia creeper, Parthenocissus quinquefolia, is a fast-growing native vine in the Vitaceae or grape family.

Also known as woodbine and five-fingered ivy, this species is common in the eastern United States and Mexico. The leaves change to a variety of colors in the fall, and wild birds are attracted to the berries.

Note however that the deep blue, berry-like fruits contain oxalate crystals that are highly poisonous to people and pets. Also, the sap may irritate broken skin and cause it to blister, so this plant should be handled carefully.

We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission.

And make no mistake – this perennial is aggressive. Unchecked, it may become invasive in the garden.

In this article, we discuss Virginia creeper’s potential merits and let you decide if it’s right for your landscape.

Here’s what we’ll cover:

What You’ll Learn

Let’s get started.

What Is Virginia Creeper?

P. quinquefolia is a self-clinging, climbing vine. The Latin “Parthenos” means “virgin,” for Queen Elizabeth I and the state named after her. The second part, “cissus,” is a variation of the Latin term for ivy, “kissos.” “Quinquefolia” means five-leaved.

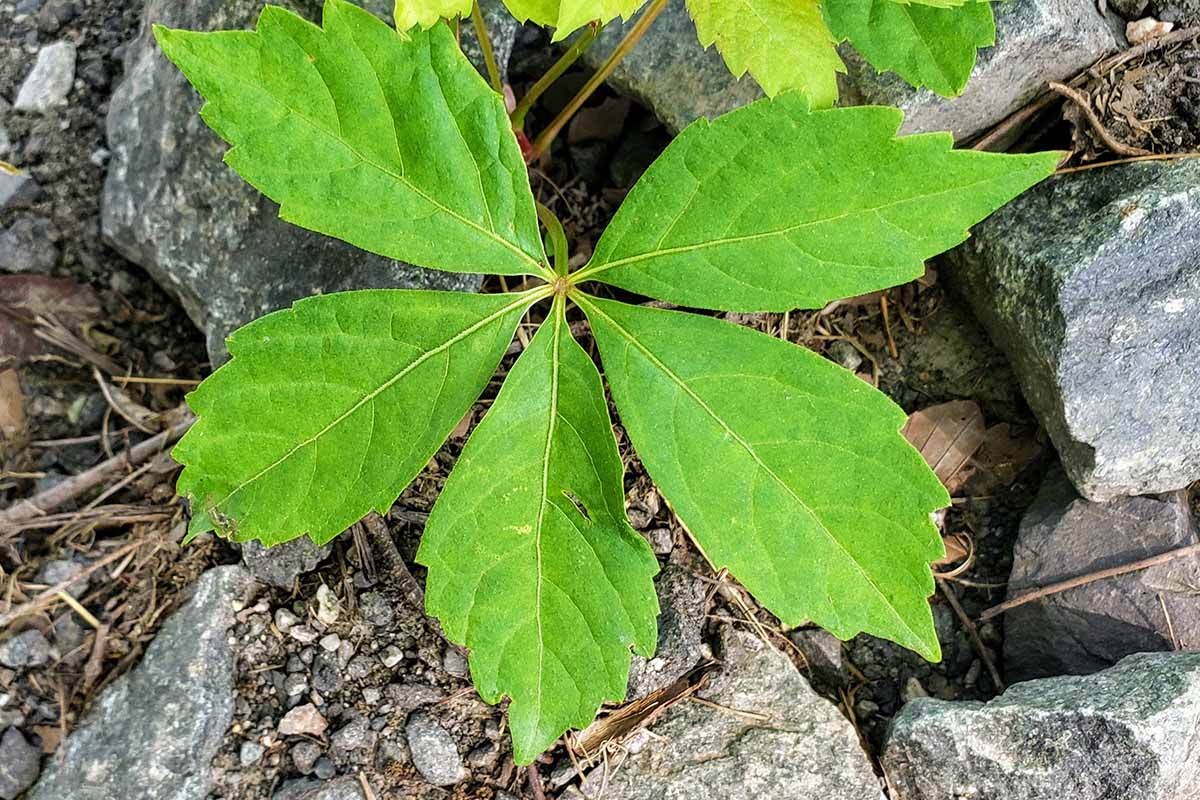

The leaves are compound, consisting of five lobes arranged like fingers on a hand, in what is known as palmate fashion. They are green and serrated, bronzing to purple, red, or yellow in the fall.

