Being Reckless: An Interview with Karl Ove Knausgaard

Read an excerpt from In the Land of the Cyclops here.

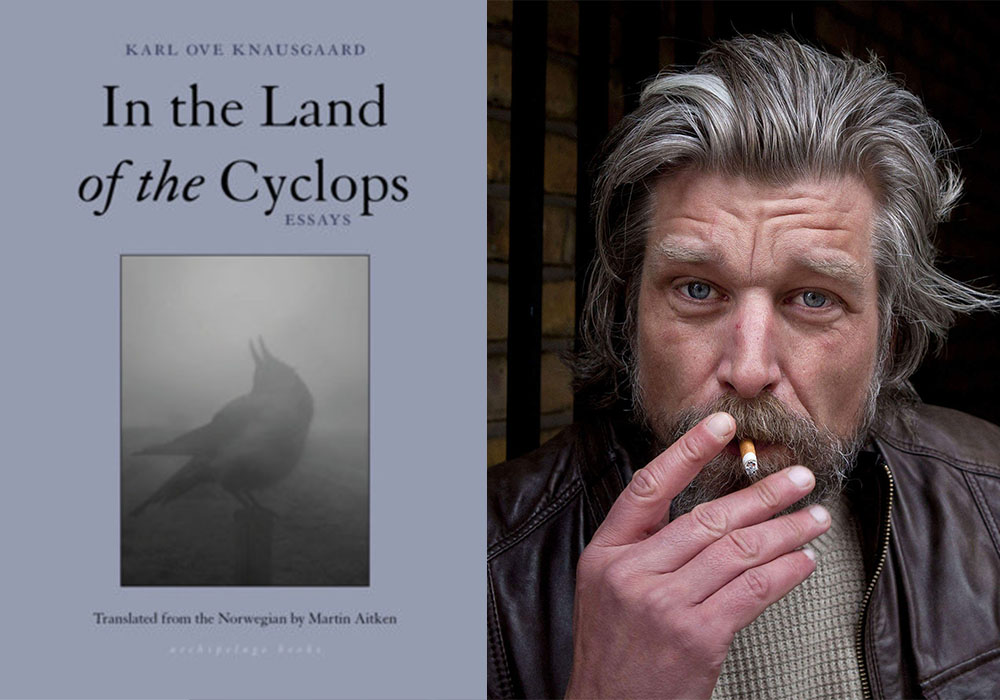

Karl Ove Knausgaard’s newest release, In the Land of the Cyclops, is a collection of essays and reviews translated from the Norwegian by Martin Aitken and published in the United States by Archipelago Books. The title essay, first published in a Swedish newspaper in 2015, is an enraged response to a critic who asserted that Knausgaard’s depiction of a relationship between a teacher and a student in his first novel was pedophiliac. Knausgaard argues forcefully that explorations of all human impulses are necessary, and touches on many of the themes that have lately become associated with his body of work: Nazism—which forms a central plank of Book 6 of My Struggle—identity, literary freedom. While Knausgaard is a writer who is provocative in both the scope and the theme of his work, his politics resist neat categorization: “All my books have been written with a good heart,” as he puts it in this essay, perhaps conveniently. And despite the provocations of its title essay, the book is really a cabinet of Knausgaard’s curiosities. His interests lie in visual art, destabilized reality, meaning, and perception. There are pieces on topics as disparate as the photography of Sally Mann and Cindy Sherman, the perfection of Madame Bovary (“Madame Bovary is the perfect novel, and it is the best novel that has ever been written”), and Knut Hamsun’s Wayfarers. The Bovary essay seems to contain the key to the collection, to the extent that there is one: Knausgaard describes Flaubert’s book as a novel “which is about truth and which asks what reality is.”

About Francesca Woodman’s photographs, which he first dismissed, he changes his view: “Why did I find Francesca Woodman’s photographs, youthful as they were in all their simplicity, so relevant now, while those great paintings of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries suddenly and completely seemed to have lost their relevance to me?” A review of Michel Houellebecq’s Submission, a novel by an author who is a byword for outrage, is about “an entire culture’s enormous loss of meaning, its lack of, or highly depleted, faith.”

