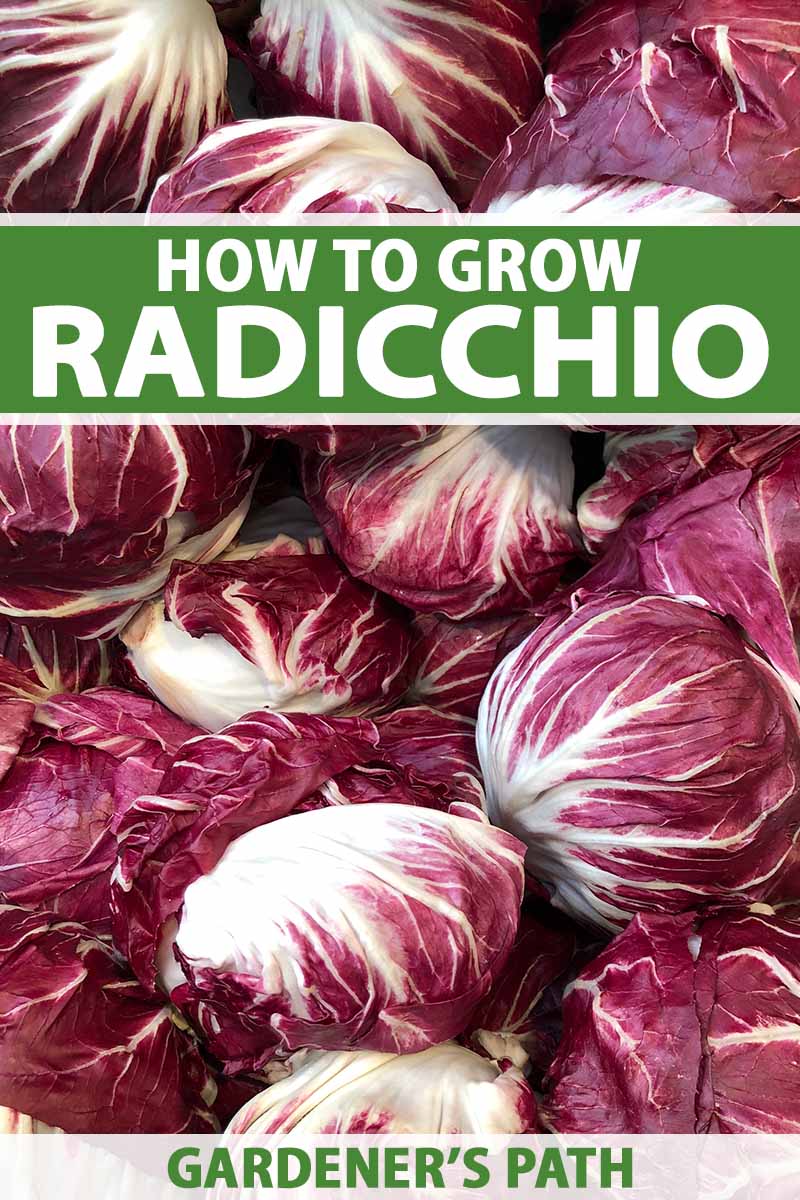

How to Grow Radicchio in the Garden

Cichorium intybus var. foliosum

More than once, I’ve chatted with a friend who has picked up a head of radicchio thinking it was perhaps a tiny red cabbage.

Or maybe they nabbed one at the farmers market on a whim and then didn’t know what to do with it.

I don’t blame my American pals. Radicchio hasn’t gotten its due in the States. I suspect that’s because of its distinctly bitter flavor.

For those who were raised on iceberg lettuce, biting into the leaves can be a bit of a surprise. But in other parts of the world, it’s appreciated for its complex, herbal, and – yes – bitter flavor.

In Italy, growers have mastered the art of breeding the plants over decades. And the production of certain types is considered an art form.

For example, a special heirloom variety known as radicchio rosso di Treviso IGP tardivo is grown in unique conditions, cut down at a specific time, and blanched in a dark location to force a second round of uniquely tender growth.

The IGP stands for Indicazione Geografica Protetta, or Indication of Geographic Protection, to indicate that the quality of this special vegetable is linked to the place where it is produced.

While home gardeners might not be able to produce an exact replica of this carefully produced Italian variety, those of us who can’t get our hands on the good stuff straight from the homeland can at least attempt to recreate this culinary brilliance in our own gardens.