The five lobes make it easy to distinguish from three-leaved poison ivy, Toxicodendron radicans. However, sometimes there are only three lobes, making it hard to distinguish the plants.

Nondescript whitish-green flowers bloom in late spring to early summer, after which green berry-like fruits appear. They mature to deep blue and attract foraging songbirds.

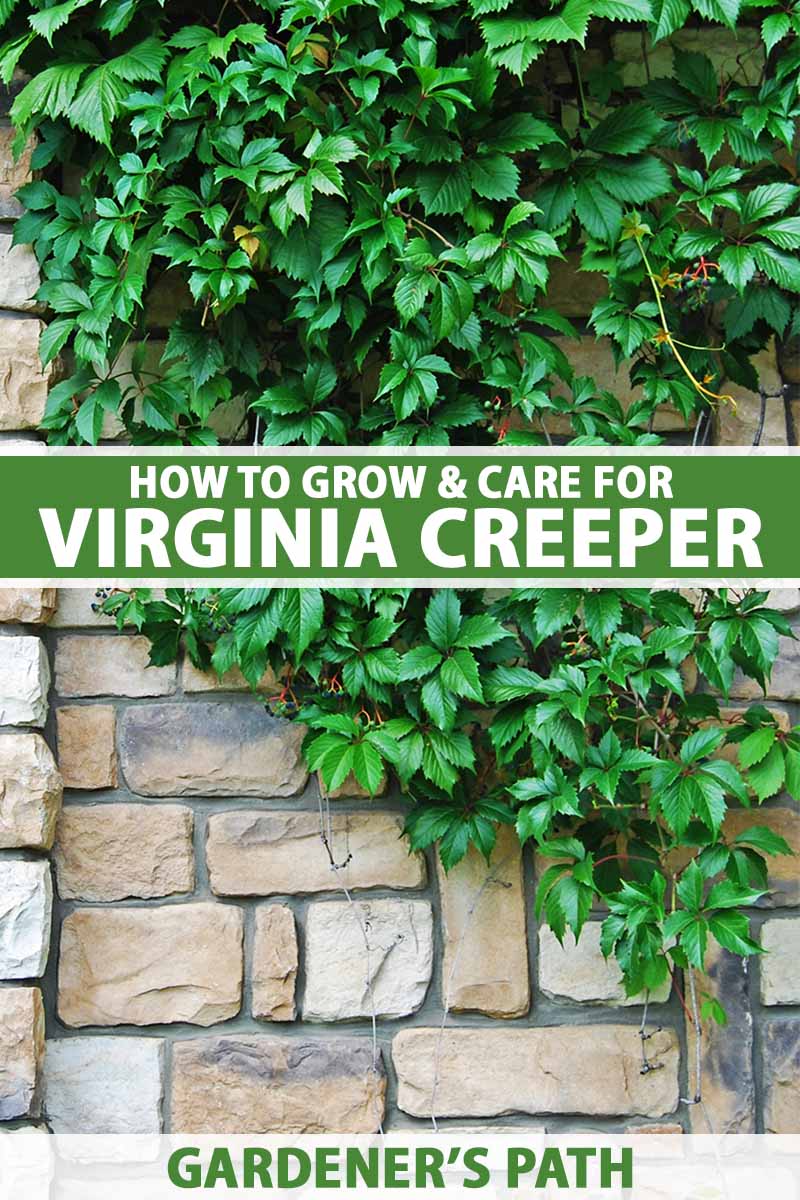

As the stems grow, they reach for something to cling to, often wrapping around objects in their path. Unchecked, they can strangle other plants.

The growing tips of the stems or tendrils have sucker disks that adhere to surfaces with a sticky mucilage, making it difficult to remove them from porous surfaces.

