The Asteroid Belt: Wreckage of a Destroyed Planet or Something Else?

Just outside the orbit of Mars sits our Sun’s premier collection of space rocks. The asteroid belt has captivated the imaginations of science fiction authors and scientists alike who have considered the possibilities of mining ore, water and other material from the region to boost further space exploration.

But how was this orbiting field of debris formed? Does it represent the rocky bones of a former planet from eons past, or is it a type of gathering place for a planet-to-be?

Scientists have considered both responses as possibilities over the decades. But more recent theories contend that the vast ring of space rocks likely never was a whole planet and is unlikely to be so in the relatively near galactic future. Why? There simply isn’t enough material there.

“This is the cool place in our solar system where all the small bodies go,” says William Bottke, director of Space Studies at the Southwest Research Institute, a nonprofit research and development organization headquartered in San Antonio, Texas.

Former or Future Planet?

Billions of years ago, our solar system was far from being a stable and organized place. Planets were still forming, throwing their neighbor’s orbits out of whack in the process. In light of all this action, some astronomers used to believe a planet that orbited our Sun between the trajectories of Mars and Jupiter was blasted into pieces and formed the asteroid belt that floats in space today.

Scientists thought that “maybe there was a planet there and it got blown to smithereens,” explains Sean Raymond, an astronomer at the Astrophysical Laboratory of Bordeaux, in France. But after researchers began to examine the patterns in iron meteorites that fell to the Earth as meteors, Raymond says, it became clear they didn’t come from one parent body.

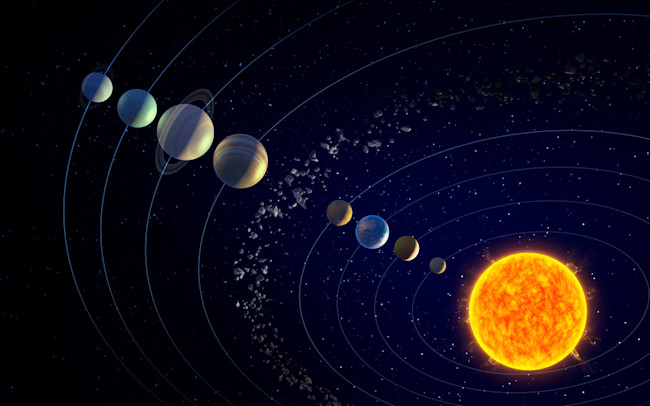

(Credit: Mopic/Shutterstock)

As a result, the thinking began to shift toward the idea that the asteroid belt was full of planetesimals, or pieces of a planet that either hadn’t formed or failed to form. But the trouble with this theory is that there just isn’t enough material in the belt to create such a mass. Ceres is the single largest asteroid in the belt, roughly the size of Australia with a mass nearly half that of all the material of the belt, according to Raymond.

“It’s like tiny little crumbs,” Raymond says.

Cosmic Leftovers

Just because the asteroid belt doesn’t represent the leftovers of a former planet doesn’t mean scientists have abandoned the idea entirely. The belt might have come from parts of other planets that still exist, or be part of a planetesimal — which is like a baby planet — that never completely formed before being smashed apart.

“It used to be kind of a simple story, but in recent years it’s gotten increasingly more complicated as we learn more about planet formation,” Bottke says.

Raymond says that these bits could have been left over from when Jupiter and Saturn were still forming. Later on, these planets may have migrated around the solar system until they eventually reached their present orbits. This would have resulted in a dynamic instability, with chaotic orbits and gravitational forces.

“The solar system of today looks very different from the way it looked 4.5 billion years ago,” Bottke says.

Pieces of Different Puzzles

We now know the asteroid belt doesn’t contain material from a single source. Some of its components may have been derived from the general region of space it currently inhabits. Other material may have come from sources beyond the orbit of Jupiter, Bottke says. Still other asteroids may have arrived from the inner-planets zone, as bits that broke off at some point.

The movements of planets during the solar system’s early period of instability could have resulted in the gravities of Saturn and Jupiter sucking in some material, while sending other asteroids careening into other planets or right out of our solar system entirely. Some researchers even believe that water-rich asteroids banged into Earth in this period, leading to the creation of the oceans we still have today. Raymond says a fraction of these rocks would have been sent off in the right trajectory and speed to join the asteroid belt.

“In that context, we sometimes call the asteroid belt the blood spatter of the solar system,” he says.

Whatever violence may have resulted in sending these bits and pieces to the asteroid belt, the reason they stay put is because Mars and Jupiter’s orbits eventually stabilized. So if an asteroid manages to find its way there, it’s likely not going anywhere, Bottke says.

According to Raymond, the solar system question that most astronomers are concerned with is how the planets formed. The composition of asteroids, their position and their orbits continue to reveal clues about the distant past of the planets.

“Even though we care more about the planets than the asteroids in general, the asteroids are a really good tool for trying to figure out what happened with the planets,” Raymond says. “They’re a really key piece of evidence in that story.”