Chefs and home cooks put the leaves in everything from risotto to soup, or they might simply drizzle them with high-quality olive oil before serving.

Even if you don’t love bitter flavors now, once you learn how to grow and prepare these pretty plants, I think you might learn to appreciate their complexity.

On top of that, there’s nothing quite like figuring out how to take advantage of those months when everyone else’s garden is being tucked in for the winter, or just waking up in the spring.

I suspect October, November, March, and April aren’t highlighted on many northern growers’ calendars as prime gardening time.

Sure, you can push your lettuce, cabbage, and leeks past their normal season with some smart season-extending techniques and equipment like cold frames and frost blankets. But who wants to go to all that effort?

If you live in USDA Hardiness Zone 4 or above, growing radicchio may be the answer.

I feel so clever serving up my freshly harvested goodies to my neighbors while the snow is falling outside, long after they’ve tossed their last tomato plant into the compost. And you will, too.

Succeeding with these plants is all about timing, as these veggies are a bit fussy about temperature and water. But once you know exactly what they need, I have no doubt that you’ll succeed.

Curious about what you’re in for? Good! Here’s what we’ll cover:

What You’ll Learn

What Is Radicchio?

Also known as Italian chicory, radicchio (pronounced rah-DEEK-ee-oh) is a cultivated variety of the wild chicory plant, Cichorium intybus.

It is a member of the Asteraceae family, which also includes sunflowers and dandelions.

In Italy, foragers search the countryside for tender young chicory greens, while the cultivated versions are revered by chefs.

If you’re curious to learn about radicchio’s parent plant, we have a whole guide on how to grow chicory.

Radicchio is high in vitamins B9 (folate), C, E, and K, as well as anthocyanins, flavonoid pigments that lend many varieties of this vegetable its purple color.

This plant is actually a biennial, but it’s often treated as an annual and harvested in its first year of growth. Left to its own devices, it will bloom in its second year, go to seed, and die.

Many of the heirloom varieties are named after towns in the Veneto region of northeastern Italy where they were first cultivated.

Chioggia is the most common type found in the United States, and is easy to identify because it looks like a small red cabbage, with a spherical shape.

If you’re thinking that Chioggia is also a type of beet, you’re right! They were developed by growers in the same town on the coast of Italy.

Cultivation and History

In its uncultivated, wild form, chicory has been spread across the world from Australia and Africa to Europe, Asia, and the Americas, carried by both humans and animals.

And over the years, chicory was refined and cultivated by plant breeders into the domesticated versions we know today.

If you’re looking for an exact date, it’s not clear when wild chicory was finally bred into the lovely cultivated red radicchio that you can pick up from the grocer or grow in your garden today.

But the technique of blanching this food crop may have started in the fifteenth century in the Veneto region of Italy, when a farmer forgot a pile of chicory post-harvest.

After pulling away the rotted covering, he was said to have found the tender, protected, and still delicious leaves inside.

Another legend credits Italian farm workers with discovering the process of forcing chicory heads when they placed the harvested vegetables under straw mattresses for protection from freezing temperatures, while others claim it was the French.

Perhaps the most often repeated tale related to this practice suggests the red Treviso radicchio so revered across the world was first introduced when a gardener named Francesco Van den Borre was hired to remodel the gardens of the Villa Palazzi Taverna, a historic mansion in Milan, in the late 1850s.

Allegedly, Van den Borre intentionally grew locally sourced chicory greens with the familiar method of blanching that was already used to produce Belgian endive.

Whatever the reality is, this process has been refined and perfected in various regions of Italy for generations.

Today, to produce radicchio rosso di Treviso IGP tardivo, the plants are harvested in autumn, roots and all. This is done after the first frost, but before it gets too cold.

The growers want the roots to stay intact so the plants can produce a second round of growth.

After cleaning off the soil and removing the outer leaves, the heads are bound together and placed in vats of cold running water for a few weeks, in the dark.

The main root begins growing again and new, tender leaves in shades of white and ruby red emerge in the center.

The root is cleaned and shaved to be used separately, and the vegetable that remains is the world-famous treat that is prized in Italy. It has a vibrant red color, and is less bitter than other chicories.

If you’re lucky, you can sometimes find this variety outside of Italy, but make sure it’s the real thing by looking for the EU’s IGP designation.