The pandemic poses problems for book tours, and Knausgaard, according to his publisher, hates Zoom. We corresponded via email at the dawn of 2021.

INTERVIEWER

The title of your new collection is used as a derisive descriptor for Sweden. Sweden also appears at length in Book 6 of My Struggle, as a figure of scorn for what you describe as its failed, hypocritical social policies. In America, on the Left, there is a fantasy of a sort of single, undifferentiated “Scandinavia” that has wonderful social programs and proves that capitalism can exist along with strong social supports. But during the pandemic, Sweden made choices that did not seem to be in keeping with that reputation. How does the pandemic response align with or recalibrate your ideas about Sweden?

KNAUSGAARD

I would say that there was a certain one-eyedness in Sweden’s approach to the pandemic. They did it their own way without looking to other countries. Even when the death rate in the country was ten times higher than that of the neighboring countries, they continued to do it their way. Having said that, we don’t yet know for sure why some countries have been hit harder by the pandemic than others. But Sweden’s approach wasn’t out of character for sure.

INTERVIEWER

How has the pandemic affected your daily life and movements?

KNAUSGAARD

I have lived full time in London for two and a half years now. Being a writer, I have always worked from home and lived in a kind of permanent lockdown, so the pandemic didn’t change much in that sense. The big difference was that everyone else in the family also stayed home. It worked remarkably well, though; most of the children did online schooling, but it was still a lot of things to do, so I got around four hours a day for writing. Weirdly, I wrote the major part of a novel that spring. I guess that came about because of the time limitation, I couldn’t afford to sit there and think, I had to get the writing moving. The novel was published this fall in Norway. I still can’t get my head around the nature of the pandemic, however, with all the suffering and the horrible number of deaths taking place out there, in the very city we are living in, at the same time as we are indoors, cooking, playing games, and spending more time together as a family than ever before. Somehow, that double perspective found its way into the new novel. It is not about the pandemic, though, but the experience of it must have played a part.

INTERVIEWER

I saw in one interview that you quit smoking, started up again, and then as of 2018 you were back off smoking. What’s your smoking status now?

KNAUSGAARD

Still smoking, unfortunately.

INTERVIEWER

One thing I find interesting about your work is that it is quite often about politics, but your positions on specific matters are usually elusive (“I long to be free, totally free in art … if we look at a picture of a tree, we are immediately caught in a net of politics and morals”). In your essay about Knut Hamsun, you say, “He despises the mass, but not the people who belong to it,” and you, too, seem to privilege the individual rather than the collective. As Jon Baskin points out in his essay about your work, you seem almost to be more suspicious of any feeling of “we” or “us” than of the actual ideas that create that collective feeling (your essay about Anders Breivik in The New Yorker, for example, more or less dismisses his political ideas as a motivating factor in his crime). Have your thoughts on this changed in the last few years, watching the refugee crisis and the response in Europe, or Donald Trump’s election in America? Are the ideas that can unify and animate a group irrelevant?

KNAUSGAARD

This isn’t as easy as your question make it sounds. The one unifying political idea in Europe at the moment is the right-wing usurpation of the we, that is based on the exclusion of immigrants and foreigners. The biggest party in Sweden now is the anti-immigration party, Brexit can be seen as an anti-immigration movement, then you have Hungary and Poland, and Trump came to power with a strong us-and-them rhetoric, didn’t he? The good thing about the Scandinavian welfare state has always been that it has created a feeling that the society belongs to us. They are our hospitals, our schools, our roads and railways, even our politicians. That requires a certain consensus, and that consensus, however necessary, can also lead to exclusion (in Sweden, an exclusion of different opinions, in Norway, an exclusion of the world). So to insist on idiosyncrasy is a way of keeping the “we” open, not closing it down, as your question seems to indicate.

