The Art of an Even Keel

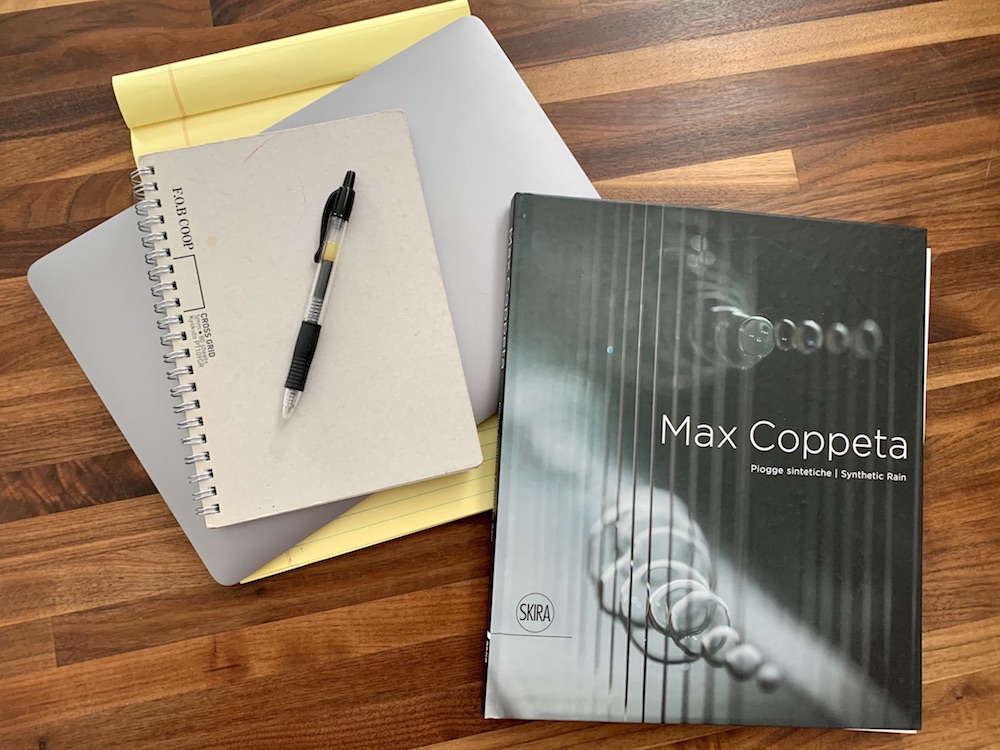

In the torpor of the last ten months, I’ve found myself missing most those things I rarely did before. I miss the grand galleries of art museums, though the nearest are more than an hour away and trips have always been sporadic. I daydream about travel, about the tenuous camaraderie of the airport screening line, the stratus-brushed horizon beyond the window, the world narrowed to a seat, a tray, a book, a bubble of time removed from the world and set ever so gently aside. What I miss, I think, is less action itself than the likelihood of action—or of accident. Even as the pandemic spans four seasons, some underlying transformation (or its potential) is absent; some kinetic possibility is missing in each changeless change. I miss, I want to say, the cusp of things, even as I know this to be a meager complaint amid the litany of real loss. That needling lack remains. And so, seeking some approximation of museum or airport, I’ve turned to the closest thing I have—my shelves—and there found a book on the work of Italian artist Max Coppeta.