As they creep over ground soil, the stems sprout adventitious or aerial roots that anchor them to the ground.

Cultivation and History

Woodbine is featured in gardens as an ornamental type of flora that thrives in USDA Hardiness Zones 3 to 9.

It rapidly sprawls over fences, ground, rocks, tree trunks, and utility poles. In one year alone, it’s not uncommon for a vine to put on 20 feet of new growth. Mature lengths average 30 to 50 feet but may reach 100 feet.

Cultural requirements include soil of average quality, a pH of 5.0 to 7.5, and good drainage. The plants tolerate clay soil, provided it is not so compact that it doesn’t drain. Standing water is likely to cause rotting.

Historically, native Cherokee and Iroquois healers used Virginia creeper to treat various ailments, including jaundice, sumac poisoning, diarrhea, inflammation, lockjaw, and urinary infections.

Despite its aggressive nature, P. quinquefolia is prized by many, not just for its vibrant fall color and appeal to local wildlife but its ability to withstand air pollution, salt, compacted soil, and excessive heat.

In addition, deer don’t generally seek it out when there is other foliage to nibble.

Propagation

Start with seeds, cuttings, or nursery plants to grow Virginia creeper.

Here’s how:

From Seed

Winter chilling is necessary for seeds to germinate. Sow them outdoors in the fall for sprouts the following spring.

Alternatively, you can provide artificial cold stratification.

About eight weeks before the last average frost date in the spring, place the seeds in a zippered plastic bag with moist vermiculite or potting medium.

Store the bag in the refrigerator.

After eight weeks of chilling, remove the seeds.

“Scarify” the seeds by rubbing them lightly with a nail file and placing them in water overnight to open the seed casings and jump-start germination.

Choose a sunny location and sow the seeds outdoors at a depth of three-eighths of an inch.

Maintain even moisture and avoid oversaturation.

Starting with seeds is not the easiest method, as germination rates are often low.

Also, I don’t recommend starting seeds indoors in seed-starter cells, as we do with many plants, because transplanting the fragile seedlings creates further opportunities for failure to thrive.

Instead, consider the following methods for taking cuttings from existing plants. Perhaps you have a friend who will share theirs with you.

From Soft Stem Cuttings

In the spring, cut a length of stem from the growing tip that is five inches long.

Use clean pruners to slice through the stem just below a leaf node. Ideally, there will be several leaf nodes on the stem.

Snip off the leaves from the bottom three inches so you have a leafless lower stem.

Place the stem in a clear container that contains three inches of water.

Place the container in a location with bright indirect sunlight. Change the water daily.

When roots sprout, transplant the cutting to the garden. Plant it one to two inches deep to completely cover the roots.

Alternatively, dip the bare stem into rooting hormone powder and place it directly into the garden soil at the same depth.

From Hard Stem Cuttings

In late fall to early spring, when the vine is dormant and leafless, select a woody stem with multiple leaf nodes. Cut a five-inch length just below a leaf node.

Fill a six-inch biodegradable seed starter pot three-quarters full of potting medium.

Dip the stem into rooting hormone and place it two to three inches deep in the potting medium.

Tamp the soil firmly around it and water well.

Place the pot in indirect sunlight.

Keep the soil evenly moist but not soggy.

After the danger of spring frost passes, transplant the entire seed-starter pot into the garden with the rim even with the ground soil surface.

Tamp the soil around it and water well.

If you don’t want to start with seeds, and don’t have a friend with a vine, you can purchase a plant from a nursery.

Transplanting a Nursery Plant

Whether it’s a little “start,” with a soft stem and few leaves, or a well-established specimen with creeping tendrils and ample foliage, the method for planting is the same.

The key is to maintain the same depth in the ground as it was in the pot, to avoid transplant shock.

Once settled in the soil, tamp around it and water well.

And finally, if you have vines of your own, you can easily root additional plants with the following method.

By Tip Layering

Tip layering is the process of taking a growing stem and anchoring it to the ground to grow roots and become a separate plant.