I think that is something all the artists and authors that I write about in In the Land of the Cyclops do. Art is about transgressing the expected, not confirming the world as we know it. Cindy Sherman’s photos are a good example. In some of them she juxtaposes man and woman, flesh and dead matter, fiction and reality, and through that, we can get a glimpse of the boundaries that keep our world together and that we do not normally see, because they are the world to us. Regarding what I have written about Breivik, the essence is actually the opposite of what the question states: the massacre was only possible because of his isolation, the lack of possible corrections, the lack of a real “we.” He operated with a fictitious, or virtual, “we,” in which he was a hero, a defender of Western values. But there was no one else there. He was alone, unavailable for correction. What he did was in my opinion much more related to American school shootings than to political terrorism. In both, there is a lack of belonging, a lack of togetherness, a loneliness. Those pockets of disconnection in society are dangerous, just as extreme polarization is also dangerous. It is created by a lack of hope, a lack of future, a loss of dignity—then another, stronger, simpler identity is taken in their place.

INTERVIEWER

The eponymous essay in this collection was a response to a criticism of depravity leveled at your work. You also write, in the essay “Inexhaustible Precision,” about a critic who, hilariously, positively reviewed your debut, and then retracted the review and wrote a critical one. Is there a response to your work, whether critical or positive, professional or from a lay reader, that has moved you or otherwise stayed with you? I’m curious if, among other things, you hear from readers about your very deft and compelling depictions of parenting. Is there criticism that consistently stings?

KNAUSGAARD

The reviewer who first wrote the novel up and the next week changed his mind and tore it down was unexpectedly honest, and the phenomenon, interesting, not least because I recognized the feeling. I have been mesmerized by books myself, only to find them shallow a few days later, like I have been manipulated. And manipulation is, somehow, a part of the novel-writing trade. At that time, after my first novel, I read everything that was written about me. I googled myself and was very unhealthily absorbed by it all. After my second novel, I stopped doing that. Now I never read anything about my books, neither reviews nor anything else. I learned that from a colleague, Majgull Axelsson. We were on tour together and she probably saw how tormented I was by all the press and then gave me some very good advice: never read reviews. Never read, listen to, or watch interviews, just treat them as nice meetings with interested people and go on. I have done so ever since. To avoid it completely is impossible, however—two days ago, for instance, I bought the Observer at the supermarket here, and when I opened the review pages, I saw my photo and the headline, “Now It Is Our Struggle.” Even if I closed it the next second, I got enough information to understand that it was a review of the essay collection and that it was probably a hatchet job.

But I found the headline funny, and there is nothing I can do about it anyway—the book is already written, and I am working on the next. I don’t know how to make them better, it is never like my writing improves from one book to the next, it is more that the limits are set, and the limits are your personality, the person you are. But improving the writing isn’t my goal, my goal is to make the writing go to new places, to explore things, to search for meaning, to look for the world. It is not about trying to write the one great novel. To me, all writing is the same, be it essays, novels, nonfiction, diaries, or letters. They all have some of that search in them. Of course you can improve technically as a writer, but at the end of the day, who cares about technique? It is a tool, not something to admire in itself.

One of the essays in the book is about Anselm Kiefer’s art, and I was lucky enough to see him work in his studio for a day. It was all process, all about movement, and he was so reckless with his work, which was constantly exposed to chance and arbitrariness. He is incredibly gifted as a visual artist, he can do whatever he wants to, and it was like the material, the matter itself, was a resisting force, something he wrestled with, so that his clever ideas stopped being clever and even stopped being ideas, but became works of art, which is something else. I have been thinking a lot about that since I was there. Edvard Munch was also reckless with his paintings, and incredibly prolific. I do like that a lot, that it isn’t about the one painting or the one book, the one color or the one sentence, but something that goes on and unfolds over years. It is a liberating thought.

So no, I have never learned from critics. But I have always had several readers during writing, the editors, of course, and my wife, Michal, but also friends and colleagues. What happens then is that the book gets more of an objective existence, which makes it easier for me to see it from the outside, what it is, and not only what I want it to be.

INTERVIEWER

What are you working on now?

KNAUSGAARD

This fall, I published a new novel in Norway called The Morning Star. The story didn’t end there, however, so now I’m writing the second novel, and there seems to be a third after that. It is very much fiction, with many different characters and also some supernatural elements in it.

Read an excerpt from In the Land of the Cyclops here.

Lydia Kiesling is author of the novel The Golden State.