Bramble On: The Ins and Outs of Growing Raspberries

Fresh, ripe raspberries picked straight from the garden in the morning.

What could be a better start to your day?

According to Michael Phillips, author of The Holistic Orchard, growing your own berries is entirely possible for anyone with a bit of space and a passion for the fruit. Brambles grow from the north to the south and are easy to get started, requiring little more than a patch of sun and well-drained soil. What’s more, berries are highly perishable and often pricey, thus making growing your own a desirable option for obtaining the fruit.

The following is an excerpt from The Holistic Orchard by Michael Phillips. It has been adapted for the web.

(Autumn Britten produces a fall crop on first-year canes. Given proper pruning, those same canes make a comeback to produce more berries early on the following summer. Photo courtesy of Backyard Berry Plants.)

Background on Brambles

Both red raspberry and black raspberry are somewhat insistent about home turf. Reds like summer on the cooler side, while blackcaps can take far more heat. Winter hardiness follows accordingly—red raspberry can certainly tolerate –20°F (–29°C), whereas black raspberries start to take a serious hit at –5°F (–21°C). All share chilling requirements ranging from eight hundred to sixteen hundred hours, meaning neither is going to venture too far south. That’s a niche well filled by blackberry.

Cane terminology is required to further distinguish bramble considerations. First-year canes are called primocanes. These arise from ground level each spring and grow vigorously. Shorter day length and cooler temperatures in early fall signal summer-bearing red raspberries, black raspberries, and blackberries to initiate flower buds. The following spring, the second-year canes will fruit starting in early summer and then die off after the harvest is done. These so-called floricanes define traditional bramble culture. Fall-bearing red raspberries, however, do this complete cycle in a single year. Once a certain number of nodes of growth are reached (genetically predetermined by variety), the fall-bearing primocane initiates flower buds from the tip of the cane downward. These then bloom and fruit, with the fruit typically ripening in early fall. Different pruning scenarios follow from here, including being able to mow down a fall-bearing patch annually and thereby ensure winter survival.

Management of brambles cues to where new canes arise. Red raspberries reproduce asexually via underground runners. These pop up and renew bed potential in a narrow hedgerow. Black raspberries rarely send out runners, preferring instead to tip-root where the growing point hits the ground. Head such canes back and you have the makings of an excellent containment plan. Black raspberries initiate new canes from the crown of the plant rather than from root suckers. Accordingly, cultivars are grown in a hill system where each plant is grown independently, with pruning done on a per-plant basis. These require summer tipping—unlike red raspberries—because individual canes would otherwise grow to unmanageable lengths.

Planting Specifics

With all that firmly in mind, let’s get to planting.

Amateur fruit breeder Pete Tallman in Colorado has his eyes set on a primocane- bearing black raspberry with good flavor and size that proves hardy through- out Zone 5. These berries from one of his recent improved selections show he’s making progress! Photo courtesy of Pete Tallman.

Red raspberries are typically planted 2–3 feet apart within the row, knowing that many new shoots will originate from root buds. Black raspberry plants do not spread far from the original plant and hence do not fill in the row in the same manner as red raspberries. That said, considerable space is needed for each plant because they produce new canes from the crown area, as well as strong lateral branches when pruned properly. Plant black raspberries about 3–4 feet apart within the row, and plant the more vigorous purple raspberries 5–6 feet apart in the row.

Incorporating woodsy compost into the planting bed suits all brambles. Studies in Switzerland have shown that compost made from green material and wood chips produced the best results for nutrient availability and aeration around the roots, and the highest levels of beneficial fungi. Spread compost 2–4 inches thick across a 2-foot width down the length of the intended bed. Keep a steady hand on the tiller at this late stage of the game . . . ideally by keeping this bacterial machine at a distance! Lightly forking the compost into the soil instead will maximize the fungal advantage provided by a red clover crop sown the season prior to planting.

Red raspberries and blackberries can asymptomatically (showing no outward sign themselves) carry viruses that severely affect black raspberries. Nurseries typically recommend that these bramble types be kept 100 feet apart, whether cultivated or wild. These viruses are spread by aphids and windblown pollen. Black raspberries will do fine at first but can quickly decline after a mere three to five years. The stated isolation distance, in truth, doesn’t really alter eventual realty. Regional recommendations take this into account. Great strides are being made in discovering new sources of aphid and disease resistance in black raspberry germplasm, so hang tight.

Raspberry Varieties to Consider

I grew up loving wild black raspberries in southeastern Pennsylvania. Yet here in northern New Hampshire, hardiness alone rules out that choice (though I did try). The abandon with which red raspberry fills in openings in the woods across northern zones tells all. On the other hand, heat, drought, and yet other viruses are issues for red raspberries in the Southeast. Growers in maritime climates need to consider other parameters yet again in deciding which cultivars will make the grade in the long run. The best berry choices for each region are about far more than flavor preferences.

Some people find red raspberries boring—tart and with a small bit of flavor compared with the complexity of the black raspberry. Tellingly, that’s a southern friend speaking. Black raspberries are a heat-loving crop. These brambles winter-kill to the snow line if temperatures drop to −5°F (–21°C) in combination with dry winds.2 Red raspberries, on the other hand, love cooler days and nights. Come farther north and you will be pleased by their full potential.

Fall-bearing red raspberries go a long way toward addressing disease frustrations in viral pockets. Summer bearers in such places tend to burn out in five to seven years. The strategic advantage offered by fall varieties has to do with a later bloom time: Wild summer bearers proffer virus-laden pollen in spring, yet this vector is long gone when fruiting primocane types (maintained by annual mowing) flower in midsummer. Growers in the Pacific Northwest report red raspberry success with Heritage (the very first of the fall bearers) going on twenty-five years now, when grown in rich soil with a touch of dappled shade. Other advantages follow here: cooler picking conditions, far less berry mold, and a fuller sweetness in the fruit itself in the drier fall window.

The banana overtones of Anne add to the surprise of encountering a yellow raspberry. Photo courtesy of Backyard Berry Plants.

The raspberry spectrum doesn’t end with a mere two colors, of course. Purple raspberries are the offspring of a red and a black raspberry and exhibit characteristics of both. Royalty is an excellent purple, producing good-sized berries that shine when made into jam or an ice cream topping. The gold raspberry lost the ability to make red color anthocyanins in its breeding. Anne is the largest and best-tasting (with banana overtones, no less) of these pale yellow cultivars. It grows well in middle zones—provided the viral challenge doesn’t do in the patch in too quick a time—and ripens in fall if managed as a primocane bearer. These many-hued variations of raspberry run on the mild side flavor-wise compared with their darker compatriots, but they sure do liven up the fruit bowl with unexpected color.

Allen. Bristol × Cumberland. Large, firm, juicy, very sweet, glossy black berries. Consistently productive. Uniform ripening, so harvest period is short. Disease-free. Widely adapted summer bearer. Developed at the New York Experiment Station. Ripens in early July. Zones 4–8.

Autumn Britten. Red everbearer from Great Britain. Bears fruit from late August through the fall, followed by early-summer production if properly pruned. Firm, coherent berry with good flavor. Winter-hardy to –20°F (–29°C). Will produce in warmer climates with limited winter chilling. Zones 4–8.

Black Hawk. Very large, nearly round black raspberries. Flavor of a rich Merlot wine. Exceptional quality. Does not crumble, even when a little overripe. Bears despite hot, dry weather. Resistance to anthracnose. Ripens late midseason on second-year laterals, with a picking window of two weeks. Introduced by Iowa State University in 1955. Zones 5–9.

Boyne. Summer-bearing. Consistently produces deep red berries with an aromatic, sweet flavor. Strong canes. Spreads quickly by suckers. Extremely winter-hardy. No disease issues. Hardy to Zone 3.

Caroline. Most productive primocane bearer. Ups the taste parameters for a red raspberry with a rich intensity. Success in many soil types and locations. More tolerance for root rot than Heritage. Does not tolerate high heat or drought. Ripens earlier in fall, thereby escaping late frosts. Zones 4–7.

Heritage. Most resilient primocane bearer. Drought-tolerant, outcompetes weeds, long-lived. Decent-sized berries. Moderately productive. Requires a long ripening season, otherwise frost gets fruit. Prone to die if it has wet feet. Best in Zones 5–7.

Jewel. Black raspberry with rich, jammy flavor. Very noticeable seeds and thorns. Canes grow up to 10 feet. Tip-roots very easily. Best choice for the Appalachians and Midwest. Hardy to –15°F (–26°C). Best in Zones 5–8.

Killarney. Bright red fruit. Good raspberry flavor and aroma. Ripens in midsummer. Upright, bendy canes require trellis support. Modest suckering. Released in Manitoba in 1961. Extremely winter-hardy throughout Zone 4.

Polana. Annual fall bearer. Heavy producer of ruby-red fruits that tend to be favorites among berry lovers who prefer a tart counterpoint to plentiful fruit sugars. Ripens three weeks earlier than Heritage, allowing northern growers to beat the frost to the harvest. Vigorous yet relatively short canes. A side-dressing of compost or protein meal in late spring is advised. Zones 3–8.

Prelude. Red everbearer that bears heavily in its second year in June (if stimulated with proper pruning). A lighter fall crop from first-year canes begins the split-crop cycle. Very large, firm fruit. Well adapted to the Coastal Plain and Piedmont. From Cornell Small Fruit Breeding Program. Zones 4–8.

Taylor. Awesome late-summer raspberry. Considered the best-flavored red variety you can grow. Medium-colored, medium to large, long-conic berry. Subject to mosaic virus (aphid vector). Sturdy canes need no support. Introduced in 1935. Zones 4–8.

Pruning Tips for Raspberries

Cane fruits are biennial by nature, completing the fruit cycle in two years. The crowns are perennial with respect to sending up new canes from buds at the crown each spring. Early in the fall, summer-bearing red raspberries initiate lateral buds at the base of leaf nodes on the primocane. Early in the second season, short fruit-bearing laterals grow from these buds. After fruiting, the old canes die, leaving the bed to the vigorous canes that grew all summer. Call this scenario number one.

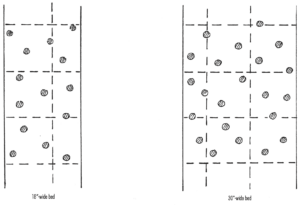

Light enhances growth; ergo, favor stronger canes and thin out the rest. Cane density should amount to two or three canes per square foot across the width of the bed. Illustration by Elayne Sears.

Back at the midpoint of the last century, breeders made use of a wild raspberry strain that fruited in its first year. Initially, results were meager—small fruit with an abundance of seeds, yet ripening from late August on first-year canes. This introduced the advantages of later bloom not subject to spring frosts and mowing down the entire planting after every harvest season. Welcome to scenario number two. The modern raspberry revolution arrived with the development of these primocane-bearing cultivars.

One more notion tripped its way into grower consciousness not long after this: Fall bearers become everbearers with proper pruning based on understanding the fruiting primocane. The top third to half of the cane fruits in year one, but the portion below reserves its fruiting potential for the second year. That sets up scenario number three for certain varieties that yield particularly well from a split-crop production approach.

Summer-bearing red raspberries, black raspberries, and purple raspberries are pruned to increase production and bed longevity. Many growers do this entirely in the dormant season (immediately following snowmelt in early spring). Others tip canes considerably lower—or maybe not at all—depending on the vigor of the variety. Black raspberries should be summer-topped to encourage stouter growth. This plan espoused by Nourse Farms especially suits the traditional red raspberry:

- The spent fruiting canes are removed soon after harvest. They should be cut off close to the base of the plant, removed from the planting, and destroyed.5 Good air circulation helps reduce disease pressure on first-year canes.

- Selecting the more vigorous canes to keep has merit at this point in late summer. Production potential increases for the next season by letting more sunshine in for lateral bud initiation in fall. Thin to leave canes ½ inch or more in diameter (by removing weaker live canes) on a square-footage basis of two or three canes across the width of the bed.

- Once the canes have seen a few killing frosts, summer red raspberries are topped at 6 inches above the trellis wire. Having a top wire at 54 inches above the soil means the canes are being pruned at 5 feet tall for the winter ahead. The fall laterals on black raspberries are cut back to 12 inches at this same time. This trim in late fall results in the virtual elimination of winter damage.

Two crops a year can be picked from the same raspberry planting. Allowing a fall bearer such as Prelude to crop again keys to the ability of the lower part of the cane to fruit that second season. Illustration curtesy of Elayne Sears.

Primocane-fruiting red raspberries are cut to ground level after the harvest in fall. A heavy brush mower gets the job done, or you can use a pair of loppers to cut canes down individually. One-inch-diameter canes will probably prove too much for a lawn mower. Winter hardiness issues become a moot point when cane survival rests in the crown. The row can be narrowed to 16–18 inches wide at this time by tilling. Mulching the bed edges heavily with cardboard covered with ramial wood chips is a biological alternative . . . with a light dressing of wood chips in the cane area as well to help limit weeds the following season.

And that brings us to red raspberry scenario number three. Every primocane bearer can theoretically be managed for split-crop production if a grower so chooses. Prelude should definitely be held to the everbearer pruning plan, as its berry production the following June dwarfs a lesser fall crop. Home orchardists with limited space find this the way to go, being able to count on a couple of handfuls of berries every few days in early summer as well as through the fall from a single planting.

- During the winter or early spring, prune the standing canes at about chest height (about 4 feet high). Multiple fruiting laterals or additional cane development from the top auxiliary buds will result. Basically, this cut removes the top portion of the cane that produced fruit the fall before and initiates lateral branching on the remaining portion of the second-year cane that remains.

- A new batch of primocanes that will produce the next fall crop will grow in the meantime. The net result is two crops in the same year from two different sets of canes. Bed crowding occurs to some extent—so be sure to remove the June-bearing canes when the early fruiting cycle ends.