In Photos: NASA’s Juno Spacecraft Returns Jaw-Dropping Images Of Super-Storms On Jupiter As It Sets Course For Giant Moon

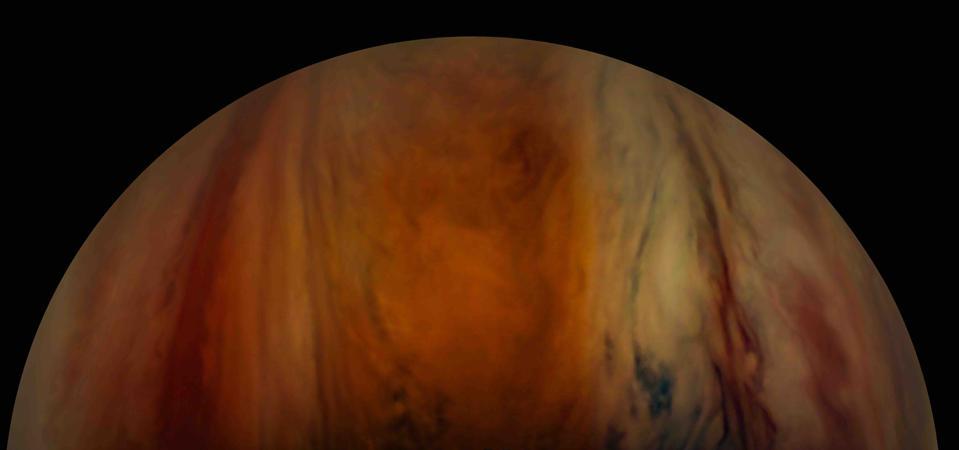

Jupiter’s equatorial zone as taken on Image taken on 15th April 2021.

NASA/SwRI/MSSS/Navaneeth Krishnan S © CC BY

NASA’s $1.1 billion solar-powered spacecraft at Jupiter has completed its 33rd perijove (close flyby) of its main mission at the “giant planet” and sent back another batch of spectacular images across NASA’s Deep Space Network.

The images from Juno’s two megapixel visible light camera—which snaps as it spins—show an incredible storm on Jupiter as well as of the luscious colors of its equatorial belt. It will now slightly alter its orbital path around Jupiter to get a good look at Jupiter’s giant moon Ganymede in June 2021.

Data returns to Earth from the Juno spacecraft after each flyby as raw unprocessed data before being mapped, mashed, blended and enhanced not by NASA, but by an informal team of citizen scientists. They include Kevin M. Gill, Sean Dorán and Gerald Eichstädt, Brian Swift, Rita Najm, Navaneeth Krishnan S and others. It’s their work that you see here—not NASA’s.

Juno had been planned to complete its mission during its 35th and final perijove on July 30, 2021, after which it was due to plunge into the gas planet. However, since the solar-powered explorer is still healthy, a mission extension seemed inevitable, and it was recently granted a second mission to perform close flybys of three of Jupiter’s largest moons.

That effectively sees its inevitable “death dive” postponed for four years during which Juno will orbit Jupiter a further 42 times.

Here’s Juno’s new schedule:

MORE FOR YOU

- Flyby of Ganymede within 600 miles/1,000 km—June 7, 2021.

- Flyby of Europa within 200 miles/320 km—September 29, 2022.

- Flybys of Io within 900 miles/1,500 km—December 30, 2023 and February 3, 2024.

- End of mission—September 2025.

Its new mission will take place as Juno’s elliptical orbits of the planet see it shift further north. As it does so it will get closer to the polar light—aurora—storms visible in Jupiter’s polar regions.

Results in March 2021 from Juno’s Ultraviolet Spectrograph instrument showed for the first time from orbit how those auroral dawn storms are actually born on the nightside of the gas giant, which telescopes on Earth had previously been unable to detect.

This image from NASA’s Juno mission captures the northern hemisphere of Jupiter around the region … [+]

NASA/JPL-Caltech/SwRI/MSSS Image processing by Kevin M. Gill © CC BY

“Observing Jupiter’s aurora from Earth does not allow you to see beyond the limb, into the nightside of Jupiter’s poles,” said Bertrand Bonfond, a researcher from the University of Liège in Belgium and lead author of the study.

Explorations by previous NASA spacecraft at Jupiter—Voyager, Galileo and Cassini on its way to Saturn—were much farther away from the planet and did not fly over the poles.

This view from the JunoCam imager on NASA’s Juno spacecraft shows two storms merging. The two white … [+]

NASA/JPL-Caltech/SwRI/MSSS Image processing by Tanya Oleksuik, © CC BY

“That’s why the Juno data is a real game changer, allowing us a better understanding what is happening on the nightside, where the dawn storms are born,” said Bonfond.

It also recently came to light that Juno witnessed an asteroid or comet slam into Jupiter in April 2020.

A bright flash—almost certainly a meteor hitting the planet—at an altitude of 225 kilometers lasted just 17 milliseconds before disintegrating in its atmosphere.

This illustration depicts ultraviolet polar aurorae on Jupiter and Earth. While the diameter of the … [+]

NASA/JPL-Caltech/SwRI/UVS/STScI/MODIS/WIC/IMAGE/ULiège

That was recorded by Juno, whose very journey to Jupiter between 2011 and 2016 was also recently revealed to have helped scientists solve the mystery of the Solar System’s “zodiacal light.” Its star-trackers sensed cosmic dusk hitting Juno’s solar panels at 10,000 miles/16,000 kilometers per hour.

Juno’s next perijove 34 will be super-exciting; a course correction will reduce its orbital period from 53 days to 43 days and send it on a close flyby of Ganymede—the largest moon in the Solar System.

Wishing you clear skies and wide eyes.