A Single Enzyme Could Be Behind Some People’s Depression, Scientists Say

For a while now, we’ve known there’s a complex interplay between our hormones, guts, and mental health, but untangling the most relevant connections within our bodies has proved challenging.

New research has found a single enzyme that links all three, and its presence may be responsible for depression in some women during their reproductive years.

Wuhan University medical researcher Di Li and colleagues compared the blood serum of 91 women aged between 18 and 45 years with depression and 98 without. Incredibly, those with depression had almost half the serum levels of estradiol – the primary form of estrogen our bodies use during our fertile years.

The idea that estradiol is related to depression in people with fertile female hormones is over 100 years old. Natural declines in estradiol during menopause and after pregnancy are notoriously linked to negative mood changes.

Other conditions, including polycystic ovary syndrome (where the ovaries produce higher than normal levels of the sex hormones known as androgens, causing reproductive hormones to become unbalanced) and congenital adrenal hyperplasia (a group of genetic disorders where the body lacks one of the enzymes needed to make specific hormones), can also cause low estradiol and depression.

Depression’s link to estradiol likely explains why it’s about twice as common in women than men.

Produced in ovaries and after doing its chores around our bodies – including regulating our menstrual cycles – estradiol is metabolized in the liver and then passed into the gut. Here, the hormone is partially reabsorbed back into the bloodstream to help maintain circulating levels of estrogen.

With this knowledge, the researchers investigated the activities of estradiol in the gut.

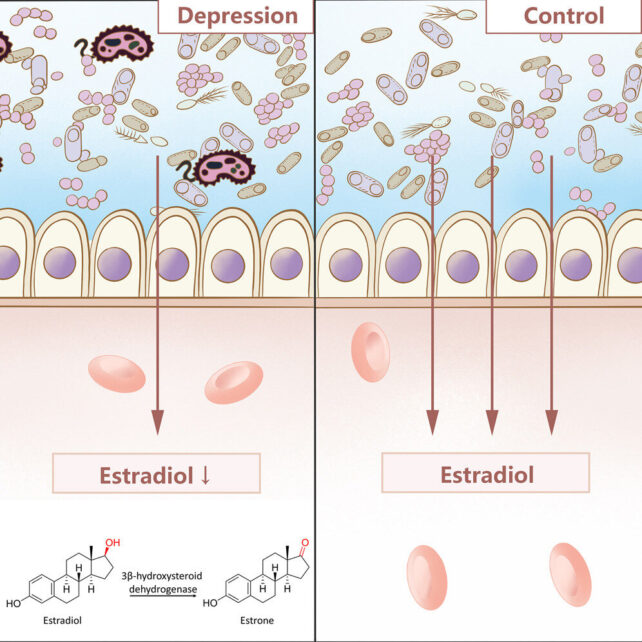

Within 2 hours of adding estradiol to fecal microbiome samples from the women with depression, there was a 78 percent degradation in the hormone. Meanwhile, the tube with microbiome samples from the women without depression only experienced a 20 percent decline in the hormone.

Scientists also transplanted the gut microbiota from 5 of the women with depression into mice, who showed a 25 percent decrease in estradiol levels in their blood serum compared with the mice control group.

It seems clear that a gut microbe is responsible for the increased degradation of this hormone within our digestive systems.

To isolate the microbe responsible, Li and the team placed samples of the microbiome from the women with depression onto an agar plate and provided them with estradiol as their only food source. Two hours later, over 60 percent of the estradiol was degraded into estrone.

White blobs with smooth, hazy edges thrived, and using mass spectrometry, the researchers identified the microbe, a strain of bacteria they labeled Klebsiella aerogenes TS2020.

“These results show that K. aerogenes TS2020 can reduce the serum estradiol level in mice and induce depressive-like behaviors,” the researchers explain in their paper. “Additionally, cefotaxime administration can alleviate such depressive-like behaviors in mice.”

Gene analysis showed that K. aerogenes converts estradiol to estrone with an enzyme called 3β-HSD (3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase). Putting the gene for this enzyme into E. coli and then infecting mice with these bacteria led to the same drop in estradiol and onset of depressive symptoms.

Giving control mice estrone did not increase depressive behavior, ruling out the excess estrone as the problem. Li and colleagues also ruled out other molecules.

The mice with 3β-HSD producing E. coli also had lower estradiol levels in their brains, including in the hippocampus, a brain region known to be heavily involved in depression. Taken together, all this suggests that the microbe-produced enzyme is causing the brain problems.

In a previous study, the researchers identified increased levels of the same enzyme in depressed male patients; the enzyme can also degrade testosterone.

“Taking these two studies together, we speculate that the 3β-HSD enzyme is involved in depression development and that this relationship is sex independent,” the researchers explain.

“We believe that K. aerogenes in feces is not the only gut bacteria that can produce 3β-HSD. Our metagenomic sequencing data showed that the Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron and Clostridia bacterium possess 3β-HSD. However, there may be other 3β-HSD-producing gut bacteria below the detection limit of metagenomic sequencing. Which bacteria can produce 3β-HSD needs further study.”

There has been some focus on estrogen replacement therapy as a possible treatment for depression in women, but if the pathway uncovered here proves accurate, the 3β-HSD producing bacteria could lead to relapses, Li and team caution.

“Estradiol-degrading bacteria in the gut, particularly the enzymes expressed by these bacteria, may be better targets for intervention,” they note.

About 280 million people suffer from depression around the world. For those of us relying on external help with our brain chemistry, better treatment options derived from an understanding of these brain, gut, and hormone connections can’t come soon enough.

This research was published in Cell Metabolism.