The Deep Corner

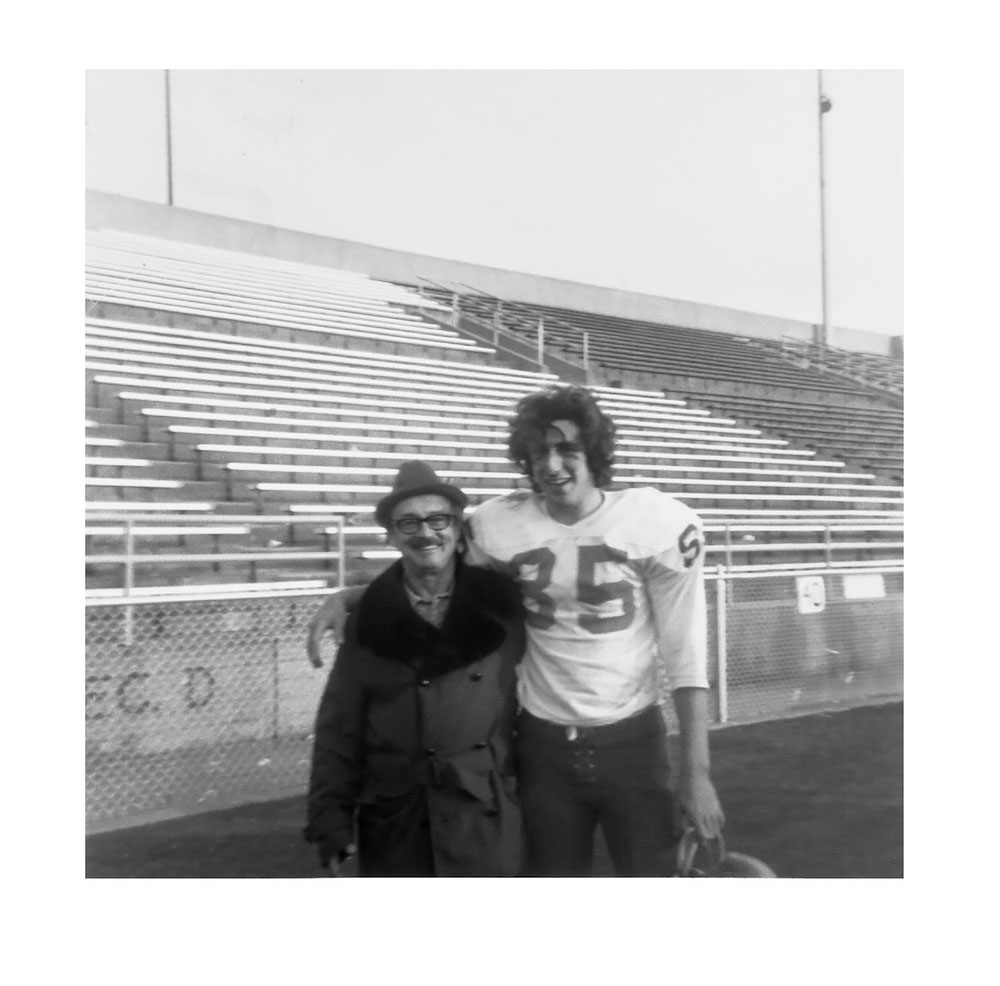

Edward Hirsch with his father before a football game at Grinnell College, 1971. Courtesy of Edward Hirsch.

It has been nearly fifty years since I played college football, but sometimes I still wake up on Saturday with the old feeling. It’s fall, there’s a certain chill in the air, and suddenly I am catapulted back into the bruised light of my dorm room in the early morning, a brisk day dawning in rural Iowa, football weather. I can feel the tingle of anticipation as soon as I open my eyes—a day for running routes and catching passes, blocking down on tackles, hitting, and getting hit.

I was a pass receiver. All night I ran the patterns in my mind until they seemed like second nature: the quick pass over the middle, the sideline or down-and-out, the buttonhook, the post pattern, the fly. The key was getting off the line, feinting the defender—I was quick but not fast and so needed the finesse—cutting on a dime, turning for the ball to come into your hands, holding on afterward. If you touched it, you should catch it—that was the motto I was taught, what I believed. I caught it falling down or stepping out of bounds, I caught it with a linebacker’s helmet planted in my back, I caught it over my left shoulder. I reeled it in with one hand. But I dropped it because I heard footsteps, I dropped it because I took my eye off the ball and looked upfield, I dropped it because I was stretched out and creamed as soon as I touched it. The key was to stay in the moment, to read the defender and keep a Zen-like concentration, run your route with precision. Soft hands. The ball on a string from the quarterback. Keep your head up for the broken play and then improvise, turn, and race down the field while the quarterback looks as if he is going to get sacked. Every now and then he ducks out of it and finds you—you’re floating free. You can see the ball lofting in the air, there is no one else around. Do not take your eyes off it. It takes thirty or forty minutes to come down …

We used to run a trick play called the flea flicker. I was a tight end. I dashed off the line and ran exactly twelve yards, then cut back for the hook pass. As soon I caught the ball, I was pummeled by the safety, but while I was going down my job was to flip it underhand to the halfback, a fleet-footed slip of a guy, who was stealthily following behind. We ran it for touchdowns all through my college career. At the reunion, my teammates were jubilant—Did you see it, they shouted, Boise State ran our play! Our coaches were there, too, and chuckled.

I am not much of a football fan these days. But I loved to play, I loved to be part of the game, the camaraderie of the team, the shared mission. The other day I was washing dishes and my partner pushed me aside—she doesn’t like the way I clean them. Don’t sideline me, I said. It was an old sports metaphor. I never liked being sent to the bench. It has been nearly fifty years, my teammates are old, my coaches are all dead now. But I can still see myself pacing next to Coach on the sideline. He’s watching the defense, listening with one ear. I’m intent on pleading my case. When we get the ball back, Coach, I’ve got this, let’s run the deep corner, they’re not expecting it, I can score.

Edward Hirsch was inducted into the Grinnell College Athletics Hall of Fame in 2018. He has also published ten books of poems, most recently Stranger by Night (2020), and six books of prose about poetry, including 100 Poems to Break Your Heart, which will be published in the spring. His Art of Poetry interview appears in the Winter 2020 issue.