The Six Pests Plaguing your Fruit Trees — and How to Control them Organically

If you grow fruit, you know you’re creating something delicious when the entire natural world sets its sights on your apples, peaches, and pears. You’re up against a vast and devastating army of insect pests, and if you’re committed to growing organically, conventional sprays and treatments are out of the question. But you’re not powerless in this worthy fight. And you’re not alone.

In this excerpt from The Holistic Orchard, Phillips explains the six most common pests you’re likely to encounter in the organic orchard. You’ll learn what they look like, what they’re after, whether they’re worth fighting at all, and how to do so without disturbing the precious balance of beneficial organisms that make a holistic orchard work.

The following is an excerpt from The Holistic Orchard by Michael Phillips. It has been adapted for the web.

Bugs and More Bugs

Learning to identify who’s who and then zeroing in on the when and where of pest vulnerability (based on family groupings) defines the crux of the matter when it comes to bugs in the orchard. There are some helpful ones and a few deservedly notorious ones, but most species are in truth absolutely innocent. Detailed specifics about the chosen few at your site will be found in the applicable fruit sections and in tree fruit guides listed in the resources. Our immediate goal is to understand how to balance potential pest situations.

Insect consciousness begins with paying attention. Seeing early signs of chewing on the edges of a bud or a light-deflecting pinprick (indicative of a feeding sting or an inserted egg) on developing fruit should put you on alert. Probing for details beyond this first impression leads to finding a tiny caterpillar curled within the sepal leaves at the base of a flower bud or looking for suspected culprits when cool morning dew finds curculios sluggish but not yet in hiding. One grower in Nebraska could not figure what was eating the leaves on his cherry trees . . . until he went out at night with a flashlight and found that june bugs had come up from the ground to feed with abandon. Different things will happen in different places—what’s constant is the need to discern what’s actually going on so you can then take intelligent measures to achieve a happy resolution.

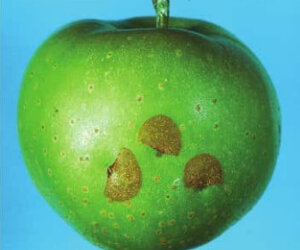

A russeted, fan-shaped scar speaks to the presence of plum curculio in the orchard. The female makes a crescent cut above each inserted egg as a means of preventing fruit cells from crushing her reproductive artistry. Seeing scars on maturing fruit indicates that the apple won the race. Photo courtesy of NYSAES.

Insect injury to fruit offers an important learning opportunity. The ability to distinguish one fruit scar from another more often than not reveals who’s actually behind the deed. Consulting with an experienced grower or Extension adviser, looking at regional pest guides, and perusing the words in this book are all tools for getting your detective credentials in order. Knowing the name of the guilty party—if indeed the damage is significant and thus calls for specific action in the next growing season—leads to learning about the life cycle of a particular pest. This in turn reveals points of vulnerability where trapping, repelling, certain beneficial allies, and specific spray strategies have relevance.

But first let’s do the numbers. You need perspective to know the difference between tolerable damage and a pest situation rapidly ratcheting out of control. Research that tracked the damage done in wild apple trees in Massachusetts over a twenty-year period gives a fairly accurate picture of what’s out there. Plum curculio and apple maggot fly can afflict as much as 90 percent of the fruit in a bad year, with codling moth and one of its close cousins getting digs into about half of these yet again. Additional damage from all other fruit-feeding pests tallies below 10 percent. . . not something to get concerned about by any means. Overmanaging this situation to have all fruit left untouched will have far too great an impact on beneficial populations and thereby induce additional pest challenges. It’s not worth the expense or craziness of doing this. Determine your must-do priorities around those significant pests and grant that a small portion of the crop belongs to the natural world. The concept of balance works both ways.

Who, What, and When

Every insect goes through a molting cycle that starts from the egg. The larval and pupal stages subsequently lead on to adulthood and the reproductive urge. Damage to fruit trees is to either the foliage or the fruit itself. Some of this consists of adult feeding, but more often than not it’s the egg hatching out a very hungry caterpillar or grub. Let’s look at family groupings within the insect world relevant to orcharding as a quick means of getting a handle on potential pest situations.

The goal here is not so much entomological precision as identifying similar patterns to discern possible responses to a pest dynamic deemed unacceptable.

