The Ignored History of Nurse PTSD

This article appeared in the September/October 2021 issue of Discover magazine as “Frontline Fatigue.” Become a subscriber for unlimited access to our archive.

In February 1945, U.S. Navy nurse Dorothy Still was a prisoner of war in the Japanese-occupied Philippines. Along with 11 other Navy nurses, Nurse Still provided care for civilian inmates in a prison camp where food was scarce and guards were brutal. Few inmates weighed more than 100 pounds, and most were dying from malnutrition.

On the night of Feb. 22, Nurse Still and the other inmates watched as their captors set up guns around the perimeter of the camp and turned the barrels inward. Other guards dug shallow graves. The inmates had long suspected the camp commander planned to massacre them all, and it seemed the rumors were coming true. Yet Nurse Still and another Navy nurse reported to the infirmary for the night shift. They had little medicine or food to offer their patients; comfort and kindness were all they had left to give.

Nurse Still heard gunfire the next morning at dawn and assumed the massacre had begun. She steeled herself to glance out the infirmary window and saw parachutes gliding to the ground. Liberation had come just in time! U.S. and Filipino forces swiftly evacuated the 2,400 inmates to safety.

But that wasn’t the end of Nurse Still’s journey. She was haunted by the horrors she witnessed in the prison camp, and the trauma stuck with her for the rest of her life. Now nursing leaders and advocates are saying the problem of not addressing nurses’ mental health needs has again reached a critical point. Nurses have been on the front lines of the COVID-19 crisis, but most aren’t receiving comprehensive mental health screening or treatment. Nursing advocacy groups and scholars who study PTSD in nursing warn that leaving nurses’ mental health needs untreated could lead to a nursing shortage, much as it did after World War II.

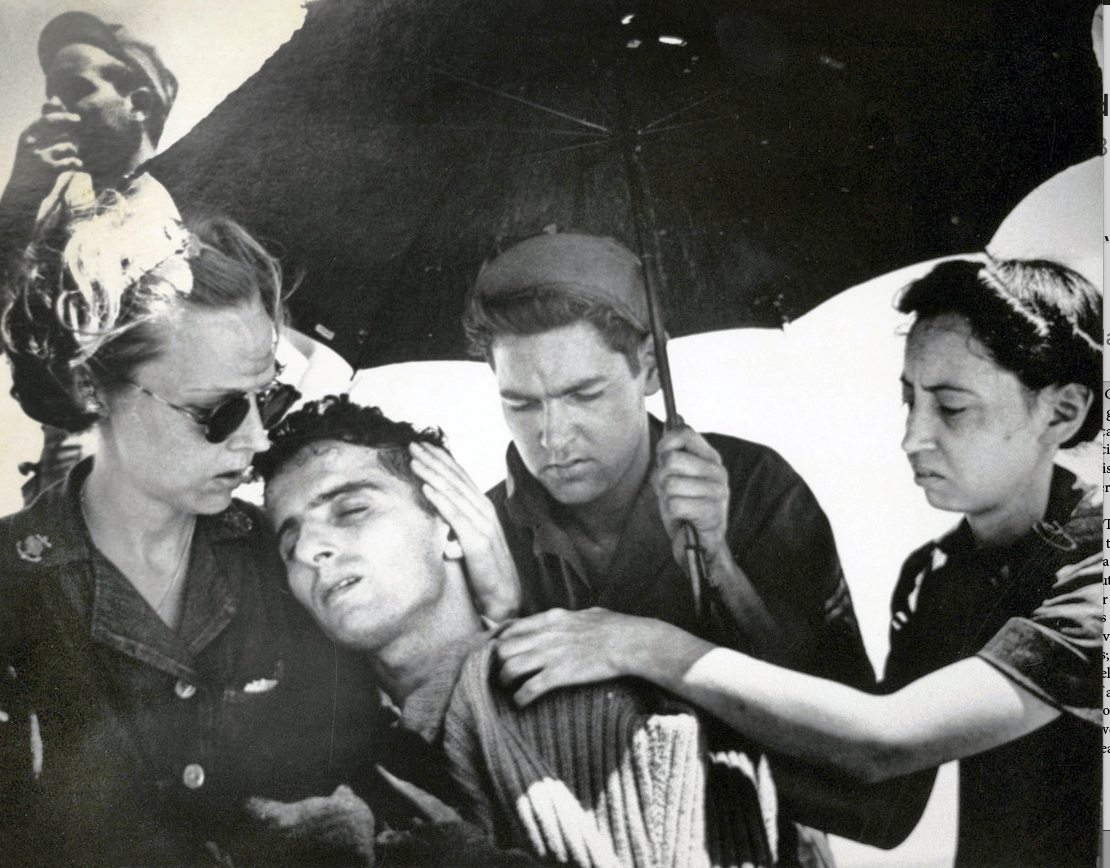

Taken as prisoners of war in 1942, Dorothy Still and 11 other Navy nurses provided medical care in the midst of brutal suffering at Los Baños Internment Camp. (Credit: Courtesy of Bureau of Medicine and Surgery)

Suffering in Silence

Back in the States, Nurse Still was tasked with speaking at war bond drives about the three years she was a prisoner of war. She found the experience troubling and requested a transfer to Panama, but her memories followed her to her new post. At times, she was depressed. Other times, she couldn’t stop thinking about all she had endured. She sometimes cried without provocation and struggled to stop crying once she had started. On advice of her fiancé, she booked an appointment with a naval physician.