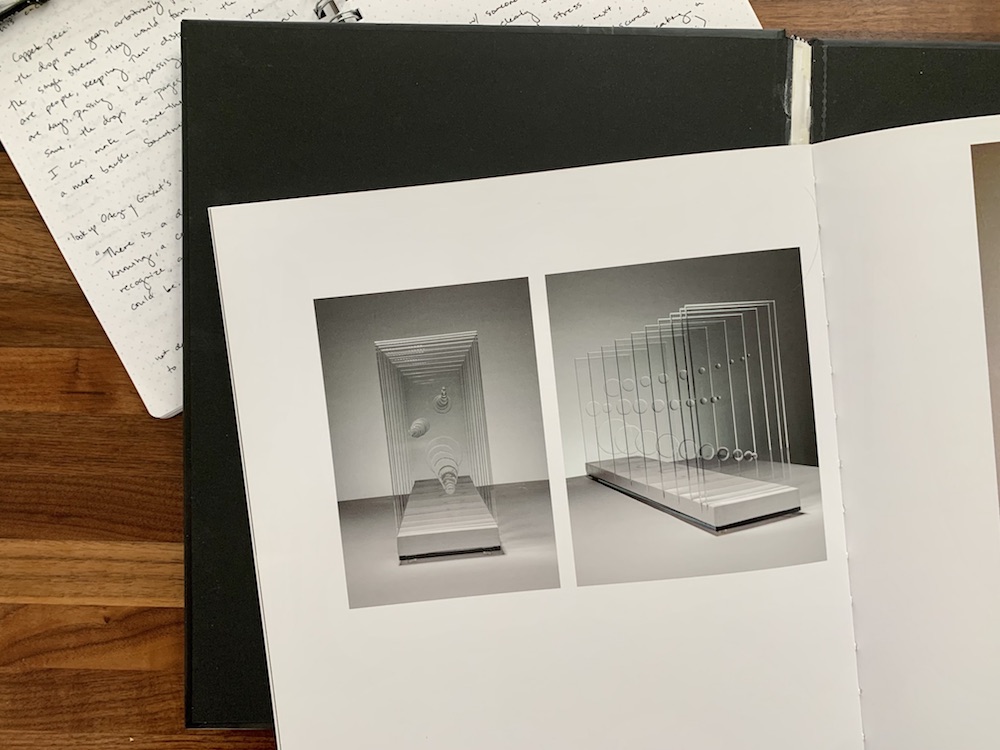

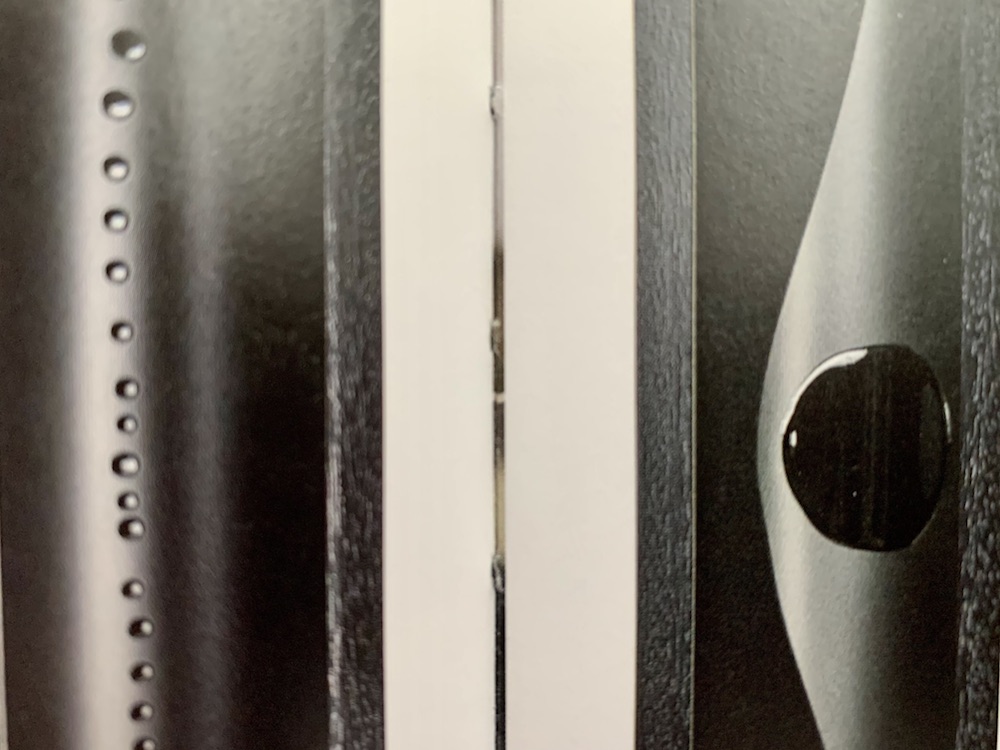

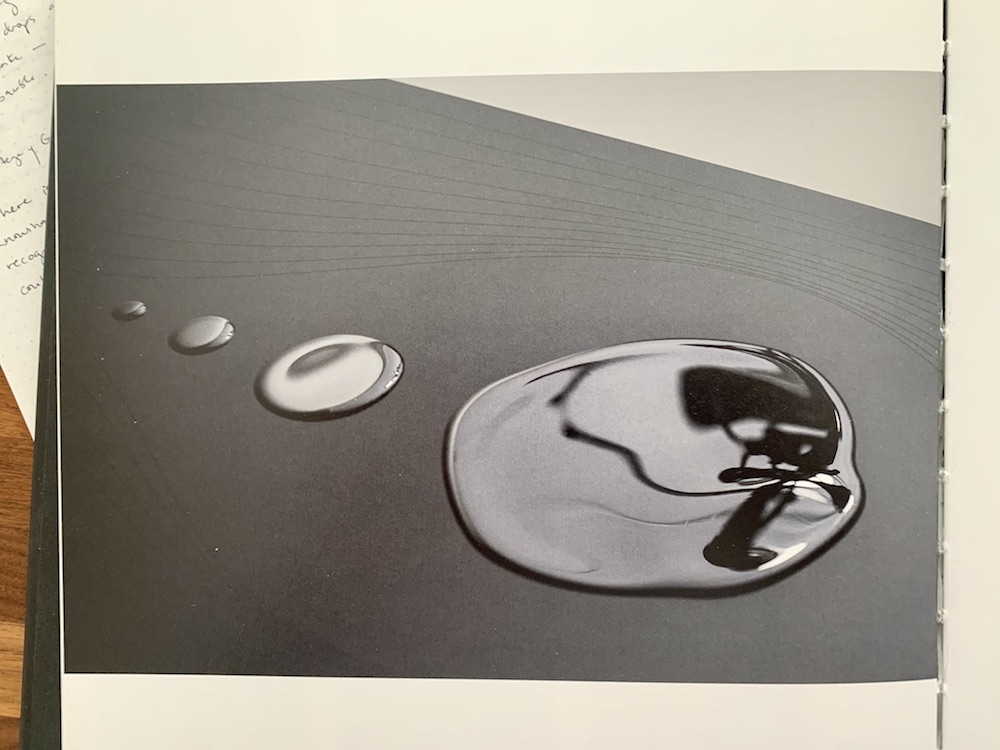

Piogge sintetiche is the book’s title, Synthetic rain, and the unit of measure for the work within is the drop, caught upon vertical or horizontal planes. Coppeta’s synthetic rain is made of crystallized liquid, suspended on sheets of glass, paper, wood, methacrylate, or PVC. Rare is the solitary drop; they come in trios or quartets or scattered crowds. I would call them by the collective noun of patter, flung over a black or bronzed or transparent background or, in certain pieces, spread across a line of upright and parallel planes, one drop to each sheet, as if this rain did not fall but flew, its flight path tracked in glassine intervals like a sleek, modernist update on Muybridge’s birds.

