Presenting the Four-Season Harvest

For most gardeners, a typical season begins with planting in the spring and ends with a big harvest in the fall – one that the frugal home-gardener hopes lasts through until spring sprouts again. And if it doesn’t, well, then it’s off to the store to pick up whatever measly, unfresh produce is available. But it doesn’t have to be that way. With some planning, patience, and a little expert advice you can be enjoying a year-round harvest without any added work. Don’t believe us? Take it from organic gardening pioneer, Eliot Coleman.

The following is an excerpt from Four-Season Harvest by Eliot Coleman. It has been adapted for the web.

We are long-time devotes of four-season food production and, to tell the truth, we haven’t been doing too badly making use of both winter and summer sunshine. We do this because we love to eat good food and share it with our friends. Our four-season harvest is based on a simple premise. Whereas the growing season may be chiefly limited to the warmer months, the harvest season has no such limits. We enjoy a year-round harvest by following two practices: succession planting and crop protection. Succession planting means sowing vegetables more than once. Sowings at one- to three-week intervals during the growing season will extend the fresh harvest of summer crops for as long as possible. Midsummer to late-summer sowings of hardy crops begin the transition to the cool months. That is where crop protection takes over.

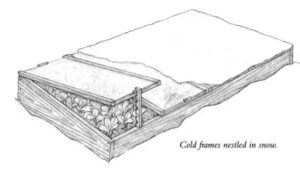

Crop protection means vegetables under cover. The traditional winter vegetables are very hardy. They will survive the fiercest cold under a blanket of snow. Since we can’t count on snow cover, we substitute simple protective structures such as cold frames and plastic-covered tunnels. Many delicious winter vegetables need only this minimal protection to yield through the winter. All it takes are seeds of some familiar and unfamiliar hardy vegetables, a little crop protection, and a dose of innovative thinking.

Crop protection means vegetables under cover. The traditional winter vegetables are very hardy. They will survive the fiercest cold under a blanket of snow. Since we can’t count on snow cover, we substitute simple protective structures such as cold frames and plastic-covered tunnels. Many delicious winter vegetables need only this minimal protection to yield through the winter. All it takes are seeds of some familiar and unfamiliar hardy vegetables, a little crop protection, and a dose of innovative thinking.

The innovative thinking involves realizing that only the harvest-season, and not the growing season, needs to be extended. The distinction is important because the harvest season can be extended with cool-weather vegetables and simple crop protection. Extending the growing season, however, involves adding or collecting heat, storing heat, adding insulation to protect that heat, and providing extra lighting for long-day summer crops. Growing-season extension is highly technological. Harvest-season extension is basically biological. It is also just plain logical. The harvest is what you eat.

We prefer not to define our simple crop protection method as “unheated,” because that makes it sound as if we are not doing something—heating—that we should be doing. The reason our protection is unheated is because heating is not necessary. We often avoid the word “greenhouse” since many people assume that a greenhouse, if unheated, is a super-insulated technological marvel or a complicated heat-storage device. Ours is neither. The best short statement to describe our approach to the four-season garden is a quote from Buckminster Fuller in his book Shelter (1932): “Don’t fight forces; use them.” Instead of bemoaning the forces of winter and trying to fight them by adding heat, we have limited our intervention to the climatic protection provided by one or two translucent layers. Instead of trying to grow heat-loving crops during cold weather, we have said, “So it’s cold, great! What likes cold?” The answer is some thirty or more hardy vegetables.

Fighting force requires energy, and energy costs money. Our approach is to take advantage of everything that a translucent layer can get for free from the sun and the residual heat of the soil mass. In our minds, we have created an inexpensive “protected microclimate” and then found the plants that will thrive in that microclimate. The same applies in reverse during the summer. When those protected microclimates are extra warm, we don’t fight that warmth with motorized greenhouse cooling systems. We use it to grow heat-loving crops.

Fresh harvesting all year round makes life simpler and easier in a number of ways. Since most of the fall, winter, and spring crops are planted in midsummer to late summer in spaces vacated by summer crops, this system results in year-round eating without year-round gardening. By extending the harvest, you also spread out the work. All the planting doesn’t have to be done at once in the spring, and all the harvesting isn’t crowded into the late summer.

Instead of being a series of chores (putting in the garden, weeding the garden, harvesting, and canning and freezing) with rather rigid time frames, home food production becomes a part of the whole year. The four-season gardener doesn’t have a date, such as Memorial Day (traditional in New England), to put in the garden. That’s because there is no goal called “putting in the garden.” The garden is in all the time. The goal is to eat well.

Is this more time-consuming? Not at all. It is certainly more pleasurable. The four-season harvest is a different arrangement of time and a different appreciation of the importance of quality food. It will free you from the chores of food preservation and trips to the market. You will always have fresh food in the garden—crisp and delicious. You will have set up a system that features many different vegetables in their respective seasons rather than a limited list of vegetables suitable only for the summer season. The amount of work comes out about the same over the course of the year. The benefits are that the joys of a fresh harvest continue through all four seasons and the food is more nutritious and varied.

If this is such a great concept, why isn’t everyone doing it?

One reason could be that in many people’s minds, the idea of supplying most of their food seems like a large, complicated chore outside of their experience. But the truth is that growing food is the most basic activity of human civilization, not some mysterious industrial process. You do not need a large-scale operation. Your food is not produced in bits and pieces around the year. You are integrating the garden into your life the same way you integrate other important activities, such as helping your children with homework, playing catch and talking with them, sharing household chores, and helping out the neighbors. You don’t hire others to do those jobs. You do them yourself because they are meaningful, joyful, and important to your family’s spiritual welfare. Your food is of no less importance.

The impressive list of benefits from the four-season harvest is what motivates us to encourage others to give it a try. The first benefit is freshness. Nutritionists agree fresh is best and nothing is fresher than the home garden. All the vitamins and all the flavor the food is meant to have are there for you to enjoy. The carrots have crunch, the salad greens have crisp, the spinach is full of life. Week-old salads on the produce shelf can’t compare with those that go from soil to salad bowl on the same day. Good chefs know this, the rare old-fashioned ones who shop the farmers’ markets daily. And gardeners knew it long before the chefs.

The next benefit is variety. We love to eat with the seasons. Just as we have chosen to live in a place where spring, summer, fall, and winter are very different from one another, we like our menu to reflect this. Certain tastes and seasons go together—eating raw peas on the first sweaterless days; roasted corn at a beach picnic; pumpkin pie on a festive fall weekend; endive and mache salad with roasted beets on a day when you’re glad the wood stove is warm. As we have searched for new winter crops, we have been amazed at the wealth of choices.

The third benefit is quality. We are not vegetarians, but we eat a lot of vegetables and salads. They are our favorite foods. We want to know that what we eat has been grown on exceptional soil nourished with all the organic matter and minerals plants need. Since the government bureaucracy has displayed such dismal incompetence protecting us against the dangers of agricultural chemicals, we have decided to make the decisions ourselves. We no longer need to wonder, “Where has this lettuce been and what have they done to it?” Given the impressive statistics showing the nutritional importance of vegetables, we want to get all the minerals, soluble fiber, beta carotene, folic acid, and other positives without any regrets.

The fourth benefit is simplicity. We have been pleasantly surprised at how easy it can be to grow fresh winter food. The first step was to realize that we aren’t gardening in winter, just harvesting. All the gardening was done in late summer and early fall when we planted most of these crops. Furthermore, biology is on our side. The crops that succeed in winter are those that like cool weather. Most fruiting crops such as corn, tomatoes, peppers, cucumbers, or eggplants need the heat of summer to do well.

But the majority of the leafy crops need the cooler conditions of fall-winter-spring if they are to taste good. This is their traditional time of year. Most gardeners know how quickly spinach bolts when warm weather arrives. The same is true for other cool-weather greens: arugula is very sharp-tasting in summer; radicchio and other chicories turn bitter; mache won’t germinate when the soil is too warm or days are long. Cold weather brings out the best in these leafy crops, making them tender and sweet.

Recently many of the traditional European cool-season crops, such as mache, radicchio, Belgian endive, arugula, and dandelion, have been discovered by upscale restauranteurs. There is now a demand to have them available all year. How dull. We look forward to mache and endive in the winter. That is their season, and they are fresh and alive, while corn and beans are limp specimens on the supermarket produce shelf or ice-encrusted in the store’s freezer.