Game, Set, Match: Tennis in the Archive

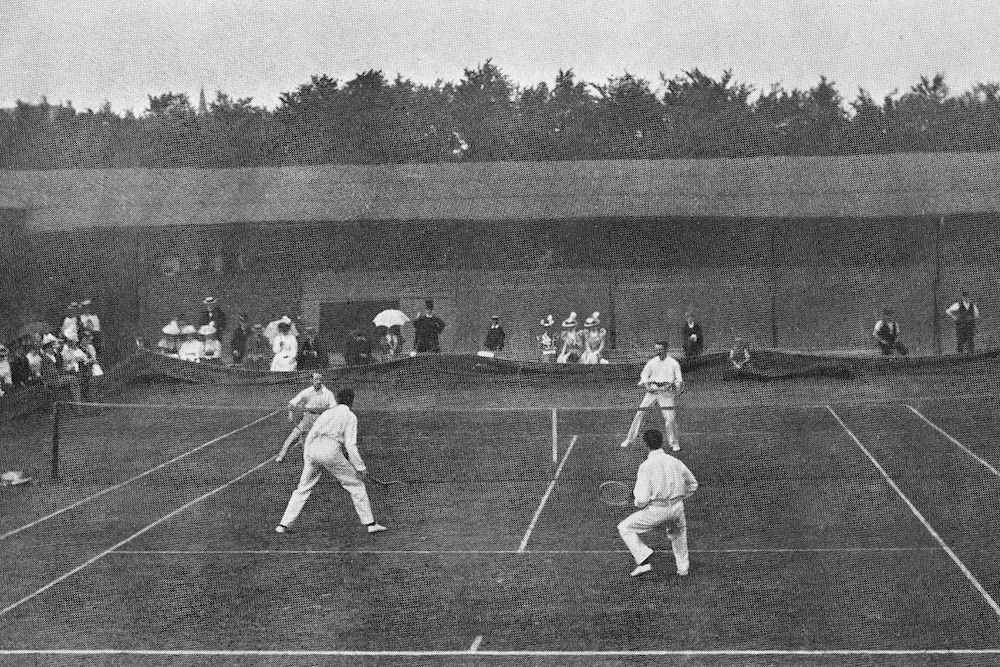

Gentlemen’s Doubles tennis final at the 1897 Wimbledon Championships. Photo: J. Parmley Paret. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

I learned a lot while fact-checking the Summer 2021 issue, and I owe a ton of that knowledge to Joy Katz for her essay “Tennis Is the Opposite of Death: A Proof.” Now, whenever the subject of tennis comes up, I find myself bursting with trivia. Did you know that the first Wimbledon championship was held in 1877, or that the All England Lawn Tennis and Croquet Club employs a Harris’s hawk named Rufus to keep pigeons from interfering with matches, or that Hawk-Eye is the name of the technology used to verify a challenged umpire call? There’s a story in there somewhere. Tennis is well known for drawing the attention of the literary set—Martin Amis, Claudia Rankine, David Foster Wallace, and John Jeremiah Sullivan come to mind—and the archive of The Paris Review boasts a wealth of writing on the subject, the sport often taking the role of the Hawk-Eye—a keen lens through which life’s quick volleys may be slowed, reviewed, and challenged in turn.

In Ross Kenneth Urken’s “1, Love,” a tennis stroke becomes the embodiment of a young boy’s “neurotic, racquet-throwing heart,” with nods to Vladimir Nabokov and Philip Roth along the way:

At its best, my slice backhand follows the flamboyant path of a violin virtuoso’s bow striking the climactic note of a concerto—from above my right shoulder plucked diagonally down to my left shoestring. The ball’s tone is a hollow pok on hard courts and a chalky chh-chh on clay that dies on the second bounce. All these dramatics—mere vestiges of a time when I wanted to impress Angela, my middle school crush.

Louisa Thomas opens “Let It Be Love” by rejecting the schmaltzy application of a popular tennis term:

There’s a T-shirt favored by a certain kind of tennis player that says, “Love means nothing to a tennis player.” It’s a pun that no one, it seems, can resist. The 2010 U.S. Open’s slogan is “It must be love.” Please.

Nick Twemlow eschews sentimental love to tackle a range of tough and tender matters of the heart in his sprawling poem “Attributed to the Harrow Painter”:

When I was twelve,

My tennis coach asked me

To pose for him after practice.

I’m an artist, he told me,

I coach to pay the bills …

“Double Fault” finds A-J Aronstein investigating tennis to “figure out what to pass on (a service motion, a slice backhand, a tennis club, a philosophy)”:

The courts were our family’s livelihood; their quality was a matter of pride for my father. Like a farmer who knows the precise chemical composition of the soil in his fields, he could step out on the courts, sniff the air, and know whether to water them or let them bake in the sun.

Pamela Petro’s “ThunderStick” is titled after and structured around a tennis racket:

It’s not every day you get a box of tennis racquets in the mail. I ripped it open and immediately shook hands with each one.

And Clancy Martin similarly centers his story “An Event in the Stairwell”:

I kept my eyes on the racket. Also on his eyes, because you can anticipate a blow that way. Everyone narrows his eyes and looks where he’s going to hit you before he strikes. This is the first lesson of boxing.

“She promised she’d buy this racket from me. I got this racket special. From my daughter.”

Randy, Emily had told me, had a high school–age daughter who was expected by many people to be the next Serena Williams. She lived with her mother in the Bronx and was sponsored by Puma. I noticed the tennis racket had a broken string. Emily was hiding in the bedroom all this time and had instructed me to tell Randy that she was out. I could not decide whether that was reassuring or suspicious.

In “The Ghost in the Dirt,” Rowan Ricardo Phillips talks clay courts and the forgotten legacy of Georges Henri Gougoltz:

Myth, legend, and truth: they work on their own time and make their own order—they’re brilliant and terrible. This story has never been and will always be about a man’s suicide in the face of crushing financial debt. We’ll get to that. And this story both never was and will always be about Rafael Nadal’s run as the master of clay-court tennis. The two collided, unwittingly, on a warm Sunday afternoon in early June in Paris, 2017, when Nadal once again won the French Open in front of a crowd packed into Court Philippe Chatrier.

To take us out, Scott Korb illustrates the mythic heights of tennis writing in his essay “Stage Struck”:

Sports broadcasters are guiltier these days than sportswriters of the “grand metaphor” approach where tennis is concerned. Following the major tournaments this summer on television, I’ve heard again and again of the history about to be made: Raphael Nadal’s seventh French championship (history made), Djokovic’s career Slam (history not made), Murray’s becoming the first Brit to win Wimbledon since 1936 (nope). Even Federer’s thirty-first birthday was seen as historic, according to a certain fan site: “God is too an imaginative word, rather I would call him a ‘Prophet’ / Someday the prophet will make Tennis the most loved sport, I bet.”

Christopher Notarnicola is a veteran of the U.S. Marine Corps and holds an M.F.A. from Florida Atlantic University. His work was featured in The Best American Essays 2017 and has been published in American Short Fiction, Bellevue Literary Review, Consequence Magazine, Image, North American Review, The Southampton Review, and elsewhere. Find him in Pompano Beach, Florida, and at christophernotarnicola.com.

If you enjoyed the above, don’t forget to subscribe to The Paris Review. In addition to four print issues per year, you’ll also receive complete digital access to our sixty-eight years’ worth of archives. Or, choose our new summer bundle and purchase a year’s worth of The Paris Review and The New York Review of Books for $99 ($50 off the regular price!).