Propagation

Radicchio can be propagated by seed or from transplants. However you decide to grow yours, most varieties will do best with eight inches of space between plants, and 12 inches between rows.

Spacing adequately is important because it encourages proper airflow, an important preventive measure that can help to prevent disease.

But some experts will advise against spacing radicchio too far apart, claiming a bit of crowding can actually help to encourage the heads to develop the ideal shape.

From Seed

You may sow seeds in the ground in the spring, three to four weeks before the average last frost date in your area.

If you choose to plant in the fall instead, your goal is to sow the seeds so they will mature about four weeks after the first frost.

Find the expected number of days your selected cultivar requires to mature, and then determine the first average frost date in your area to calculate your planting date.

Most cultivars mature in an average of five to six weeks., and seeds will typically germinate in about a week.

Not every seed is going to germinate, so plant a few seeds 1/4 inch deep in each spot, and then thin them out as they start to mature.

It’s always best with leafy plants to gently pluck away the smaller seedlings after they’ve formed one set of true leaves, being careful not to disturb the roots of the others.

If you want to harvest your own seeds for planting, you’ll need to leave a plant from last season in the ground and let it come back the next year. It will bolt, flower, and then go to seed.

Just keep in mind that if you have any chicory relatives growing in close proximity, they can cross-pollinate.

If you wish to start your seeds indoors, put a few seeds in each cell of a seed starting tray filled with a soilless seed starting medium, and plant them to a depth of about 1/4 inch.

Keep the planting medium moist until they sprout, and then thin them so the strongest seedling in each cell remains.

From Seedlings/Transplanting

Put transplants in the ground in the spring right around the time of the last average frost date in your region. A surprise frost won’t hurt them.

For a fall planting, check your seed packet to determine the time to maturity for your chosen cultivar, and aim for a harvest date that is about a month after the last frost date.

If you’ve started your own seedlings indoors, be sure to harden them off for a week or so before planting them out in their permanent spot.

To do this, bring the container outside for one hour on the first day and leave it in a partially shaded spot.

The next day, leave it outside an hour longer and let it get a little bit of sun. Keep adding an hour each day until the plants are outdoors for seven or more hours at a stretch.

When you’re ready to put them in the ground, dig a hole slightly larger than the container each seedling was growing in, and put them in the prepared soil.

Then, gently fill in around the plugs and water well.

How to Grow

These leafy plants need full sun or partial shade to grow best. If you live in a warmer climate, ensure they have partial shade during the hottest part of the day.

As they grow, some types turn from green to red, while others start out red, and some stay green. This can be impacted by the amount of sun they are exposed to.

The most important thing to know is that heat is radicchio’s enemy. When air temperatures climb above 75°F, chances are high that your plant will bolt, or growth will be stunted.

On the other hand, temps below freezing all the way down to 20°F won’t hurt your crops.

That’s why most people grow theirs in the fall or spring. But if you live somewhere that stays cool all summer, such as the Pacific Northwest, you can grow these plants all season long if you choose varieties that are a bit more heat tolerant.

Radicchio also needs moist soil. If you let your plants dry out, they’ll turn bitter, they may bolt, and growth could be slowed.

Imagine a well-wrung out sponge. That’s how wet your soil should be at all times. The roots shouldn’t sit in water, and they shouldn’t dry out either.

This generally translates to an inch or two of water each week, depending how much rain you get. Not sure? A rain gauge can help!

Radicchio can tolerate a range of soil types, but loamy, fertile earth is best. Water retention and good drainage are key. If you don’t have the right kind of soil naturally, amend your soil with compost or sand.

Weed control is an important element of growing radicchio, and it’s important to note that these plants can’t compete with weeds.

After you’ve put them in the ground, add a two-inch layer of organic mulch such as leaves or grass to help retain water and to suppress weeds as well.

Side dress plants with a nitrogen-rich fertilizer a month after planting.

Blood meal is a reliable option, and you can find it from Down to Earth at Arbico Organics. Don’t fertilize after the heads start to form.

Head out regularly to check on their progress, monitor moisture levels, and dig up any unwelcome plants that appear in the vegetable patch.

Container Growing

You can also always grow your plants in a container filled with a high quality potting soil if you don’t want to fuss with amending the earth and fighting weeds in your garden.

Soil Mender has a good option, which you can pick up at Arbico Organics.

