Repeated Concussions Can Actually Thicken The Skull, New Evidence in Rats Shows

Past research in humans shows that damage to our squishy brain tissue is already done with even just one knock to the head.

But repeated concussions can also thicken the skull bone, according to a new study looking at how multiple head injuries affect rats.

Whereas severe brain injuries can result in skull fractures, in this case, the researchers were interested in how repetitive concussions, a type of mild traumatic brain injury, might deform the bones of the skull.

“We have been ignoring the potential influence of the skull in how concussive impacts can affect the brain,” says Monash University neuroscientist Bridgette Semple, explaining the motivations behind the study.

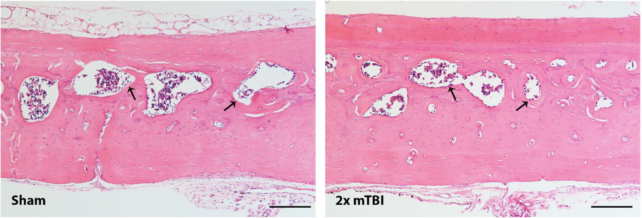

Using high-resolution brain imaging and tissue staining techniques, Semple and colleagues examined structural changes in the skull bones of rats after the animals were dealt either multiple controlled head injuries or a sham treatment that caused no harm.

While the mechanics of concussions – sudden knocks to the head which send the brain ricocheting around the skull – are well studied, the impact on bone growth and structure remains poorly understood.

The team found that repeated concussions spaced 24 hours apart resulted in thicker, denser bones in the skull in close proximity to the injury site. Those changes became more pronounced after 10 weeks compared to 2 weeks post-injury.

The researchers also noted that bone marrow cavities in the skull hollowed out, progressively losing volume from 2 to 10 weeks post-injury. However, the team didn’t measure if the strength of skull bones differed as a result of these changes.

“These new findings highlight that the skull may be an important factor that affects the consequences of repeated concussions for individuals,” Semple says.

Bones, as strong as they may be, are actually malleable living tissues that respond to mechanical forces, hormone levels – even changes in gravity.

Understanding how cranial bones might respond to mild head injuries could complement not just what we know about how concussions damage brain tissue.

It might also shed light on how the meninges (the membranous layers between the skull and the brain) and the skull periosteum (the membrane which covers the outer surface of bones) are impacted, the researchers suggest.

Findings from past research suggest “a complex relationship between bone and brain injury that likely extends beyond responsiveness to the direct mechanical forces applied by a head impact,” write neuroscientist and lead author Larissa Dill of Monash University and colleagues in their paper.

Future studies should consider how the whole head – including the skull, meninges, connective tissues and blood vessels – are impacted, they add.

While a thicker skull might sound like it could shield the brain from further impacts, it’s unclear whether skull thickening is a protective response or a sign of something worse – something which future studies could try to resolve.

“This is a bit of a conundrum,” Semple says. “As we know, repeated concussions can have negative consequences for brain structure and function. Regardless, concussion is never a good thing.”

A recent study found that around one-third of participants who had experienced a ‘mild’ concussion still had symptoms up to eight years later. Imaging studies also suggest that even a single blow to the head could trigger a cascade of cellular damage in brain tissue.

Of course, studies on concussion and how it impacts the brain are limited by what samples researchers can get access to; imaging studies can only tell us so much.

Sportspeople generously donating their brains after death has enabled amassing of valuable ‘brain banks’ that researchers can use to put changes in brain tissue under the microscope, and relate these to symptoms people experience.

Animal studies mimicking concussions can also provide good insight into how the brain responds to trauma, with one recent mouse study finding that head injuries can reconfigure brain-wide neural networks.

But given the host of challenges in studying concussion and subsequent brain damage in people, there’s still a whole lot we don’t know, not least how brain damage after injury manifests differently in men and women.

The researchers behind this latest study note that the time interval between head injuries and the age at which they occur might also affect bone changes, warranting further studies.

“Although there is a scarcity of published literature on skull responses after mild head impacts, cranial bone thickening has previously been reported in the context of hydrocephalus, raising the intriguing possibility that abnormal pressure from cerebrospinal fluid build-up or swelling – as can occur after a TBI – may also act as an intracranial mechanical regulator of bone growth,” in addition to external forces, the researchers write.

The study was published in Scientific Reports.