In the summer, choose a vine to direct toward the ground. If necessary, use a rock to hold the vine in place.

Examine the stem and locate one or more leaf nodes about six inches from the growing tip.

Rough up the soil beneath one of the leaf nodes to mound it up. Push the leaf node into the mound of soil.

Remove the rock you were using to hold the stem down, and place the rock on the leaf node in the soil mound.

Water weekly if it doesn’t rain.

Allow at least two weeks for roots to sprout from the leaf node, maybe more.

When you lift the rock and find the stem is attached to the ground, it’s time to separate it from the rest of the vine.

Cut the vine about six inches away from the rooted tip to release it.

Use a shovel to unearth the rooted stem tip, dirt and all.

Plant the newly rooted vine at the same depth it was during the rooting process.

Now that we know how to propagate a vine, let’s find out how to give it a good start in the garden.

How to Grow

Whether you start with seeds, cuttings, or tip layers, or purchase a plant from a nursery, you’ll need to choose a part- to full sun location. Plants tolerate deep shade, but the brighter it is, the prettier the fall foliage will be.

While P. quinquefolia is not fussy about soil conditions and tolerates compacted earth, you should still work the ground to a crumbly consistency to a depth of at least six inches before planting for good drainage. Pooling water may lead to root rot.

Allow 10 feet between seeds or plants for a mature spread of five to 10 feet. Good airflow helps to prevent fungal diseases.

Always tamp the soil gently over seeds or around plants and water well.

During the first growing season, provide an inch of supplemental water each week if it doesn’t rain. Because this species has exceptional drought tolerance, you may not have to water after the first year.

Fertilizer is unnecessary due to the species’ natural vigor.

Growing Tips

With a plant this easy to grow, success is almost a sure thing when you remember to:

- Provide a full sun location for the best fall color.

- Grow in soil that drains well.

- Space plants according to mature dimensions to support airflow and inhibit fungal conditions.

- Sow seeds at 3/8 of an inch and set plants at the same depth they were in their original setting.

- Provide an inch of water per week in the first year.

- Avoid overwatering to prevent the roots from rotting.

Pruning and Maintenance

When you plant Virginia creeper where it doesn’t interfere with other flora, pruning chores may be minimal.

For broken stems or those ravaged by pests or disease, cut back to a point just above a leaf node to support healthy new growth. Discard infected or infested material in the trash.