Use a container that is at least eight inches wide and deep, and that has at least one half-inch drainage hole in the bottom. You don’t want the soil to become waterlogged.

Speaking of which, keep an eye on the water level, since these plants are sensitive to drought, and containers tend to dry out faster than the ground. Mulch can help with this if you’re planting in pots too.

Forcing and Blanching

Whether you call it forcing, blanching, bleaching, or whitening, some types of chicory plants benefit from this extra step if your aim is to produce a crop with the most crisp texture and complex flavor.

Similar to the way celery is often produced, or white asparagus, preventing your plants from producing chlorophyll prior to harvest is key.

The tightly packed inner leaves that result when growing red varieties of radicchio in this way are typically more vibrant in color as well, and special varieties produced in particular areas of Italy are known as a delicacy.

Non-forcing or self-blanching types of radicchio are also available for home growers who would prefer to skip this part and get straight to enjoying their harvest.

Experts in these age-old traditions would argue that the tradeoff here is a significant loss in quality.

To force radicchio, growers may opt to leave the plants in the ground for a period after a hard freeze, either with or without tying the outer leaves closed around the heads first, or covering each one with a pot or some other type of opaque container.

After harvest, simply pull away the dead outer leaves to find the tender hearts inside.

You could also cover the plants with straw for a few weeks towards the end of the growing season, to block sunlight prior to harvest.

Another option is to cut away the initial growth that each head has produced about one inch above the crown, shaping it carefully. (Don’t toss those leaves – they might be a bit more bitter, but you can still technically enjoy them grilled or in a salad.)

Then dig up each plant, roots and all, and wrap the lot in burlap or newspaper.

Place the package in a cool, dark spot with a temperature that is constantly above freezing but below 50°F. These will form new, tighter heads with sweeter leaves within a few weeks.

Professional growers may also force their crops to produce this second flush of growth with the roots submerged in water, or in nutrient-rich sand.

Growing Tips

- Plant in full sun, but remember temperatures above 75°F can cause plants to bolt.

- Mulch to keep the soil moist and to suppress weeds, which can compete with plants for nutrients and harbor disease.

- Some types require forcing, so pay attention to the requirements of your selected variety.

Cultivars to Select

You can generally group radicchio into two types: red heading, and green heading. Some reds only turn that color in cool weather.

And without blanching, some red types may actually take on more of a brown hue prior to harvest, due to photosynthesis.

They can be further divided by shape, with chioggia types being round, like a small head of cabbage.

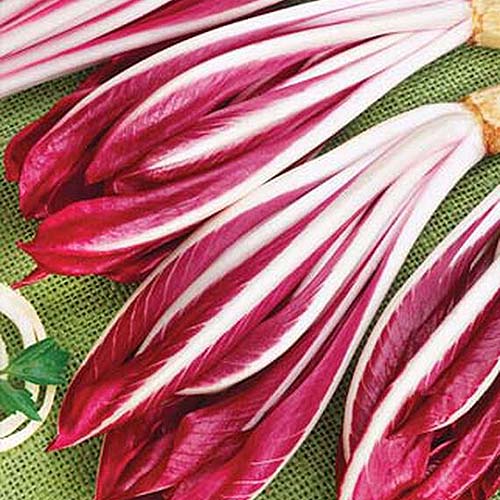

Treviso is elongated, and looks kind of like a Belgian endive that has been dyed red. In fact, you’ll sometimes see this variety of radicchio called red endive.

Radichetta is a loose leaf type, and it’s sometimes categorized separately from head-forming varieties.

There are also forcing and non-forcing cultivars, as mentioned above. Those in the former category require some form of cultivation in darkness prior to harvest to form a tight, crisp head, while non-forcing types may be grown naturally, without additional input.

Bel Fiore

‘Bel Fiore’ means beautiful flower in italian, and you can see why it was given this name.

Instead of forming a compact head, it is more open and loose, resembling a flower with white ribs, creamy coloring, and reddish-pink variegated spots.

The flavor is quite mild, and this type is ready to harvest in a mere 52 days.

You can force this type, but the loose heads are also delicious just as they are.

Chioggia

Also called ‘Variegata di Chioggia,’ this red and white variety is a non-forcing, round headed type. It naturally has a tight, compact shape, and can grow to be as large as a head of cabbage.

The tender, thin leaves are extremely bitter and are ready to harvest in 75 days.

Indigo

‘Indigo’ is a non-forcing hybrid variety that matures in 65 days, It’s resistant to rot and is more tolerant of heat than most other types.

It has a round head and burgundy coloring that develops delicious flavor even in the absence of a cold snap, and vibrant color without blanching.

Palla Rossa

This is a non-forcing type with dark green exterior leaves, and red leaves with white ribs on the interior.

It has a slightly round shape, but with slightly elongated leaves, sort of like an egg. It matures in 90 days and can handle a little extra heat.

You can find seeds available from True Leaf Market.

Red Verona

Also known as ‘Rouge de Verona’ or ‘Rossa di Verona,’ this variety has a round, cabbage-like shape and is ready for harvest in 90 days.

It’s particularly suited to fall harvesting, but watch out – it might bolt on you if you plant it too early in the fall or too late in the spring, since it is sensitive to heat.

Note that this is a forcing type, so you’ll need to do a little extra work for your harvest. But the results will be worth it!

You can find packets of 500 seeds available at Burpee.

Red Treviso

‘Red Treviso’ is an heirloom variety, closely related to ‘Early Treviso.’ Both are valued in Italy as classic ingredients with a long history.

Opting for this variety is the closest you’ll be able to get to growing the famed ‘Rosso di Treviso’ at home.

Forcing is required to get the best slender shape and vibrant red color, and the leaves are known to be less bitter than those of other cultivars.

Ready to harvest in 60 to 80 days, you can pick up a packet of seeds at Burpee.

Rosso Di Chioggia

This is a compact, round heirloom type that matures in just 70 days. It has a lovely deep red color with bright white ribs.

There is also a variegated variety available, which has unique burgundy and white variegated leaves. It’s a forcing variety, but it’s worth the effort if you seek tasty, picture-perfect results.

Managing Pests and Disease

As much as I’d love to say that you can just set and forget radicchio, you’ll probably end up facing some kind of pest or disease issue at some point.

While that’s true of most plants, radicchio can be particularly susceptible. If you want your crop to make it to harvest, keep an eye out for these common issues.

Herbivores

Radicchio is delicious, and humans aren’t the only ones that think so. You’re going to have to fight off some mammals, as well.

Deer

Deer like to eat radicchio and all types of chicory, but it might not be the flavor that they’re after.

A study by N. M. Schreurset et al of the Institute of Veterinary, Animal, and Biomedical Sciences at Massey University in Palmerston North, New Zealand found that chicories could reduce populations of internal parasites in ungulates.

Regardless of their motivation, you’ll need to protect your garden with fencing, row covers, or other deterrents if deer are a problem in your area.

Rabbits

Rabbits will take a nibble of your radicchio if they get the chance. Use raised beds, fencing, or any of the other techniques we recommend in our guide on how to repel rabbits from the garden.

Voles

Voles apparently love radicchio. I say “apparently” because who knows what’s really going through their tiny rodent minds. Maybe their moms told them to diversify their diets?

Anyway, my neighbor claims they prefer these bitter greens over just about anything else. To that I’ve gotta say, at least they have good taste.

Voles dig little freeway systems just under the surface of the soil that they use to travel to food sources. Unlike moles, they don’t leave behind mounds of dirt as they dig.

Controlling voles usually takes a multi-pronged approach, including good garden hygiene and not planting crops too close together. Add to that fencing, repellants, or live traps and you can likely save your harvest.

St. Gabriel Organics’ Holey Moley Mole Repellent

St. Gabriel Organics’ Holey Moley granular repellent can be spread wherever voles travel.

Insects

Insects not only attack plants, but they can spread diseases as well. Here are the most common ones to watch for.

Aphids

Sometimes I feel like standing in the garden with a fist raised in the air as I shout, “Curse you aphids!”

It’s irrational, but sometimes it’s the little things that make you feel better when you’re fighting a seemingly never-ending battle with bugs.

Aphids suck. Literally. They suck the life out of your plants, and they can spread bacteria and attract mold too.

Fortunately they aren’t that challenging to deal with – which is good, because if there is one guarantee in gardening, it’s that you’ll have to battle aphids at some point.

Chicories are usually attacked by green peach aphids (Myzus perisicae), lettuce aphids (Nasonovia ribisnigri), and plum aphids (Brachycaudus helichrysi), but there are other varieties out there that may go after your crops as well.

All of them are tiny and oval and they come in a variety of colors, including pink, yellow, green, red, black, or brown.

Blast them off your plants with a spray of water from the hose and prune away the outer leaves. Applying reflective silver mulch around your plants can help to deter these sap-suckers.

Insecticides aren’t usually necessary, but you might need to resort to an application of neem oil if things get bad.

Bonide makes a reliable option that I’ve always had good results using.

Mix it with water and spray it on any infested plants.

You can get some at Arbico Organics.

Cabbage Loopers

Cabbage loopers (Trichoplusia ni) are green caterpillars that inch along leaves, nibbling as they go.

Look for ragged holes in the leaves of your plants.

The easiest way to deal with them is to hand pick them off the foliage. You can also use Bacillus thuringiensis, a natural form of pest control.

Mix it with water and spray it on plants and the soil.

Monterey Bt is an effective product, which you can purchase from Amazon.

Flea Beetles

Flea beetles (Epitrix spp. and Phyllotreta spp.) are so named because they leap away when you approach, just like the pests that love to attack Fido.

They’re tiny black or brown insects, shiny or sometimes metallic in appearance, with or without an orange stripe.

They nibble little shotholes in the foliage, which can stunt growth. Older plants are usually able to survive an attack.

Floating row covers should be your first line of defense, and they can help to ward off other types of pests as well. Lay covers over your rows and secure the sides in the soil.

Neem oil is an effective treatment, but you’ll need to be sure to reapply every few weeks throughout the growing season.

Leafminers

Leafminers (Liriomyza spp.) are actually kind of cool in that they’re tiny worms that chew interesting zig-zagging, maze-like tunnels into the foliage of plants. The problem is that you also want to eat those leaves, so you’re going to have to get rid of them.

If you are patient, you can go outside and press along any tunnels that you find to smash the miners to death. But that’s not going to be feasible if you have a lot of plants.

Instead, encourage or purchase beneficial insects, like Diglyphus isaea wasps. These tiny wasps lay their eggs in leafminer larvae, paralyzing them. When the eggs hatch, the wasps consume the leafminer host.

You can purchase these parasitic wasps in quantities of 250, 500, or 1,000 from Arbico Organics.

You can also apply neem oil regularly if the pests are present.

Slugs

Slugs are never ideal garden visitors, but when they’re attacking edible plants that you prize solely for their foliage, they’re really the worst.

They’ll begin by nibbling a few leaves, but left to their own devices, they can rapidly consume an entire head.

Handpick them off plants in the evening and put slug traps out in your garden. You can make your own or purchase them.

To make one, choose a steep-sided glass and bury it in the garden near your plants, up to the rim. Fill it 3/4 of the way with beer. Then, sit back with a beer yourself and watch the little slimers climb in and drown.

Don’t feel guilty, it’s either them or your radicchio harvest, and we aren’t going to all this trouble for nothing, right?

Learn more about how to manage snails and slugs in this guide.

Disease

There are a handful of diseases that you need to watch out for, but all of them can be avoided to some degree if you practice crop rotation.

That means not growing plants in the chicory family in the same place more often than once every few years.

You should also water at the soil level rather than sprinkling the leaves of your plants, and make an effort to avoid overcrowding them.

Alternaria Leaf Spot

If your plants have this fungal infection, caused by Alternaria spp., the foliage will develop reddish-brown spots with gray centers. These spots can form on the stems as well, and cause the leaves to wilt.

This type of fungi thrives in wet, humid, hot weather, so if you stick to growing your crop in the cool months as is recommended, you’ll be less likely to come across it.

Good gardening practices like crop rotation and watering at the base of your plants can prevent this disease from taking hold.

If you do encounter a problem, you may need to break out the fungicides. You can treat an infection with a copper fungicide, which is suitable for use up until the day of harvest.

You mix it with water and spray it onto any part of the plant that has been impacted.

Bacterial Leaf Spot

This pesky disease is caused by the bacteria Xanthomonas hortorum and you will notice dark water-soaked spots that form on the leaves of your plants. Over time, the foliage will start to turn yellow.

This type of bacteria thrives in cooler weather, which you can’t avoid if you’re growing radicchio.

There is no cure for leaf spot, so prevention is key. Crop rotation, adequate airflow between plants, and watering at the soil level will all help to prevent an outbreak.