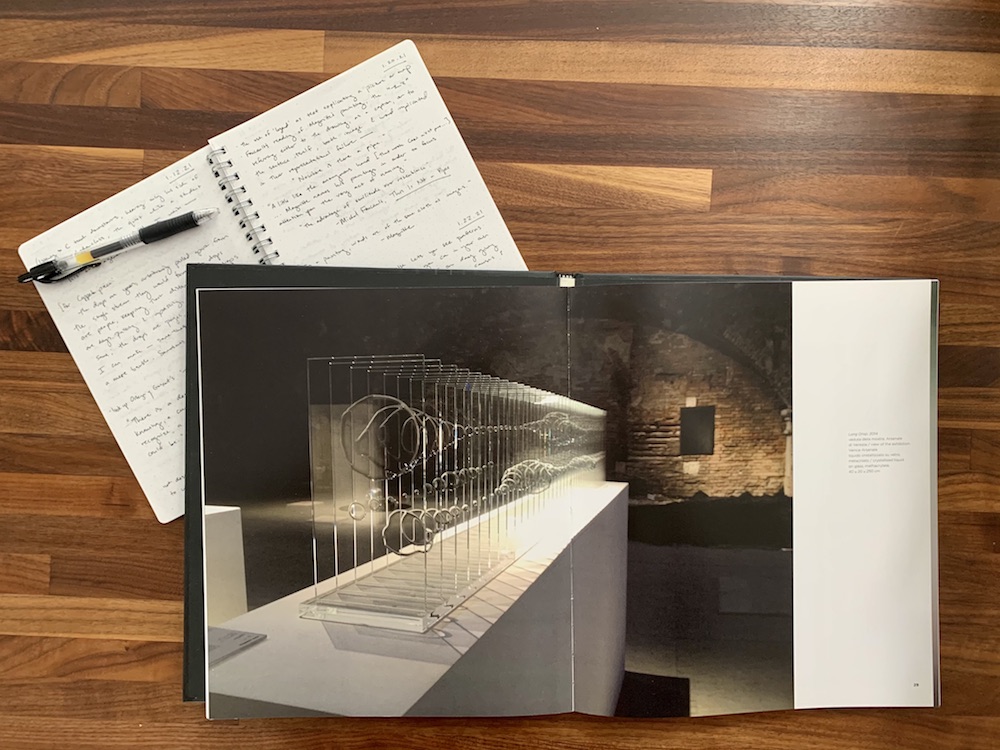

The largest of these pieces is titled Long Drop, singular, though the work is composed of dozens of bubbles of crystallized liquid arrayed the length of a platform, one to each dedicated sheet of glass. The drops look like stuttered steps of the same breath, bubbles spilling from an absent diver’s mouth. My eyes move from one plane to the next as if in order, though they are concurrent. The title gives lie to their separation, to a world in which we expect to see a thing as it is and not as it is, was, and has been, all at the same time. The illusory simplicity of nature—a plain, pretty droplet of rain—gives way to a demonstration of physics, a breakdown of spacetime. Coppeta splits the drop. Like light, carrying the possibility of both particle and wave, his work possesses both sequence and simultaneity, simultaneously. Were you in the same space as this work, you could face it; you could stand at one end of the domino-like line of sculptures and stare it down, nose-to-nose with the flat-headed end of time. Were you in the same space, you could circle it, sidelong.

I am not in the same space. I’ve never seen Coppeta’s work except through the photographs printed in this book. “In a painting, words are of the same cloth as images,” says René Magritte, and in the glossy folds of an artist’s monograph, sculptures are of the same cloth as the words pinned to the page beside them. They are pixels described by other pixels, equally confined, and I lose the thread of my thought in all this representation, every drop doubled in the words written about it—the book’s, my own—like the hall of mirrors at a fairground I wandered through last year—no, the year before last, now. Piogge sintetiche, the cover reminds me every time I turn to it, and I think: Coppeta’s crystallized liquid is rain in the way the word rain is rain—but it’s possible I’ve been reading too much Magritte. It is January in Minnesota, and the only rain I’ve seen in months is this synthetic variation; outside, the snow accumulates.

Coppeta’s pieces, says the critic Antonello Tolve in his accompanying essay, “demonstrate a profound form of ataraxia.” My dictionary defines the word as “peace of mind,” but I read it first in Sarah Bakewell’s biography of Montaigne, and her definition is engraved in my mind, whole and unalterable: “the art of maintaining an even keel.” The word figures greatly in the glossary of my days—I am indisposed to an even keel, often veering too far to one side (depression) or the other (hypomania). Ataraxia, my husband reminds me, for I’ve shared the word with him, when he senses the ship of my mind listing into frenzy; Ataraxia, he says, hands cupped around my shoulders, as if the metaphor might be made literal and my mental state steadied along with my physical form. Funny: there’s no need for such a reminder when I’m tipping instead toward misery—then I try to right myself, desperately, but cannot manage.

For some of October and all of November and much of December, I could not manage.

I bought the book from a small museum in my husband’s hometown, where we visited his parents a few years ago, when we, almost unthinkingly, bought tickets, boarded an airplane, and traveled almost two thousand miles at a speed that could peel asphalt from the earth. The museum hadn’t existed when my husband was a child and teenager, and we were cheered by this sign of someone’s bright commitment to art and thought amid the desert. I bought a reckless number of items (given my small suitcase) from the tiny gift shop, feeling rich in my desire to keep the place there for our next visit. Besides, I wanted to make the unexpected pleasure of the discovery tangible, something I could keep, as we say, for a rainy day. It’s been a rainy day, despite the weather, for ten months now.