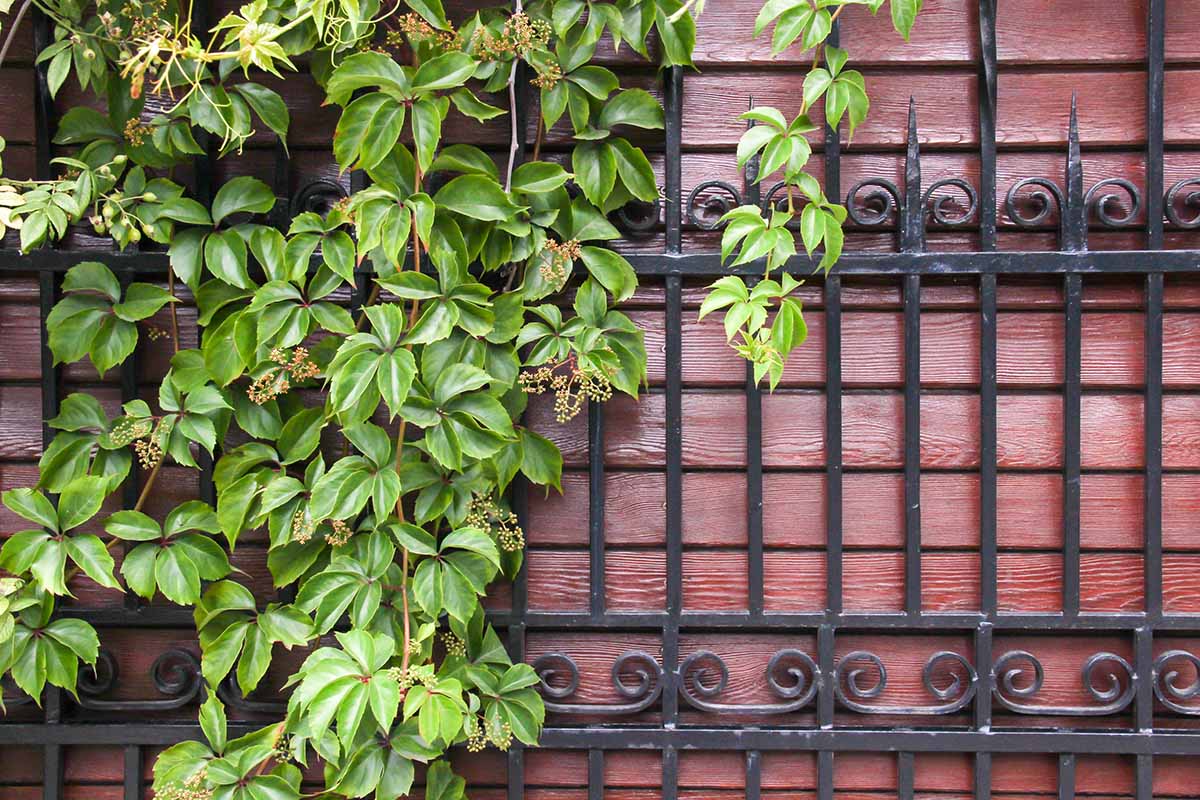

As a plant matures, you can guide it in the direction of your choice. Use garden twine to train it around a fence or trellis as desired.

Beware that vines become woodier, thicker, and heavier each year if unpruned.

I once grew a pretty creeper on my back garden fence. Novice that I was, I planted bee balm and daylilies a little too close and spent a few growing seasons unwrapping vines from my flowers’ throats.

And while the scarlet fall foliage and blue berries were gorgeous in the fall, keeping up with unwanted growth was time-consuming.

As the vine aged, the main stem became woody. In early spring, to reign in growth, I used a pruning saw to cut the entire vine down to a length of about six inches. That slowed things down a bit.

However, even with regular pruning, beware that the base of the stem will become hard and bark-covered like a tree trunk, and if you decide to remove the plant, you’ll have to dig out a substantial stump and roots.

Cultivars to Select

There are cultivated varieties of Virginia creeper available that offer features like a smaller stature, variations in fall color, reduced leaf size, and a more modest growth rate.

Here are a few to consider:

Engelman

P. quinquefolia ‘Engelmannii’, aka Engleman ivy, is similar to the native species, with its 30- to 50-foot height.

However, it has slightly smaller leaves and is somewhat less aggressive than its endemic counterpart, although it possesses an even better ability to cling to surfaces.

Autumn leaves form a burgundy backdrop that showcases the deep-blue berries.

Engelman is available from Nature Hills Nursery.

Monham

Star Showers® P. quinquefolia ‘Monham’ is a variegated variety with cream-colored leaves speckled with green and swaths of solid green.

In the fall, the leaves retain their variegation even as they shade to pink. Vines typically reach lengths of 20 to 35 feet.

Troki

Like the native species, Red Wall® P. quinquefolia ‘Troki’ reaches mature heights of 30 to 50 feet tall and widths of five to 10 feet.

The foliage of this type is bronze in springtime, shades to green during the summer, and bursts into shades of scarlet in the fall. You can be sure birds will flock to the beloved deep-blue berries for a spectacular autumn display.

Red Wall® ‘Troki’ is available from Nature Hills Nursery.

Yellow Wall

P. quinquefolia ‘Yellow Wall’ has a slightly smaller reach than the native species, attaining heights of 20 to 30 feet.

However, instead of shading to purple or red, the leaves burst into bold yellow upon autumn’s arrival, magnificently contrasting with the deep-blue berries foraging songbirds crave.

‘Yellow Wall’ is available from Nature Hills Nursery.