Black Rot

Black rot is another bacterial disease, but unlike leaf spot, the X. campestris pv. campestris bacteria that cause it thrive in warm weather. It also pops up in areas with high humidity.

On leaves, it shows as V-shaped orange lesions that turn dry. After that happens, the leaves will wilt and fall off.

There is no cure for this disease, so do what you can to prevent infection.

Again, good air circulation is important, as are crop rotation, weed control, and watering at the base of plants.

Damping Off

Damping off is extremely common. If you start enough plants from seed, there is no doubt you’ll run into damping off at some point, which is caused by the fungi Pythium spp., Rhizoctonia solani, and Fusarium spp.

It shows up in several ways. Seedlings may fail to emerge, or once they do, they may become thin and yellow or appear water-soaked at the base.

Seedlings may collapse. If they survive through the early stages, the plants will be stunted and won’t ever grow well.

These types of fungi prefer warmer temperatures close to 70°F, soil that is excessively moist, and over-fertilized soil.

Fortunately, there are lots of things you can do to avoid damping off. Always, always, always be sure to clean your containers and tools between uses with a 10 percent bleach solution, and use clean, fresh potting mix or seed-starting soil.

Downy Mildew

This disease is caused by a water mold that is more closely related to algae than fungi. Although there are numerous types of downy mildews, the one that attacks radicchio (and various types of leafy greens) is called Bremia lactucae.

It starts out as fuzzy patches on the underside of the foliage. As time goes by, it starts to move to the upper side of leaves.

At the risk of sounding repetitive, prevention is key. Rotate your crops, water at the soil level, keep weeds away, and be careful to maintain good air circulation. Being an attentive gardener is so important, and worth the effort!

Have you already done all of this and you still find yourself going head-to-head with this common foe?

You can use a copper fungicide to control this disease.

Harvesting and Storage

As the weather heats up, radicchio becomes more bitter. That’s why many people choose to grow it in the fall, so they can avoid the risk of bolting and the flavor changes that may ensue if an unexpected heatwave comes along.

It’s time to harvest when the heads have reached the size recommended on your seed packet. Don’t wait too long, though.

It’s always better to err on the side of harvesting this vegetable early rather than picking it late, because the leaves will rapidly become increasingly bitter as long as the plants remain in the ground.

Give the head a little squeeze. It should have some give but feel firm.

To harvest, separate the heads from the roots by cutting the stem below the leaves with a clean knife. The leaves of the head should stay together.

You can store your harvest in the crisper drawer in the refrigerator in a perforated plastic bag for two to three weeks.

Don’t store radicchio near apples or pears. These fruits release ethylene, which can cause your harvest to develop an even more bitter flavor.

If your plants happen to bolt, you can eat the flowers as well. They taste like common chicory flowers, with a flavor that is something like honey and apple, plus a touch of bitterness. It’s best to harvest the flowers in the morning, when they’re open.

Preserving

Leafy vegetables aren’t exactly the easiest thing to preserve, but it can be done. One option is to make refrigerator pickles.

You can pickle radicchio leaves by packing them loosely into a canning jar. Then combine five parts white vinegar with one part sugar in a saucepan.

Bring the vinegar and sugar mixture to a boil. Meanwhile, you can toast any spices you’d like to add to the mix in a separate pan or in the oven. Try white peppercorns, coriander, juniper berries, or mustard seeds.

Add the toasted spices to the vinegar mixture and pour it over the leaves in the jar, leaving about 1/4 inch of room at the top. Screw the lid on top, and refrigerate for a week or two before digging in.

Like many leafy vegetables, radicchio doesn’t freeze well. It turns soft and mushy in the freezer. You should also aim to eat it sooner rather than later, because the leaves can turn more bitter as they age.

Recipes and Cooking Ideas

Are you one of those people who picks around the little red leaves in salad mixes? Don’t be ashamed, not everyone loves bitter flavors. But I’m going to try to change your mind.

Learn to love bitter flavors? Yes, hear me out! While studies suggest that a preference for bitter flavors is part of our genetic makeup, who hasn’t learned to appreciate a flavor that they might have previously turned their nose up at?

Most kids would rather bite into a Twix bar over a piece of bitter dark chocolate, but many of us learn to love the stuff as we get older. In my opinion, developing a love for radicchio could be just a recipe away, if you’re able to find the right one.