The book on Coppeta’s work stood out among the others on display, appealing to certain proclivities: given my pick of an artist’s materials, I would choose glass; given my pick of languages, I would choose Italian, which I spoke every day for three months, once, thirteen years ago, and have never spoken since. In the middle of one delight-filled day, I was reminded of others; far from home, I was reminded of the farthest I’ve ever been. I have always liked to think of happiness as synonymous with travel, with art, although the words are insufficient and the routes are hardly foolproof. Places disappoint, and works, and days—though that one didn’t.

The book’s back cover describes Coppeta’s work as “inviting the viewer to move that which is motionless,” and I think, the spine cracked and pages spread across my lap, of how we speak about freezing time, as if it were liquid—as if the right artist could crystallize it, catching time on a sheet of glass and setting it upright in a gallery. But I’ve been trying to hurry time along, to make it flow or even steam: a physical impossibility, that hastening. I just want to press fast-forward, I’ve said more than once over the last ten months, plaintive and banal, though the days I would set as destination—the summer, the fall, the election, the year’s end—keep arriving, however slowly, and revealing themselves in all their inadequacy. The name of the last year, long used as a blunt epithet for the more subtle devastations taking place, has been exposed as insufficient shorthand. Those devastations persist.

The pages before me hold nothing but their own liquid geometries. Caught upright, the drops threaten to slip, to spill, and never do. They shimmer, whether strewn or aligned in strict formations like diagrams articulating the complex principles of what, I do not know. The black or bronzed PVC behind them shines, some secondary illustration of the properties of light, but I like best the series arrayed on clear glass: each drop casts a shadow on the surface behind, a reminder that these barely-there suspensions have heft, and can cause interruption. Coppeta’s background is in set design, a profession concerned with building the world in a few square feet, and I find new rules of nature in the simple, impossible properties of each drop: the edge of it static, unspilling, while the gleams and shadows within and around it shift (I imagine) along with the light. Tolve describes light, in Coppeta’s work, “as a totalising ingredient, as a preferred glue between the work and the space, between the fixity of the object and the movement produced.”

I imagine, I had to add, parenthetically, for I don’t know what any light does upon meeting Coppeta’s drops. I realize the foolishness of my fixation, from afar, on these works of art whose appeal lies in their very dimensionality, in their relation to the air around them and the light source above and the viewer standing before, reflected in the glass surrounding the drops to which she’s been drawn or in the liquid drops themselves. My own shadowy outline is precisely what I do not see in these pages; I can see each piece only from the angle chosen by the photographer tasked with its recording, and the gleams of light limning the edges of every drop do not move as I turn the page. We are, both of us, stuck.

Yet I imagine. Perhaps the very lack of my presence there, or the work’s here, is the reason for its pull on me: it requires this imagining. I become an ardent, hard-working collaborator in the museum I struggle to make out of my living room, ignoring the blank gaze of the television and the laundry awaiting folding on the couch. “The cathedral leaves its locale to be received in the studio of a lover of art,” Walter Benjamin wrote. “[T]he choral production, performed in an auditorium or in the open air, resounds in the drawing room.”

It’s not the same, of course. Benjamin said as much, and the difference between the Coppeta pieces I look at and the Coppeta pieces as they are is not unique to these light-strewn sculptures. The aura, as Benjamin called it, of any painted or plastic work is singular and physical and irreplicable. I know this is not how art, any art, is supposed to be encountered, but in this time of limited encounter, I take what I can get. The book is a book, after all, tucked between the writings of John Berger and the notebooks of Leonardo da Vinci on my shelves. I read it as I would read them; I read the photographs of sculptures that are (photographs, sculptures) of the same cloth as the words with which they share the page.

This is not—or not only—a diminishment. Amid the detritus of my own life, rather than within the clean lines of a museum, a sterner corralling of my mind is required—I rise to the task, and am better for it, and feel that I have done something with a day I might otherwise have wasted, as I have wasted so many. Expanse is offered, too, in the way I can make strange musings of these pieces, independent of their reality; there is no chance of being disappointed by the place, the work, or the day, for I have no expectations. Coppeta’s pieces are not large, according to their printed dimensions. But met only in a book, absent the comparison of person or wall, they seem to me massive—life-size, the life provided as metric being my own. I imagine each work stretched to a body’s dimensions, each drop able to be entered like a room. A new room! And myself made new within it.