Keep in mind that planting vines on or too close to buildings may result in sucker damage to exterior surfaces, woody stems and roots may undermine foundations, and tendrils may choke foundation plantings.

Managing Pests and Disease

Per the USDA, P. quinquefolia is not prone to pests or diseases, and those that may affect it may not do extensive damage.

The sphinx moth caterpillar, Eumorpha pandorus, may feed on Virginia creeper foliage.

However, the following are defoliating pests to watch out for:

- Beetles

- Caterpillars

- Leafhoppers

- Scale

Infestations generally respond to organic neem oil, an insecticidal and fungicidal treatment that may also be of use in addressing several types of diseases, including:

- Canker

- Leaf Spots

- Mildew

Powdery mildew is the most likely type of fungal condition. Avoid it by planting in full sun, spacing plants well, and not overwatering.

Overall, this is a hardy species, even with some chewed or mildewed foliage. Affected portions can be pruned away, and tossed in the trash.

Best Uses

While aggressive and likely to take the paint off finished surfaces and penetrate masonry crevices with its clinging suckers, Virginia creeper is a native plant that appeals to local wildlife and may benefit your landscape.

Do you have an unsightly stump that is taking its time rotting away? This fast-growing vine provides a lush green camouflage.

Is there a rusting chain-link fence at the back of your property that’s great for containing your dog but ugly to see? With P. quinquefolia, you can create a living wall of foliage for an attractive backdrop to foreground plantings.

To adorn a wall, or grow vines on your house, consider installing an armature, like lattice or a trellis, to keep the suckers from marring and penetrating.

Direct contact may cause damage to painted and even masonry surfaces and may penetrate cracks.

If you have an area of the garden that tends to erode, plant a ground cover of vines to help retain soil.

And don’t forget to consider drought-tolerant native Virginia creeper for water-wise xeriscaping.

With its exemplary shade and salt tolerance, planting opportunities are varied, ranging from woodland to shoreline. However, while it’s not on the invasive species list, Virginia creeper is aggressive and may pose challenges, so plant it with caution.

Quick Reference Growing Guide

| Plant Type: | Perennial vine | Flower / Foliage Color: | Nondescript whitish-green, blue berries/green, burgundy, pink, scarlet, yellow, variegated |

| Native to: | Eastern United States, Mexico | Maintenance | Moderate |

| Hardiness (USDA Zone): | 3-9 | Tolerance: | Air pollution, clay soil, drought, juglone, heat, heavy shade, salt, sand, soil compaction, some deer resistance |

| Bloom Time: | Late spring to early summer | Soil Type: | Average |

| Exposure: | Full sun, part shade | Soil pH: | 5.0-7.5 |

| Spacing: | 5-10 feet | Soil Drainage: | Well-draining |

| Planting Depth: | 3/8 inch (seeds), same depth as container (transplants) | Attracts: | Foraging rodents, songbirds |

| Height: | 30-50 feet | Uses: | Camouflage for stumps; covering for fences, masonry walls, trellises; erosion control, ground cover |

| Spread: | 5-10 feet | Order: | Vitales |

| Water Needs: | Moderate | Family: | Vitaceae |

| Growth Rate: | Fast | Genus: | Parthenocissus |

| Common Pests and Diseases: | Beetles, caterpillars, leafhoppers, scale; canker, leaf spots, mildews (powdery) | Species: | Quinquefolia |

Not for Everyone

Even native vines may sometimes become invasive unless they are constrained. And even then, this species may damage surfaces and other plants in their path.

However, Virginia creeper may be precisely what you need, if you have a non-porous surface, like a chain-link fence, or wish to cover a landscape eyesore, like a stump.

If you choose to plant P. quinquefolia or a cultivated variety, give it plenty of room. Monitor its growth and prune hard as needed to control rampant growth.

And while it may not be every gardener’s cup of tea, the fall color in full-sun locations is so spectacular that you may decide the effort is well worth it.

If you enjoyed this article and would like to learn more about ornamental vines, we recommend the following: