Source of Mystery Radio Signal Traced to Clash of Magnetic Titans

From across the Milky Way galaxy, something has been sending out signals.

Every two hours or so, a pulse of radio waves ripples through space-time, appearing in data going back years. Now a team of astronomers led by Iris de Ruiter of the University of Sydney has identified the source of this mystery signal – and it’s something we’ve never seen before.

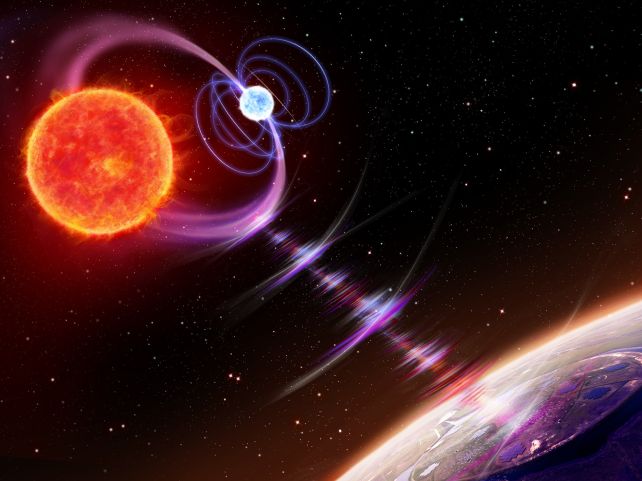

Around 1,645 light-years from Earth sits a binary star system, containing a white dwarf and a red dwarf on such a close orbit that each revolution smacks their magnetic fields together, producing a burst of radio waves our telescopes can detect. This source has been named ILT J110160.52+552119.62 (ILT J1101+5521).

“There are several highly magnetized neutron stars, or magnetars, that are known to exhibit radio pulses with a period of a few seconds,” says astrophysicist Charles Kilpatrick of Northwestern University in the US.

“Some astrophysicists also have argued that sources might emit pulses at regular time intervals because they are spinning, so we only see the radio emission when [the] source is rotated toward us. Now, we know at least some long-period radio transients come from binaries. We hope this motivates radio astronomers to localize new classes of sources that might arise from neutron star or magnetar binaries.”

De Ruiter first discovered the signals in data collected by the LOFAR radio telescope array. Further investigation revealed the earliest detection back in 2015. In some ways, the signal looked like a fast radio burst, a type of powerful blast of radio waves thought to originate from erupting magnetars; but there were some puzzling differences.

Some fast radio bursts do repeat, and some even exhibit periodic patterns. But fast radio bursts are incredibly powerful, detected from up to billions of light-years across space-time. Only one source of fast radio bursts has been confidently identified within the Milky Way galaxy. Fast radio bursts are also, as the name implies, fast: their duration is just milliseconds at most.

The pulses emitted by ILT J1101+5521 came like clockwork, every 125.5 minutes, at lower energies than typically seen for a fast radio burst, and durations that varied but averaged about a minute. The mechanism behind these signals had to be different from fast radio bursts in crucial ways.

Small stars that are far away tend to be faint and hard to see. De Ruiter and her colleagues used the Multiple Mirror Telescope in Arizona and the McDonald Observatory in Texas to home in on the source of the pulses to see if they could identify the object that was creating them.

As you have learnt, there was not one source, but two: a cool, dim red dwarf star, and a much, much tinier white dwarf, the collapsed core of a star similar to the Sun that has lived and died, leaving a tiny dense lump of star stuff behind, shining brightly with residual heat.

These two tiny objects are so close together that their orbital period is just a hair over two hours. The smoking gun was a full, two-hour observation of the red dwarf as it appeared to whip back and forth on the spot – the telltale sign that it was gravitationally entangled with another object, too small and faint to see.

The only known object that would fit is a white dwarf. The two objects are so close together that, with every orbit, their magnetic fields and the plasma therein crash together, producing a burst of radio waves that then propagate through the galaxy.

“It was especially cool to add new pieces to the puzzle,” de Ruiter says. “We worked with experts from all kinds of astronomical disciplines. With different techniques and observations, we got a little closer to the solution step by step.”

It’s the first time that radio pulses have been traced to a binary object. Although they are not fast radio bursts, the discovery suggests that some sources of mystery radio waves in the Universe – including periodic fast radio bursts – may be the product of a binary interaction.

The potential energies emitted by magnetars paired with massive stars, for example, would be much, much higher than the pulses of ILT J1101+5521, which could help explain at least some of the repeating fast radio burst sources scattered across the Universe.

The team plans next to study ILT J1101+5521 in more detail to identify and analyze the properties of the red dwarf star and, by extension, the white dwarf with which it shares its strange orbital dance.

The research has been published in Nature Astronomy.