During her appointment, Nurse Still told the physician she had been a prisoner of war for more than three years, and asked for a medical discharge based on the trauma she was experiencing. The doctor asked when Nurse Still was liberated; the date was the same as the raising of the flag at Iwo Jima. The physician said those men were heroes, but Nurse Still was a woman and a nurse, and therefore, did not suffer. Denied treatment, Nurse Still left the appointment shaking. She vowed she would keep her pain to herself.

The Navy nurses weren’t the only medical care providers taken prisoner during WWII. Sixty-six U.S. Army nurses as well as hundreds of physicians, pharmacists, and medical assistants were also held captive in the South Pacific. But at the end of the war, as the U.S. prepared to welcome home millions of men and women who served their country, mental health treatment was limited — and reserved for men. Nurses, it was assumed, did not suffer.

At the time, the U.S. military was the largest employer of nurses, and it had established an expected code of silence regarding how nurses responded to their own trauma. In 1947, an article in the American Journal of Psychiatry claimed a military hospital was a controlled environment that insulated nurses from the brutality of war. The study’s author claimed that nurses’ mental health needs were “less complex,” and that nursing fulfilled women by catering to their natural instinct to care for men: “They were supplying a service which gratified the passive needs of men. And which identified these women with the mother, the wife, or the sweetheart back home.”

Many nurses, including Nurse Still, responded to the lack of mental health treatment by leaving both the military and nursing. The late 1940s saw a shortage in nurses at time when hospital admissions rose by 26 percent. The shortage persisted until the late 1960s when wages began to increase.

After three years as POWs, the Navy nurses were liberated in 1945. Here, they speak with Admiral Thomas C. Kinkaid after their release, and are shown next to the aircraft that brought them from the South Pacific to Hawaii. (Credit: U.S. Navy Bureau of Medicine and Surgery)

A Looming Crisis

The COVID-19 pandemic has meant that for the first time since WWII, the vast majority of U.S. nurses are embroiled in fighting a common enemy. It’s a demanding and emotional battle that advocates say adds a deeper stress to an already taxing job.

Across the country, nurses have been caring for patients dying from COVID-19 who do not have the support of family at their bedside due to visitor restrictions. “The nurses are often the ones who are serving as the loved one and helping the patient navigate the end-of-life journey,” says Holly Carpenter, a senior policy advisor with the American Nurses Association.

In addition to caring for dying COVID-19 patients, Carpenter says, many nurses were not properly equipped at the height of the pandemic with the personal protection equipment needed to avoid infection. These nurses lived in fear of being infected or transmitting the virus to loved ones at home.

And on top of these stressors, nurses are also still coping with the usual demands of the job. “There are the things that have always been there — long shifts, sometimes mandatory overtime, a workload that’s heavier than you’re comfortable with, having to work through breaks or lunchtime, having to come in early and stay late,” Carpenter says.

Prior to the pandemic, studies estimated that as many as half of critical-care nurses experienced post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Since the pandemic began, researchers have found the crisis has amplified symptoms of mental health problems. A 2020 study in General Hospital Psychiatry found that 64 percent of nurses in a New York City medical center reported experiencing acute stress.

“Acute stress included symptoms like nightmares, inability to stop thinking about COVID-19, and feeling numb, detached, and on guard,” says study leader Marwah Abdalla, a clinical cardiologist and assistant professor of medicine at Columbia University Medical Center. “This is concerning. We know that if these symptoms persist for more than a month, it can lead to PTSD.”

Some nurses experienced PTSD before COVID-19, but the conditions of the pandemic have amplified mental health problems. (Credit: Eldar Nurkovic/Shutterstock)

A person is diagnosed with PTSD if they meet criteria outlined by the DSM-5, the psychiatric profession’s official manual. Criteria include experiencing, witnessing or learning about a traumatic event (such as death, serious injury, or sexual violence); intrusive symptoms like dreams and flashbacks; avoidance of reminders of the event; negative changes in thoughts and moods; and behavioral changes. A person can also develop PTSD if they are repeatedly exposed to details of a traumatic event.

Suffering from undiagnosed or untreated PTSD is a life-altering condition with diverse ramifications, and may lead a nurse to leave health care. “We’re potentially setting up an occupational health care crisis,” Abdalla says. “This has long-term implications for the health care industry and our ability to deliver adequate health care for our patients.”

Carpenter says health care organizations must be proactive with screening nurses for symptoms related to anxiety, depression, and PTSD. Such screenings must be confidential and come with the assurance that a nurse’s license or job will not be compromised. Organizations also need to work to destigmatize mental health diagnosis and treatment.

“Historically, nurses are always looked upon as the healers and the helpers,” Carpenter says. “They feel they need to be strong for other people. What do you do when the hero needs help?”

For Nurse Still, help never came. She left the Navy and nursing, married, and had three children. She returned to nursing in the late 1950s after her husband died suddenly and she needed to support her family.

Only in the 1990s did she begin speaking about her experiences in interviews with oral historians and documentary producers. She also wrote a memoir, but kept the story light and did not disclose her extensive suffering.

The profession has advanced since Nurse Still’s 1940s appeal for mental health support was rejected. “We do recognize the full PTSD, compassion fatigue, and burnout of nurses. It’s been chronicled now and we understand it,” Carpenter says.

Now the challenge is encouraging each nurse to seek and receive help. Otherwise, advocates warn, their health and wellbeing will continue to decline, and history may repeat as stressed nurses leave a strained profession.

Emilie Le Beau Lucchesi is a journalist in the Chicago area and the author of This is Really War: The Incredible True Story of a Navy Nurse POW in the Occupied Philippines.