Every fruit grower will experience the orchard moth complex in some form or another. This ubiquitous force can involve dozens of species, but it always means tiny caterpillars munching away on some part of the tree. Internal-feeding larvae go for the seeds in developing fruit, often risking a mere twenty-four hours of vulnerable leaf exposure before getting safely tucked away inside. Look for a small hole in the side of the fruit and often in the calyx end from which orange-brown frass (poop) protrudes. Surface-feeding larvae are content to nibble upon the skin of the fruit, hiding beneath an overarching leaf or where two fruit touch. Many of these are second-generation leaf roller species, which in the spring larval phase were intent on feeding on buds and unfurling leaf tissue. Any resulting fruit damage at this early stage often appears as corky indentations.

Let’s key in on this generational concept, for therein lies both the amplification of the moth problem and the timing of extremely targeted solutions. A given species overwinters as a hard-to-find egg mass, perhaps as larvae (in a dormant state known as diapause), some in a pupal cocoon, and some even as adult moths where mild winters allow for feeding and procreation. Location specifics vary as well, but mostly orchard moths favor laying eggs on leaves and twigs where larvae can subsequently feed. These go on to find some secluded place to pupate: in crevices in the bark, litter on the orchard floor, or sheltered nooks provided by a nearby fence or wall. One way or another, with adult emergence in spring dependent on the development stages still to be achieves, first flight takes place when females get impregnated and then proceed to lay eggs on the new season’s growth. That hatch initiates what is considered to be the first generation of the orchard year – limit this generation and all subsequent generations will be fewer in number. Some species are content with a single round of action, whereas others will achieve as many as five or six generations of egg laying and larval feeding in the extended growing season of warmer climes. The vulnerability points with moths lie in adult attraction around the times of feeding and mating, the need for eggs to respire, larval ingestion and/or contact with biological toxins, and exposing pupae hiding on the tree trunk for physical destruction.

The cherry fruit fly attacks cherries throughout the eastern half of North America. Don’t worry, however – closely related cousins will find the rest of you! Photo courtesy of NYSAES

Fruit-oriented flies affect chosen fruits across the spectrum. Fly larvae are called maggots, which I expect reveals the gruesome scene about to be revealed. The female adult lays her eggs directly into the yielding flesh of ripening fruit, with specific preference by maggot fly species for apple, cherry, blueberry, and so forth. All such fruit becomes a maggoty mess of meandering tunnels and decay. Feeding attractants are used to manipulate adult flies to a deadly meal instead, along with sticky sphere traps that promise the perfect nursery for junior on which to lay an egg. Soil pupation suggests additional vulnerability points. Pick up early drops biweekly to prevent larvae from ever getting into the ground. Spraying the ground beneath badly infested trees with Beauveria bassiana in fall can help reestablish a clean starting gate: These parasitic fungi consume the fly pupae waiting in the soil for next season. Even more deliberately, plant a Dolgo crab tree to draw apple maggot flies in drove…use this as a trap tree to protect other apples, and the apply beneficial nematodes in early fall (the Steinernema feltiae species is recommended for AMF) to seek out the pupae in the ground below.

Sawflies are a different category of critter altogether. Wasp aspects seem to have been incorporated with fly-like behavior in this insect, resulting in a pollinator that in its larval form just happens to bore into developing fruit or strip gooseberry branches of all greenery. Pear slugs (aka pear sawflies) look pretty much like fleshy blobs designed to skeletonize leaves. The vulnerability points here like with sticky card traps, desiccants like insecticidal soap and diatomaceous earth, and knowing precisely when a certain biological toxin will come in contact with apple sawfly larvae moving from a first fruitlet to the next.

The thing about hard-backed beetles is that the majority of these species pupate in the soil. (Those that opt for wood issue will get a separate designation.) Most infamous of all are the curculios, which decimate most any tree fruit in the eastern half of North America. Repellents form the backbone of an organic plan for dealing with these small weevils, with trap trees providing an effective diversion to curtail an otherwise prolonged window of activity. Applicable organic spray options along with ground-level strategies become cost-effective when a species can essentially be funneled to far fewer unprotected trees. More innocuous sorts like earwigs and click beetles contribute back to the ecosystem, reminding me that tolerance has a place. The accompanying sidebar directed at Japanese beetle is this book’s example of taking a particular pest through the biological wringer in order to fully understand what all might be done. Rose chafers are noted for having similar desires for peaches. Out west, look for green fruit beetles emerging from unturned (big clue, right there!) manure pile to wreak havoc on nearby soft fruits.

Green june beetles have an affinity for apples and all stone fruits, whether immature or fully ripe. Feeding damage tends to be sporadic across southeastern states and into the Lower Midwest. Photo courtesy of NYSAES.

We blur species lines in mentioning the unspeakable evil done by fruit tree borers. The reason for lumping certain beetles with certain moths applies across-the-board damage to wood tissue. Grub consumption of cambium and sapwood eventually does in whole trees. Physical inspection and removal involves a great deal of work on your knees with a knife or similar grub-seeking took like a drill spade bit. Some of the moths can be deterred by pheromone trapping, but reducing beetle numbers often involves limiting nearby alternative hosts. Sending an army of parasitic nematodes into badly infested bark tissue by means of mudpack may rectify extreme situations…and even if you lose a favored tree, you may ultimately save others by having eliminated the next round of destruction. Botanical trunk sprays made with pure neem oil are especially promising, acting as an oviposition repellent and adding an element of insect growth inhibition to all such borer wars.

True bugs exhibit an occasional hankering for fruit. These include assorted plant bugs, stink bugs, mullein bugs, apple red bugs, and hawthorn dark bugs. Conventional recommendations for removing the alterative plant habitat for such bugs from the orchard environs go against a diversity plan intended to attract and hold important beneficials. Bug damage often takes the form of a feeding sting, which develops into brownish rough blotches or even outright dimples on the skin of the fruit. Pure neem oil will deter feeding and interrupt the molting cycle on all these guys, which – truthfully – are rarely an all-out force of devastation.

I’ll mention a few insect erratica, as certain regional curveballs can and do show up on occasion. The leaf-curling midge is a tiny fly whose larvae set back young apple tree growth by tightly curling terminal leaves on the ends of shoots. Less photosynthesis means less growth. Red-lumped caterpillars seemingly are Moths from Mars that attack apple, pear, cheery, and quince, defoliating entire branches in just a few days in late summer…Pear thripsattack all deciduous fruit trees by feeding on flower clusters, causing a shriveled, almost scorched appearance if the clusters don’t fall off the tree altogether. Early-season neem oil applications will prevent the majority of thrips invasions. Scale insects are like tree barnacles in that they select permanent feeding sits on branch twigs and limbs. Heavily infested trees appear to be undergoing water stress, with leaves yellowing and dropping. Parasitic wasps often keep scale in check (use a magnifying glass to look for holes drilled through the hard shell of mature scale), so unless you’ve chosen to kill everything in sight, don’t expect much trouble from with San Jose or oystershell scale.

Tarnished plant bug damage to buds and developing fruit is typically minimal – provided these bugs are not pushed up into the fruit trees by exuberant mowing of all nearby ground cover in spring. Photo courtesy of Alan Eaton, University of New Hampshire.

Last but far from least we must give heed to the foliar feeders. Allowing mites, aphids, psylla, and leafhoppers to run amok can set back tree vigor considerably. The good news is that much of this is indeed taken care of by numerous beneficial species given a little time. Commercial orchardists have far more problems with soft-bodied invaders because many of the chemical toxins used for significant pests kill the good guys that would otherwise checkmate foliar feeders, thus increasing these sorts of problems dramatically. It’s far simpler to count on natural dynamics like predator mites to get the job done. You can pinch aphid infestations off terminal shoots on young trees if necessary, or shut own the ant highway by applying sticky goo to plastic wrap on the trunk. If a certain plum variety appears overwhelmed by honeydew secretions from aphids and thus accompanying sooty molds cover most of the canopy, I rely on pure neem oil applications (made at a 0.5 percent concentration every four to seven days) on that particular tree while an especially severe problem persists. Wooly, rosy, or plan green…aphids do not like neem. Leafminers (the larvae of a small moth) tunnel into the cellular layers of the leaf to feed, but you will rarely see much of this damage in a home orchard because certain braconid wasps know their duty. That’s the rub in a sense…we actually need low number of foliar feeder populations to maintain helpful species to a sufficient degree to keep those same foliar feeders in balance.