A Signal of Future Alzheimer’s Could Be Hidden in The Way You Speak

We’re still not sure exactly what causes Alzheimer’s disease, but we know what its effects look like, and we’re getting better at detecting the early signs of it – including, perhaps, those in our speech.

Scientists from Boston University have developed a new AI ( artificial intelligence) algorithm that analyzes the speech patterns of those with mild cognitive impairment (MCI).

It can predict a progression from MCI to Alzheimer’s within six years with an accuracy of 78.5 percent.

The team’s study, published in June, continues their previous research, where they trained a model – using voice recordings from over 1,000 individuals – to accurately detect cognitive impairment.

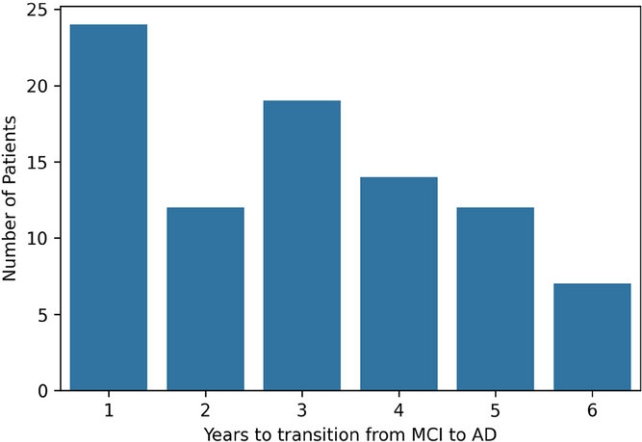

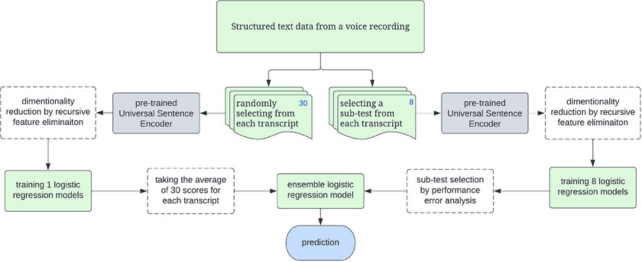

Their new algorithm was trained on transcribed audio recordings of 166 individuals with MCI, aged 63–97.

As the team already knew who had developed Alzheimer’s, a machine learning approach could be used to find signs in their transcribed speech that linked the 90 people whose cognitive function would decline into Alzheimer’s.

Once trained, the algorithm could then be applied in reverse: to try and predict Alzheimer’s risk from transcripts of speech samples it had never processed before.

Other important factors, including age and self-reported sex, were added to produce a final predictive score.

“You can think of the score as the likelihood, the probability, that someone will remain stable or transition to dementia,” says computer scientist Ioannis Paschalidis from Boston University.

“We wanted to predict what would happen in the next six years – and we found we can reasonably make that prediction with relatively good confidence and accuracy. It shows the power of AI.”

Considering there’s currently no cure for Alzheimer’s, you might wonder what the benefit of detecting it early is – but we do have treatments that can help manage Alzheimer’s to some extent, and these can be started earlier.

What’s more, early detection gives us more opportunity to study the disease and its progression, and from there develop a fully effective treatment.

Those known to be likely to develop Alzheimer’s can participate in clinical trials ahead of time.

There’s a lot to like about this approach, if it can be further developed. It’s the sort of test that could be done quickly and inexpensively, even at home, and without any specialist equipment.

It doesn’t need any injections or samples, just a recording, and it could even be run through a smartphone app in the future.

“If you can predict what will happen, you have more of an opportunity and time window to intervene with drugs, and at least try to maintain the stability of the condition and prevent the transition to more severe forms of dementia,” says Paschalidis.

The recordings used here were rather rough and of low quality. With cleaner recordings and data, the algorithm’s accuracy is likely to get even better.

That could lead to a better understanding of how Alzheimer’s affects us in the very early stages – and why it sometimes develops from MCI, and sometimes doesn’t.

“We hope, as everyone does, that there will be more and more Alzheimer’s treatments made available,” says Paschalidis.

The research has been published in Alzheimer’s & Dementia.

An earlier version of this article was published in June 2024.