Luckily, radicchio is one of those wonderful ingredients that can be prepared as simply or as intricately as you want, and you can cut the bitterness down a bit with the right balance of other flavors.

If you’re feeling like you don’t want to go to too much trouble, wash and tear the leaves and dress them in a bold and fruity olive oil, along with some salt and pepper. That’s all you need.

You can also dress your basic salad up a little with some walnuts and honey, or make it a tasty grain salad with chewy einkorn berries.

Find the full recipe at our sister site, Foodal.

For a perfect fall salad, combine radicchio, apples, goat cheese, and sunflower seeds. To get all the details, check out the recipe on Foodal.

The leaves are also delicious lightly grilled, which mutes the bitterness a bit.

If you want to get a bit more involved, this recipe for vegan pasta alfredo with sauteed radicchio will knock your socks off. It’s also available from Foodal.

My personal favorite? I had a nibble of a friend’s radicchio salad once at a staple restaurant in Portland, Oregon called Nostrana.

It had a bitter crunch, for sure, but was balanced out by a bit of salty anchovy dressing and parmigiano cheese, topped with buttery garlic croutons.

After the meal, I ran home, still full, and made my best effort at recreating this masterpiece. Here is my version:

Combine one two-ounce tin of anchovies (including their liquid) with 3 tablespoons of white wine vinegar, 3/4 cup fruity olive oil, one small garlic clove, and freshly ground black pepper to taste.

Muddle it together in a bowl. I like to mash everything together with my mortar with a pestle. Then add two tablespoons of capers with the brine. Set aside to let the flavors meld for an hour at room temperature.

Chop up four cups of radicchio into small pieces. This is key. You want tiny bites covered in a rich layer of dressing to balance out the bitterness.

Toss the dressing and the leaves together, and top with slices of parmesan and croutons.

I made sage, rosemary, thyme and garlic croutons out of day-old sourdough bread, but there’s no reason to get so fancy if you’re short on time. Boxed croutons will be just as good.

My best bit of advice when dreaming up ways to use your harvest is to combine the bitter leaves with ingredients that have rich, fatty, or salty flavors.

Sure, you could combine it with something sweet like honey, which will mellow out the bitter bite, but I find that fat and salt really let the bitterness shine without being overpowering.

Quick Reference Growing Guide

| Plant Type: | Leafy biennial vegetable | Maintenance: | Moderate |

| Native To: | Eurasia | Tolerance | Frost |

| Hardiness (USDA Zone): | 4-10 | Soil Type: | Organically rich loam |

| Season: | Spring, fall | Soil pH: | 6.5-8.0 |

| Exposure: | Full sun to part shade | Soil Drainage: | Well-draining |

| Time to Maturity: | 55-90 days, depending on variety | Companion Planting: | Beets, carrots, cucumbers, lettuce, mustards |

| Spacing: | 8 inches between plants, 12 inches between rows | Avoid Planting With: | Beans, peas |

| Planting Depth: | 1/4 inch | Family: | Asteraceae |

| Height: | Up to 12 inches | Genus: | Cichorium |

| Spread: | Up to 12 inches | Species: | intybus |

| Water Needs: | Moderate to high | Variety: | var. foliosum |

| Pests & Diseases: | Deer, rabbits, voles; aphids, cabbage beetles, flea beetles, leafminers, slugs; Alternaria leaf spot, bacterial leaf spot, black rot, damping off, downy mildew |

Ditch the Lettuce and Embrace Chicory

Bitter flavors don’t always get their due, but once you know how to make the most out of radicchio, whether that means forcing the heads or dressing your harvest up right, it’s easy to become a convert and start loving this unique veggie.

Just remember: avoid the heat, stay on top of the water, rotate your crops, and keep those weeds off the scene. If you make the effort, you’ll be enjoying a delicious crop in no time.

Are you growing radicchio? Share your tips in the comments section below!

And don’t forget to check out these growing guides for other types of chicory to grow in your garden:

Photos by Kelli McGrane, Kristine Lofgren, and Raquel Smith © Ask the Experts, LLC. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. See our TOS for more details. Product photos via Arbico Organics, Bonide, Burpee, and True Leaf Market. Uncredited photos: Shutterstock. With additional writing and editing by Allison Sidhu.

The post How to Grow Radicchio in the Garden appeared first on Gardener's Path.