The binding of the book is separating, a rind of useless glue peeling from the place where the sheaf of pages no longer meets the spine. I’ve worn it out, treated it as roughly as Berger’s essays or Leonardo’s notebook entries, and laid it too flat beneath my hands as they busied with their own notebook and pen. It’s kept me company for the last month, this book, while I write stray lines in its vicinity: For we speak, too, of being frozen in time, as if time were the surrounding glacier, and we the ones who long to melt once more. Lines like that. I’m trying to go easy on myself, you see, to maintain the even keel I have only recently regained. I flip through the untethered pages. I peruse.

The book is bilingual, the concise descriptions beside each piece—material, dimensions, where the work is held—rendered in both English and Italian, the same different words repeated throughout: liquido cristallizzato su vetro / liquid crystallized on glass; collezione privata / private collection. I learn or relearn the words; I learn the gaps between the words. The works themselves are full of similarities and repetitions, cognates and translations of shape and form: drops strung like echoes of other drops, planes reiterated. Even certain titles are repeated: Black Box, 2013; Black Box, 2015. In a series called Pieghe / Folds, pieces of black PVC are creased as if they were sheets of paper that once carried notes. Drops cluster or sprawl along each fold, subject to the small gravities of their making. I like these pieces particularly, for they remind me of the human hand at work in sculptures that otherwise might be nature-made, physical or mathematical, acts of God as much as the rain whose shape they gesture toward. The work of making, too, requires many repetitions, a sameness and sameness and sameness that gives way to something, finally, different.

You sound happier, my mother says over the phone, gently, for she knows how unhappy I can be. Her statement draws my attention to the truth of it; I’ve always found happiness amplified, not diminished, in my own awareness of it, as if reflecting on the state functioned literally—a reflection like that of glass, doubling whatever is placed before it. Liquido cristillizzato su vetro / liquid crystallized on glass. Though this quality is not possessed solely by happiness—depression is a hall of mirrors—and the method is no guarantee. Doubt still comes knocking in the long gray hours of an occasional afternoon, and my teetering mind threatens to undercut, among other things, its own interest in these sculptures, in these photographs of sculptures, in the words I would write about photographs of sculptures and the happiness, yes, I would find there. Why all this bother, doubt wants to know, shutting the broken book. Aren’t they merely trinkets, desk ornaments, distractions fit for a child? Pretty, sure, but not worth this—this elaboration, this reflection upon reflection.

And perhaps I do read too much into them; I read too much into everything. The drops are days, passing and unpassing, unbearably identical; the drops are people, keeping their distance; the drops are pages or sentences or single words, all I can manage—at times, they seem so flimsy, bubble slipping to bauble in my clumsy mind. At times, they catch the light.

Art needn’t be made of glass to offer such reflection. I’m always trying to pinpoint myself in whatever lies before me, as if each work were a map and a spot on it marked, You are here. Without the art, how would I know? The map of my days lately has been circumscribed and small, and still I’ve been unmoored within it, fragile as a page slipped from its binding. I stare at Coppeta’s work, at that profound form of ataraxia, and hope it might inspire the same in me: not peace of mind but activity thereof, a motion made possible by stillness and light. This is another kind of cusp—from Latin’s cuspis, point or apex—neither the end of one thing nor the beginning of another but the balanced and ongoing frisson where they meet. I think of a ship’s prow cutting through the water, steady yet exhilarating. Even-keeled. Afloat. Wind and spray on a sun-warmed face. I think of the endlessly complicated, endlessly beautiful equations that make such a relation possible, that allow a sustained and sustaining equilibrium between the fixity of the object and the movement produced.

Over the phone, a friend tells me that the large art museum where she works as a curator reopened a few months ago, briefly, before closing again. “In the little bit of time that we were open,” she says, “I’ve never seen people looking so slowly. Everyone who was there really wanted to be there.” I’m reminded that I, too, really want to be here. I, too, am trying to look slowly, far from the museums as I am. I don’t mean this sentence as some sort of recompense, some worth found in these days that have cost so many so much. I only mean that this is how I have survived them, how I have wanted to survive.

Mairead Small Staid is a poet, critic, and essayist living in Minnesota.