FSA shares how it is using data to monitor food risks

A specialist from the Food Standards Agency (FSA) has revealed how the authority is using data science to identify emerging risks by using a variety of sources and analytics techniques.

The aim is to help develop a picture of the food system, its safety, authenticity, and risks and vulnerabilities, so issues can be better managed.

Speaking at IAFP Europe, Julie Pierce, director of openness, data and digital, said she had to persuade the FSA that putting funds and faith into data was a good idea.

“I started with a narrow question, answered it and then expanded it into other regions and commodities. We started off with the observation on the amount of aflatoxins in figs from Turkey. We noticed a seasonal variation in the number of alerts we were seeing and could determine the weather was impacting on the aflatoxin level,” she said.

“It was a relatively straightforward model that we built but it was relevant to those grappling with the real life issue. It proved to be relatively straightforward to extend the model beyond figs to other commodities like Bolivian Brazil nuts.”

Prediction to manage resources

Pierce said the cost doesn’t have to be high and data systems can be fast.

“Our experience is the cloud services are not hugely expensive. The technology that manages the transport of data around the system is not where the huge cost lies. The cost and time comes from poor data quality and trying to understand the data you are looking at, do I need to invest any time and effort in validating or cleansing collected data? We spend more time at that upfront part of the process than we do on the downstream development of tools.”

Using machine learning and artificial intelligence, the agency has developed tools to identify risky imported food and feed products coming into the country and scan incidents being reported globally.

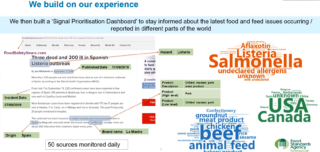

Pierce also spoke about a signal prioritization and a risk likelihood dashboard.

“What we are doing now is trying to see further afield and into the future. From our point of view, having that time to predict and plan for and take action to mitigate any risk is so valuable. We have a system that is collecting data from regulators like ourselves but also other sources like trusted websites, translating it into English and combining it all together into an assessment of the risk we are seeing and presenting that to the user. We update that on a daily basis and speed of response has proven to be really important,” she said.

“The risk likelihood dashboard helps our import team, port health and local authorities trying to determine where the risk is and which commodities should be sampled, when and from where. This has been in operation for a year or so and we are continuing to develop it building on the experience of the data science team and our users as to what they now wish to see. Once you give them some insight it is inevitable they will want more.”

Role in helping local authorities and during pandemic

One proof of concept is helping local authorities prioritize their inspections.

“We used artificial intelligence to build a tool that learns from the past to be able to predict which food establishments at the time of their registration would be likely to be most risky. They don’t necessarily have to have started operating but we can predict with a high degree of accuracy what their likely Food Hygiene Rating Scheme (FHRS) score is going to be. That helps local authorities understand the risk and prioritize the inspections they undertake,” said Pierce.

Some of the approaches and tools were repurposed when the COVID-19 pandemic hit.

“The sorts of questions we were posed just over a year ago now where things like what might happen to the resilience to trade? What was happening in real time for our consumers? We’d been listening to social media for a while for potential norovirus outbreaks but we found we could use the same techniques to listen to consumers voicing concerns around whether or not the virus was conveyed through food packaging and if they should wash their food in bleach,” she said.

“Through the pandemic, as hospitality was closed down, we saw many businesses where still trying to operate but changed their operating model and some new ones started up and came online. It’s often very fast and easy to start selling on a digital platform. But where is that physical shop window to display your FHRS sticker? Are you even visible to the regulators? Yes, you are. You have a digital footprint and we can scan the platforms to see who is operating a food business, we can then check to see whether you are displaying your FHRS online and it is the right rating.”

Example projects

Collaborators include the Food Industry Intelligence Network, Food Standards Scotland, British Retail Consortium, British Meat Processors Association, Red Tractor, and the Food and Drink Federation.

Pierce said the FSA is mindful of the sheer volume of data available across the food system.

“We are starting to work with organizations like FIIN and drawing up a data sharing agreement to see whether or not we can share sampling data the industry are taking and share our data back with the industry. With Red Tractor we’ve been exploring whether the digital remote audit approaches work and if application might be taken forward in the longer term. We’ve used BRC accreditation ratings as a potential input to our ability to segment and understand what is going on in the industry at large beyond individual businesses but trying to group together different parts of the sector.”

“We are starting to work with organizations like FIIN and drawing up a data sharing agreement to see whether or not we can share sampling data the industry are taking and share our data back with the industry. With Red Tractor we’ve been exploring whether the digital remote audit approaches work and if application might be taken forward in the longer term. We’ve used BRC accreditation ratings as a potential input to our ability to segment and understand what is going on in the industry at large beyond individual businesses but trying to group together different parts of the sector.”

The agency has done a number of research projects on IoT, sensors and blockchain.

“The blockchain pilot main learning was the technology was easy but governance was hard. We took that learning into a project on data trusts with the University of Lincoln and the Internet of Food Things building on concepts developed by the Office for Artificial Intelligence and Open Data Institute in the UK,” she said.

“While there is a lot we can do with those smaller datasets, really AI is dependent on access to large comprehensive data and information collected from multiple sources. We see the value when we can link different datasets together. What can we do to ensure the right data is being shared in the right way at the right time?”

The FSA is looking at data trusts for sharing data with different parties in the food system and referred to the work as the Open Ecosystem Federation.

“We are working with HMRC and the Cabinet Office to establish a standard set of tools and protocols that will allow us to share the minimum amount of data to allow each of us to perform our different roles at the border with only the data we need to make the decisions we need to so we are not pulling in all the data about the product as it moves across the border,” said Pierce.

“It’s using chicken imports and we are hoping to prove this approach will work for all participants. Our partners at the University of Lincoln are trialing this approach with the fresh produce industry through a program called Trusted Bytes.”

(To sign up for a free subscription to Food Safety News, click here.)